In 16 US states, a supermajority of legislators must agree on any new, or increase in existing taxes. But do such supermajority rules deter state legislatures from increasing taxes on citizens? In new research, Soomi Lee finds that in the short term, supermajority rule reduces the tax burden, but that this effect disappears after about 12 years.

In 16 US states, a supermajority of legislators must agree on any new, or increase in existing taxes. But do such supermajority rules deter state legislatures from increasing taxes on citizens? In new research, Soomi Lee finds that in the short term, supermajority rule reduces the tax burden, but that this effect disappears after about 12 years.

In a democracy, legislators usually need a simple majority of the total votes to approve legislation. In the US, some state constitutions require that new bills to raise taxes require a supermajority vote in both the lower and upper chambers for passage. This constitutional supermajority vote requirement is a procedural limit on the taxing authority of the legislature. It aims to control “the budget-maximizing government” by motivating lawmakers to use existing revenue more efficiently. As of March 2019, 16 US states have adopted the supermajority rule as shown in Table 1. Several others such as Illinois, New Hampshire, New York, and Michigan have tried to adopt one.

Table 1 – States with Constitutional supermajority rules and required votes in both Chambers (as of March 2019)

| State (year) | Provision in State Constitution |

|---|---|

| Arizona (1992) | 2/3 for a net increase in state revenues. |

| Arkansas (1934) | 3/5 for tax rate increase except for alcohol and sales taxes. |

| California (1978) | 2/3 for any change in state statute which results in any taxpayer paying a higher tax. |

| Colorado (1992) | 2/3 for emergency taxes. Emergency property taxes prohibited. |

| Delaware (1980) | 3/5 for imposition and an increase of tax rates and license fees. |

| Florida (1994) | 2/3 for a state revenue increase. |

| Kentucky (2000) | 3/5 for raising revenue or appropriating funds in an odd-numbered year. |

| Louisiana (1974) | 3/4 for the levy of a new tax, an increase in an existing tax, or a repeal of an existing tax exemption. |

| Michigan (1994) | 3/4 for the maximum ad valorem property taxes for school district operation. |

| Mississippi (1970) | 3/5 for revenue bill or any bill for assessment of property for taxation. |

| Missouri (1980) | 2/3 for raising revenue exceeding the revenue limit. |

| Nevada (1996) | 2/3 to create, generate, or increase any public revenue in any form. |

| Oklahoma (1992) | 3/4 for any revenue bill. |

| Oregon (1996) | 3/5 for raising revenue. |

| South Dakota (1978) | 2/3 for any increase or imposition of tax. |

| Washington (1993) | 2/3 for tax raise, fee increase, and new fees. |

Source: Lee (2018)

The supermajority requirement to raise taxes is politically popular because it is deemed an effective way to control “the Leviathan.” But it binds states into a certain way of managing their money, as the political costs such as time, money, and effort needed to come to a consensus among a supermajority are increased. Therefore, adopting a supermajority rule must be based on strong evidence of its effectiveness. Yet previous studies show mixed results on such effectiveness and both supporters and opponents cherry-pick the findings to support their side of the argument. Moreover, practitioners, scholars, and voters make claims that state lawmakers circumvent the rule in various ways, mainly by charging fees instead of taxes. Despite those frequently-made claims, these arguments seem to be based on the implicit assumption that state governments would cheat, rather than based on robust empirical evidence. So, I revisited these questions: how have state governments responded to the rigid rule on legislative taxing authority? Is the supermajority rule effective in constraining tax burden? Do states get around the rule by increasing fees instead of taxes?

Let’s first take a cursory look. I examined states’ tax legislation from 2013 to 2015 using data from the Fiscal Policy Database by the National Conference of State Legislatures. States with the supermajority vote requirement proposed 2.3 fewer bills for a tax increase than states without the requirement. Supermajority states proposed 4.8 tax bills that would bring additional revenues on average, whereas nonsupermajority states proposed 7.1 bills. The lower average number of tax bills among supermajority states seems to suggest that the supermajority rule may suppress tax hikes, but we need a systematic way of assessing the effectiveness of the rule.

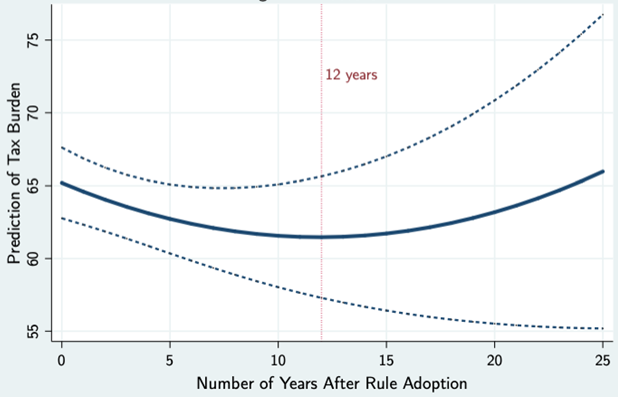

To that end, I used a dataset covering 47 US states between 1960 and 2008. First, I examined the effect of supermajority rules on overall tax burdens – the total state tax payment collected by state governments per $1000 of personal income. Figure 1 shows what I found: the tax burden initially becomes lower as time passes. After about 12 years, however, the tax burden slowly returns to the original level. The U-shaped curve suggests that the effect of the supermajority vote requirement does exist, but it lasts only in the short run, and then eventually fades away.

Figure 1 – Decaying effect of the Supermajority Rule

Note: figure shows predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals

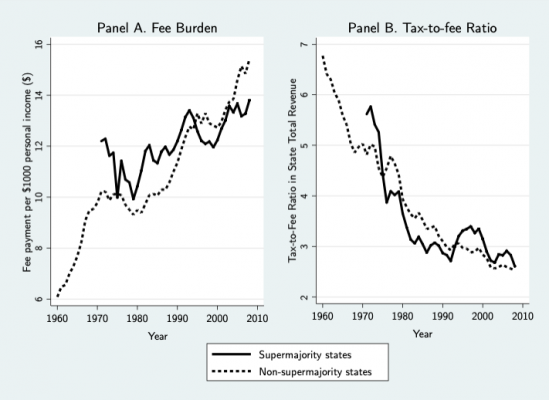

Is the decaying effect of the supermajority rule caused by fee hikes, as claimed in the policy debate? In a nutshell, there is no evidence that states collect more revenues from fees than taxes after the rule adoption. The supermajority rule has no statistically significant effect on fee burdens – measured as the state’s revenue from fees, charges and miscellaneous other sources per $1000 of personal income. In fact, for the last fifty years, all 50 states have increased fees instead of taxes, regardless of the presence or absence of the supermajority rule. Figure 2 illustrates the trends. Panel A demonstrates the upward sloping fee burden, showing that states’ reliance on fees has been substantially and consistently rising in states with and without the rule. Panel B shows that tax-to-fee ratios (revenue raised from taxes divided by revenue raised from fees) have consistently declined since 1960, irrespective of the presence or absence of supermajority rule. Thus, although it is easy to attribute fee hikes to the supermajority rule, my analysis suggest that it is not the contributing factor.

Figure 2 – Trends in taxes and fees in non-supermajority and supermajority states

All in all, the effect of the supermajority rule to discourage a state from raising taxes is short-run at best. In the long run, it is an ineffective policy tool to control “the budget-maximizing government.” So, the verdict on the claims in the policy circle: Yes, it does have an effect on controlling tax burdens, as supporters argue. However, the rule may end up as a symbolic, psychologically pleasing policy with few long-term economic outcomes, as its opponents maintain.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Do States Circumvent Constitutional Supermajority Voting Requirements to Raise Taxes?’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HIJToJ

About the author

Soomi Lee – University of La Verne

Soomi Lee – University of La Verne

Soomi Lee is an associate professor of public administration at the University of La Verne. Her research focuses on state and local public finance and political economy. Her work on effects of budget rules and racial diversity on government finance appeared in State Politics & Policy and Urban Affairs Review.