Alleviating climate change by moving to a carbon-neutral economy will not come without cost – those employed in carbon-intensive industries are likely to experience job losses and dislocation, and this can have electoral implications for those that represent them. By studying 2009’s American Clean Energy and Security Act, Daniel Yuichi Kono finds that lawmakers who represented districts with more carbon-intensive workers were less likely to support the bill, but also that this effect was reduced in districts with more generous employment benefits. He argues that these results imply that climate legislation is more likely to succeed when packaged together with policies that help workers, as the Democratic Party has recently proposed in the Green New Deal.

Alleviating climate change by moving to a carbon-neutral economy will not come without cost – those employed in carbon-intensive industries are likely to experience job losses and dislocation, and this can have electoral implications for those that represent them. By studying 2009’s American Clean Energy and Security Act, Daniel Yuichi Kono finds that lawmakers who represented districts with more carbon-intensive workers were less likely to support the bill, but also that this effect was reduced in districts with more generous employment benefits. He argues that these results imply that climate legislation is more likely to succeed when packaged together with policies that help workers, as the Democratic Party has recently proposed in the Green New Deal.

Why have some governments done more than others to combat climate change? The answer is complex and probably involves numerous factors, such as public opinion, media coverage, the influence of fossil fuel industries, and so on. Ultimately, however, the main obstacle to climate action is resistance from those whose livelihoods depend on carbon. Whether they are petroleum workers or coal miners, people who earn a living in carbon-intensive industries are understandably concerned about climate policies that threaten their jobs. This reality requires us to ask what, if anything, can be done to allay their concerns.

One possible solution is to offer compensation to dislocated workers. Such compensation could take many forms: unemployment insurance, retraining and relocation assistance, and even subsidized health care could provide a lifeline for workers who lose their jobs due to environmental regulations. Not only might these programs reduce opposition to carbon restrictions; they might also help “green” politicians maintain the political support of both environmentalists and industrial workers. It is thus important to ask whether welfare spending can facilitate climate action. It is also topical, since the US Democratic Party’s proposed “Green New Deal” incorporates both.

To answer this question, I examine roll-call votes in the US House of Representatives on the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (henceforth the Clean Energy Act). This bill, which remains the US’s sole legislative effort to introduce comprehensive climate legislation, would have established a cap-and-trade system for US carbon emissions. Although supported by most environmental groups, it would have imposed costs on carbon-intensive industries such as coal, steel and cement. I ask, first, whether legislators from carbon-intensive districts were more likely to vote against this bill. I then examine whether generous unemployment insurance made it easier for these legislators to vote in favor.

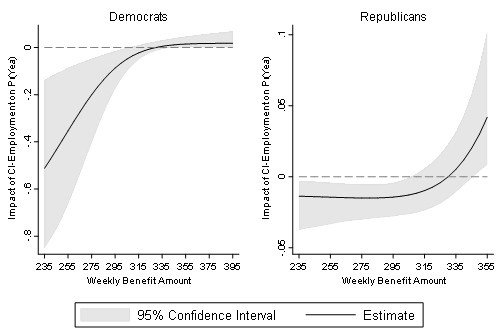

The results are straightforward. First, legislators who represented numerous carbon-intensive workers (measured as a share of district employment) were less likely to vote for the Clean Energy Act. Second, generous unemployment benefits significantly weakened this negative relationship. These results are shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1 – Impact of carbon-intensive employment on Yea votes, conditional on unemployment benefits

In the graphs, the vertical axis shows how a tenth-to-ninetieth-percentile increase in a district’s carbon-intensive employment changed the predicted probability that its legislator supported the Clean Energy Act. The horizontal axis presents values of district unemployment benefits ranging from the tenth to ninetieth percentile. The solid line shows how the effects of carbon-intensive employment changed as unemployment benefits rose. The left-hand and right-hand figures show results for Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

The left-hand figure shows that, where unemployment benefits were low, an increase in carbon-intensive employment reduced the probability that a Democrat voted Yea by 0.51. Concretely, this means reducing Democratic legislators’ likelihood of supporting the bill from a very high 0.95 to a less-than-even 0.44. This effect was smaller, however, where benefits were high, becoming statistically indistinguishable from zero where the weekly benefit amount reached $310 (roughly the sample median). This suggests that Democratic legislators found it easier to vote for the Clean Energy Act—even in the face of high carbon-intensive employment—where workers enjoyed a strong safety net. The right-hand figure tells a similar story for Republicans, but the effects of both carbon-intensive employment and unemployment benefits are very small.

Two points are worth noting. First, the analysis includes numerous controls: legislators’ party affiliations, district economic and demographic characteristics, district partisanship, and so on. This is important, as partisanship alone explains the lion’s share of variation in climate-change votes. The results shown here are net of these other influences. Second, as mentioned above, the main effect of unemployment insurance is to help Democrats vote for the Clean Energy Act. The effects for Republicans are negligible. This is not surprising. Unemployment benefits work because, at the margins, “buying off” carbon-intensive workers helps tip the political scale toward climate action. This can only work, however, where there are pro-climate forces on one side of the scale. Because neither the Republican Party leadership nor strongly Republican districts generate pressures for climate action, Republican legislators have little incentive to vote for climate measures even when social safety nets are in place.

“GreenNewDeal_Presser_020719 (21 of 85)” by Senate Democrats is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Nonetheless, the overall effects of unemployment insurance are large. My results imply that raising all districts’ unemployment benefits from their tenth-percentile value ($235/week) to their ninetieth-percentile value ($360/week) would produce a net gain of 81 votes for the Clean Energy Act. This is much more than the difference between passage and failure: the bill passed by only seven votes and was ultimately not taken up by the Senate. In other words, generous unemployment insurance could permit the passage of climate legislation that would otherwise fail.

These results have clear implications for contemporary political debates. The political left has always struggled to maintain the support of both environmentalists and the working class. If the left appears to prioritize environmental goals above bread-and-butter issues like job security and wages, they risk losing the support of blue-collar workers—as arguably happened in the 2016 US presidential election. One possible solution is to present environmental and labor protection as a package deal that offers something to both constituencies. This may be the idea behind the Democratic Party’s “Green New Deal”, but it is important to note that environment-labor bargains need not take such sweeping form. For example, a carbon tax that used the revenues to assist dislocated workers would be a more market-friendly way of achieving similar goals. In any case, my results suggest that this broad approach could strengthen red-green coalitions that support both labor and environmental protection.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Compensating for the Climate: Unemployment Insurance and Climate Change Votes’ in Political Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2XpEDdT

Daniel Yuichi Kono – University of California, Davis

Daniel Yuichi Kono – University of California, Davis

Daniel Yuichi Kono is a Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Davis. His research focuses on the political economy of international trade, foreign aid, and climate change. His work has appeared in the American Political Science Review, Comparative Political Studies, International Studies Quarterly, the Journal of Politics, and other journals.