Last month it was revealed that wealthy American parents paid bribes to ensure their children could attend elite universities and that the British and American Sackler family has sold the pain reliever OxyContin while knowing of its addictive and deleterious qualities. Dan Cohen and Emily Rosenman argue that these two seemingly unrelated scandals illustrate the influence that philanthropy and social finance have over US policymaking. They write that in recent decades philanthropy has moved to a market-focused view, where charitable giving can be directed towards for-profit companies, and towards supporting market-related social policy interventions.

Last month it was revealed that wealthy American parents paid bribes to ensure their children could attend elite universities and that the British and American Sackler family has sold the pain reliever OxyContin while knowing of its addictive and deleterious qualities. Dan Cohen and Emily Rosenman argue that these two seemingly unrelated scandals illustrate the influence that philanthropy and social finance have over US policymaking. They write that in recent decades philanthropy has moved to a market-focused view, where charitable giving can be directed towards for-profit companies, and towards supporting market-related social policy interventions.

In the spring of 2019 the American media devoted extensive coverage to two seemingly unrelated controversies. For several days in March the news cycle was dominated by the stunning details behind a college admissions bribery ring, in which wealthy parents spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to game the system to ensure their children were admitted to elite universities. Meanwhile, a longer-term investigation alleged that the Sacklers, a British and American family that amassed a fortune through manufacturing the pain reliever OxyContin, had marketed this opioid product despite knowledge of – and in fact with an intent to profit from – its highly addictive nature and deadly effects on patients and communities.

While these stories had little to do with one another on their face, their ripple effects highlighted two increasingly influential forces shaping American policymaking: philanthropy and so-called ‘social’ finance. The latter is a type of investing that claims to create both private profits and public benefits, and is increasingly used by both corporate and family philanthropies. Among those implicated in the college admissions scandal was William McGlashan the (now former) CEO of one of the largest social finance funds: the $2 billion Rise fund, created by the private equity group TPG Capital.

As journalist Anand Giridharadas was quick to point out, this meant McGlashan had been privately seeking unfair advantages for his son while running an investment fund that claimed to be (profitably) helping the poor and disadvantaged. Furthermore, the

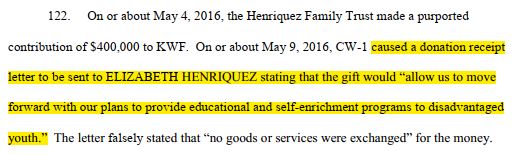

details of the affidavit of accusations (Figure 1) revealed that a non-profit organization was at the heart of the scandal. Tax-deductible ’donations’ to this non-profit, Key Worldwide Foundation, were allegedly used to hide payoffs to college employees and tutors who helped parents and students game the college admissions system. As highlighted below, Key Worldwide laundered the bribes by listing them as tax-exempt donations used to fund “educational and self-enrichment programs to disadvantaged youth.”

Figure 1 – Extract of affidavit of accusations in college admissions bribery case

While the Key Worldwide Foundation case is an extreme example of alleged fraud, scrutiny of the Sacklers’ philanthropic donations raised the question of the connections between elite giving and predatory business practices. Notably, following the allegations, the UK’s National Portrait Gallery and the Tate group of galleries both stated they will no longer accept the Sacklers’ donations.

Less attention has been given to the Sackler family’s ongoing funding of the charter school sector (an American market-based education reform that allows private organizations to receive public money for each student they teach) through the non-profit arm of Jonathan Sackler, the Bouncer Foundation. The Bouncer Foundation has donated millions to charter schools as well as to associated lobby groups and to social finance investors who specialize in charters. This sector has been much less willing to distance itself from the Sackler family. One of the charter chains funded by the Bouncer Foundation told students: “We could say to the Sacklers, we do not want your money. We could. Tomorrow. And as a result, some amount of things that we are able to do here … would go away.”

Photo by Pepi Stojanovski on Unsplash

Philanthropy, profit, and policymaking

In the background of these two scandals involving American elites and charitable donations is a shift in philanthropy over the past several decades towards an increasingly market-focused view of giving. Large-scale philanthropic foundations such as the Gates Foundation now directly fund the activities of for-profit companies, such as Mastercard’s “financial inclusion” programs in Africa, based on the claim that there is nothing incompatible between doing good and profitmaking. In fact, Bill Gates has even argued that for-profit companies can be a better recipient of philanthropic money because of profit incentives, stating that non-profits are less effective because “no one stands to make a profit at the end of the day.” The increased use of what are referred to as ‘Program Related Investments’ (PRI) is one such example, with American philanthropic foundations increasingly making loans or equity investments, rather than grants, to pursue their charitable missions. The claim is that PRIs will “encourage market-driven efficiencies” by making charities operate more like businesses in order to repay loans from philanthropic foundations.

The Sackler family’s grants to charter school lobby groups also highlight how wealthy donors are attempting to shape the direction of American social policy toward market-oriented interventions. The Bouncer Foundation has spent millions funding (and providing seed money for) lobby groups like 50Can and 74million.org, which seek to divert state money from public schools to charter schools, and to fund anti-union legislation seeking to eradicate teacher protections like tenure. Notably, such gifts do not fund initiatives related to student learning.

Such interventions are part of an overall trend towards activist giving amongst elites, in which the state funding of programs has been replaced by the use of so-called philanthropic dollars to advance policy goals. Such funding very rarely comes with any attempt at consultation with those who are impacted by the policy changes sought by billionaires such as the Sackler family. Indeed, this disdain for democratic decision-making was in sharp relief at this year’s Davos summit, with Michael Dell, founder of Dell Technologies, telling the crowd that “I feel much more comfortable with our ability as a private foundation to allocate those funds than I do giving them to the government.” The idea that government social spending is inefficient becomes an explanation for allowing private, untaxed philanthropic giving to drive policy solutions.

Scrutinizing the “continuum” of giving – and the goals of the givers

In the wake of the college admissions scandal, many within the education sector reflected on the thin line between bribing a sports coach to ensure your child is admitted to a university and donating a building to accomplish this same goal. And multiple commentators have highlighted the messy continuum between very high-level giving, which is legal and normalized in American society, and engaging in deception and fraud. Despite the legal and ethical differences between these actions, the underlying mechanism – the buying of influence and advantage – remains the same.

By looking at Key Worldwide Foundation’s role in the college admissions scandal alongside the Sackler family’s (legal) donations of opioid profits to charter schools, we can begin to see how the use of philanthropic dollars to advance policies desired by elites follows a similar continuum. The college admissions scandal is undoubtedly at the extreme edge (fake donations to a fake charity as a means of getting a tax break for bribes). But it draws from a similar logic as social finance and activist modes of philanthropy: attempting to marry financial gain or elite actors’ pet projects – both legal and illegal – with acts that are promoted as providing social goods.

The contradictions of social finance and activist philanthropy often bubble to the surface in market-oriented social policy interventions. For example, the non-profit arm of Pearson Education, the world’s largest for-profit educational services company, was found to have used “charitable assets to benefit their affiliated for-profit corporations” as they partnered with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to push the ‘Common Core’ curriculum on American education despite the opposition of parents and educators. Here the non-profit arm of a for-profit company partnered with one of the largest philanthropic organizations in the world to promote a change to the nation’s education system that was not backed by evidence or public demand, and which would soon fail due to widespread resistance.

This is important is because the philanthropic (or ‘triple bottom line’) interventions of groups like the Sackler family, William McGlashan, and the Gates Foundation are often used to set policy agendas and draw in public funding – and yet, as Michael Dell tellingly revealed, this is done without democratic deliberation or regard for the desires of communities targeted by such initiatives. While the parents in the college admissions scandal are accused of baldly committing fraud as they donated to a non-profit that claimed to be helping disadvantaged youth, donations that push for elite-led projects also use the mechanism of giving to advance the policy goals of elite actors. The US tax system cedes billions of dollars of potential federal revenue to private philanthropy every year, and charitable deductions are overwhelmingly claimed by the very wealthy.

According to the Urban Institute’s Tax Policy Center, only 7.5 percent of households making under $50,000 in 2016 claimed a charitable tax deduction but 88 percent of households making $500,000-$2,000,000 did, as did 94 percent of households making over $10,000,000 that year. As US social policy continues to rely heavily on non-profit organizations and philanthropic donations, and as social finance grows in popularity with investors of all stripes, it is time for increased scrutiny of who stands to win – and lose – from a system built on looking to elite largesse and market logics to set American social policy priorities.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2WOuIOy

About the authors

Dan Cohen – Concordia University

Dan Cohen – Concordia University

Dan Cohen is a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University. His research has focused on the marketization of schooling in the United States and Canada. His current project examines private tutoring markets in Toronto and Montreal.

Emily Rosenman – University of Toronto

Emily Rosenman – University of Toronto

Emily Rosenman is a postdoctoral fellow in the Geography & Planning Department at the University of Toronto. As of July 2019 she is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography at Penn State University. Her research focuses on the intersections between finance, urbanization, and impoverishment in North America.