At the end of March, Maryland’s State Legislature overrode Governor Larry Hogan’s veto of a bill which would raise the state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour. While Hogan argued that the increase would hurt jobs and the economy in Maryland, Liam C. Malloy and Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz disagree. They write that data from other states which have raised minimum wages shows that there is little to no effect on jobs, likely because firms compensate for the increase by having more productive employees, less employee turnover, lower profit levels, and/or passing on their now higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices.

At the end of March, Maryland’s State Legislature overrode Governor Larry Hogan’s veto of a bill which would raise the state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour. While Hogan argued that the increase would hurt jobs and the economy in Maryland, Liam C. Malloy and Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz disagree. They write that data from other states which have raised minimum wages shows that there is little to no effect on jobs, likely because firms compensate for the increase by having more productive employees, less employee turnover, lower profit levels, and/or passing on their now higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices.

Since 2012, several states and cities including California, Massachusetts, New York, and the District of Columbia have voted to gradually raise their minimum wage to $15 an hour. Last month, overriding Governor Hogan’s veto, Maryland joined the ranks of the most progressive minimum wage states and locales in the country.

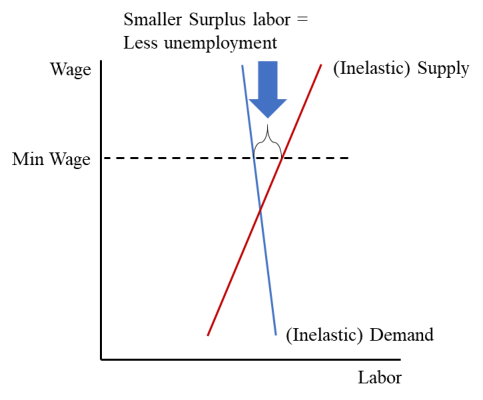

The governor based his veto on the argument that the raise in the minimum wage would harm the state’s economy and drive jobs away. A basic economic supply and demand model of the labor market supports Governor Hogan’s position. When applied to the labor market, this model implies that a higher minimum wage will lead to an increase in the supply of workers, as people are attracted into the labor market, and a decrease in demand for workers as firms decide to hire fewer workers at the higher minimum wage. This price floor, like all price floors, should then lead to a surplus of workers. And in the labor market, a surplus of workers means higher unemployment (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 – Why Doesn’t This Model Work in the Labor Market?

And yet careful empirical work shows that there are little to no negative employment effects when states raise their minimum wage, at least in the short run.

In the absence of significant movements in the federal minimum wage, states started to increase their minimum wages in the 1970s and 1980s as the federal minimum wage failed to keep up with inflation. David Card (now at Berkeley) and the late Alan Kreuger of Princeton University realized that this offered economists a natural experiment in which they could test the effects of a higher minimum wage on state unemployment rates. They first looked at the Philadelphia metropolitan area when New Jersey increased its minimum wage but Pennsylvania did not. The result? There was no evidence that New Jersey’s unemployment rate went up as a result of its minimum wage. This research has been repeated and expanded a number of times and all find little to no effect of higher minimum wages on the unemployment rate with only a few exceptions especially relating to the specific effect of the rising wages for teenagers.

“Jobs Help Wanted” by Innov8social is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

So why could this be? Why does the most basic model in economics, which has a lot of empirical support in other markets, seem to fail when applied to the labor market? One possible explanation is that the demand for (and possibly the supply of) low-wage labor is relatively inelastic in the short run (see Figure 2). Put simply, this means that the amount that firms want to hire is not very responsive to changes in the price of hiring workers. But there are three potential reasons that this demand for labor may be inelastic—all of which suggest it’s because labor is not like other goods and services.

Figure 2 – Is Low-Wage Labor Demand Very Inelastic?

The first, which has been getting a lot of attention from economists recently, is that firms may have a lot of market power in labor markets. As firms get bigger, they can become the dominant or even sole employer in an area and exert monopsony power (monopsony means there’s one buyer, as opposed to monopoly which means one seller). In this case, workers are not being paid as much as they would be in a competitive labor market, and the only effect of a higher minimum wage is a reduction in profits for the business but not actually any job losses. In this case, no jobs are lost; instead an increase in the minimum wage simply makes the lowest paid workers earn more at the expense of the highest paid workers or the stockholders.

The second explanation is that when all firms face higher labor costs, they may be able to pass these costs along to consumers in the form of higher prices. This implies that an increase in the minimum wage will lead to a one-time bump in inflation as prices adjust.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, one last potential reason is that hiring workers is not the same as buying apples. Workers respond to incentives and a higher wage makes a job more valuable. This can lead to lower turnover as workers are less likely to quit, and higher productivity as workers exert more effort to avoid being fired. Both of these effects increase firms’ profits, mitigating or possibly even eliminating, the effect on profits from higher labor costs. In short, a higher minimum wage may actually help employers as they are able to fill unfilled positions and keep employees instead of having to train people just to have them leave a short period later, especially if their competitors are also forced to pay the higher minimum wage.

Each of these explanations show why there has been little empirical evidence supporting short term job losses due to minimum wage increases.

But what about in the long run? As labor costs increase, either because of legislatively mandated minimum wages or simply because of productivity growth, firms may find it in their interests to substitute capital and new technology for labor. In some jobs this may mean that where it used to be profitable to hire a low-wage worker, it no longer is. But that is simply the definition of long-run economic growth: firms search for ways to increase productivity and decrease expenses through technology. And jobs are constantly being destroyed and yet new jobs are created. While this can cause short-run economic pain for some people who find themselves technologically displaced, there is no relationship, in the long run, between higher productivity/wages and the unemployment rate and number of jobs.

In fact, the evidence suggests that a higher minimum wage helps low-income workers and families. A higher state minimum wage appears to increase income and reduce inequality. This suggests that even if there are minor employment effects of a higher minimum wage, they are more than offset by the positive consequences experienced by low-wage workers.

So, who was right? Governor Hogan who argued that the state would experience job losses in the wake of the increase in the minimum wage or the legislature who appears to think that low wage workers will benefit from the increase? At least the literature to date suggests the legislature is more likely to be correct than the governor.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2I1CzVo

About the authors

Liam C. Malloy – University of Rhode Island

Liam C. Malloy – University of Rhode Island

Liam C. Malloy is an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island. His research in behavioral/heterogeneous agent economics focuses on using this developing field to answer macroeconomic and political economy questions.

Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz – University of Rhode Island

Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz – University of Rhode Island

Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz is an associate professor at the University of Rhode Island. Her academic work has been published in the Journal of Politics, the American Journal of Political Science, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, and elsewhere. Prior to entering academia, she worked in state and local government.