Despite policies to counter the legacy of discrimination, such as affirmative action, black students are still far less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree compared to whites. In new research Christina Ciocca Eller and Thomas A. DiPrete find that black students are actually more willing to enter-four year colleges than whites, and that their own actions do at least as much as colleges’ institutional policies to reduce the black-white degree completion gap. Black students’ experiences while in college can also have a huge impact on whether or not they graduate, no matter their pre-college background. To increase the number of black students who do graduate, they write, universities must do more to identify and address the needs of black students.

Despite policies to counter the legacy of discrimination, such as affirmative action, black students are still far less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree compared to whites. In new research Christina Ciocca Eller and Thomas A. DiPrete find that black students are actually more willing to enter-four year colleges than whites, and that their own actions do at least as much as colleges’ institutional policies to reduce the black-white degree completion gap. Black students’ experiences while in college can also have a huge impact on whether or not they graduate, no matter their pre-college background. To increase the number of black students who do graduate, they write, universities must do more to identify and address the needs of black students.

Earning a bachelor’s degree, or BA, is an important step towards achieving the “American Dream.” However, BA completion is starkly unequal. A comparison of the completion rates for white and black students is striking: 63 percent of white students receive a BA within six years of initial college entry, compared to just 41 percent of black students. The size of this gap, together with its substantial contribution to racial inequality in the United States, makes it a crucial area of concern for researchers and policy makers, alike.

Much of what is known about the black-white BA gap focuses on institutional policies, like affirmative action, that are designed to offset the legacy of discrimination in the United States. While this knowledge is important, it doesn’t shed much light on the sources of the BA gap at the population level, or among all black and white students attending all four-year colleges. This is because institutional policies like affirmative action primarily operate in elite or “highly selective” colleges and universities. Yet highly selective institutions represent less than 20 percent of all four-year college destinations, so focusing on the practices and policies that most apply to selective institutions leaves out much of the story.

In a new study, we take a more expansive approach to understanding the black-white BA gap, evaluating the sources of inequality between black and white students at the population level. We examine four aspects of the college process, including students’ initial decision to enter a four-year college, the matchmaking process between students and colleges, the effects of college quality, and students’ academic performance and social engagement while in college.

Our findings confirm that institutional policies and practices like affirmative action do, in fact, lessen the black-white BA gap. However, the impact of these institutional interventions is only about as large as that of actions that black students take at the individual level, if not smaller. In other words, black students’ individual actions contribute equally, if not more, to reducing the black-white BA gap as institutional policies and practices.

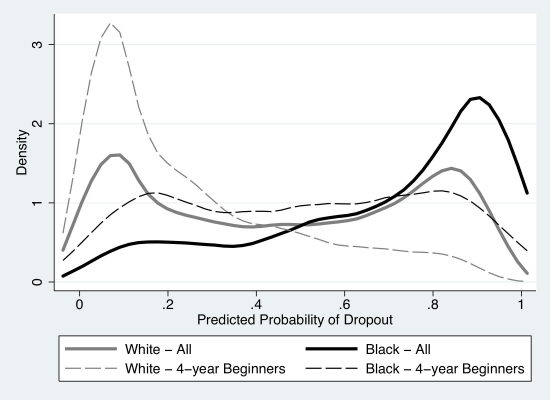

We attribute this finding to a process we call “paradoxical persistence,” which describes black students’ willingness to make choices that align with BA completion despite their lesser store of economic, social, and academic resources as compared with white students. Figure 1 shows the most important example of this process, which centers on the relationship between black students’ likelihood of four-year college dropout versus their likelihood of four-year college entry. As Figure 1, panel A shows, most black high school graduates possess a relatively high probability of four-year college dropout as compared with white high school graduates. This pattern primarily emerges from discrepancies in black and white students’ pre-college academic and economic resources. In fact, black students’ more limited pre-college resources account for about 25 percent of the overall black-white BA gap.

Figure 1 – An Illustration of Paradoxical Persistence

Panel A: The Distribution of Dropout Risk for High School Graduates and College Beginners

Panel B: Entry Probability by Dropout Risk for Black and White High School Graduates

Sources: Education Longitudinal Study 2002, 2004, 2006, 2012, and postsecondary transcript data.

However, as Figure 1, panel B shows, black students also are generally more likely than white students to enroll in four-year colleges, net of their pre-college characteristics. The race gap in the likelihood of enrollment also rises with the level of dropout risk. Consequently, the process of selection into college produces a larger pool of black students at risk of dropout than would be the case if decisions about college entry were similar for both groups of students. It also directly contributes to the high rate of college dropout observed among black students: just 25 percent of black college entrants on average complete a BA, as compared with 50 percent of white college entrants.

Yet black students’ greater willingness to enter a four-year college than similarly situated white students also has an unexpected positive consequence: It decreases the gap in BA attainment between black and white students, or the rate of BA completion among all black and white high school graduates. It does so because a larger absolute number of black high school graduates enter college than would be the case if black and white students made the same college entry decisions, given their pre-college resources. As a result, black high school graduates earn about 9 percent more BA degrees than would be expected if black students entered college at the same rate as similar white students.

Photo by Jonathan Daniels on Unsplash

But what contributes to the BA gap once black and white high school graduates enter college? The primary factor is the difference in academic achievement, measured as college grade point average (GPA), between black and white students, which explains nearly 50 percent of the black-white BA gap. Other important factors include college course taking, college quality (measured based on admissions selectivity), and students’ social engagement in college life.

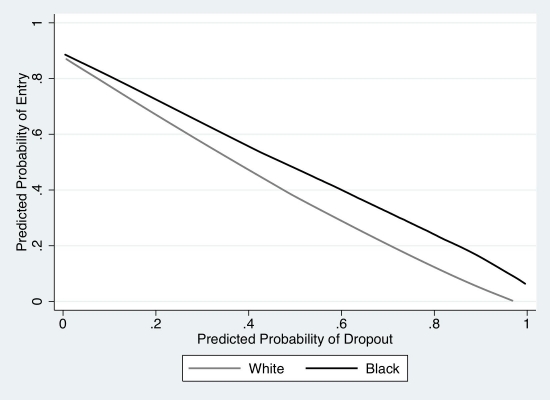

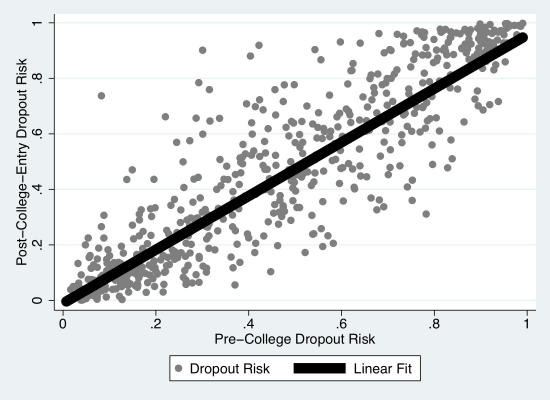

Considering that many of these main explanatory characteristics can be traced to students’ academic performance and economic resources ahead of entry of entering college, it seems possible that pre-college experiences could destine college entrants to certain success or failure. However, as Figure 2 shows, black students’ pre-college experiences in fact are not perfect predictors of their college outcomes. The figure plots black students’ risk of dropout prior to entering college against their risk of dropout after considering two important explanatory factors at the college level, college GPA and college quality.

Figure 2 – Pre-College versus Post-College Dropout Risk Distributions

Sources: Education Longitudinal Study 2002, 2004, 2006, 2012, and postsecondary transcript data; Barron’s Profile of American Colleges 2016; Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System 2004 to 2009.

Although the college-enhanced risk of dropout for most black students remains similar to their pre-college risk, nearly 40 percent of black students modify their risk by 10 percentage points or more. This pattern shows that college experiences meaningfully impact whether or not black students graduate with a BA, regardless of the experiences they have collected before entering college. In this sense, it is beneficial that a higher-than-expected proportion of black students enroll in four-year colleges – even those students with a high risk of dropout – as it is possible these students still might graduate with a BA if adequately supported and directed.

The commitment to higher education that black students demonstrate at the point of college entry and throughout college is a clear resource. But existing institutional policies and practices do not always harness this resource as they could. Given black students’ strong desire to attend college and complete BAs, targeted programs geared toward identifying and addressing these students’ specific academic needs, in particular, may have a substantial, positive effect on the BA completion rate for this large and growing group of college entrants.

- This article is based on the paper ‘The Paradox of Persistence: Explaining the Black-White Gap in Bachelor’s Degree Completion’, in The American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2wclznt

About the authors

Christina Ciocca Eller – Columbia University

Christina Ciocca Eller – Columbia University

Christina Ciocca Eller is a Paul F. Lazarsfeld fellow and doctoral candidate in Sociology at Columbia University. Her research analyzes social and economic inequality by examining how institutional, organizational, and cultural arrangements constrain individual outcomes. She will take up a position as an assistant professor of sociology and social studies at Harvard University in summer 2019.

Thomas A. DiPrete – Columbia University

Thomas A. DiPrete – Columbia University

Thomas A. DiPrete is Giddings Professor of Sociology, co-director of the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy (ISERP), co-director of the Center for the Study of Wealth and Inequality at Columbia University, and a faculty member of the Columbia Population Research Center. DiPrete’s research interests include social stratification, demography, education, economic sociology, and quantitative methodology.