A series of studies examines users’ beliefs in social media news stories and suggests practical ways to address the problem, write Alan R. Dennis, Antino Kim, Patricia L. Moravec, and Randall K. Minas.

A series of studies examines users’ beliefs in social media news stories and suggests practical ways to address the problem, write Alan R. Dennis, Antino Kim, Patricia L. Moravec, and Randall K. Minas.

Deception has been a long-running problem on the Internet, and it rose to global attention in 2016 with the Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential election, when “fake news” was deliberately created and spread through social media as part of a disinformation campaign to influence voting. More than 50 per cent of adults get news from social media (primarily Facebook). Most social media users believe that they can detect fake news, but can they really?

Over the past few years, we have conducted a series of studies examining users’ beliefs in social media news stories — both real and fake — and have concluded that we have a major societal problem that will only get worse until we take proactive measures.

Our first study examined whether users could detect fake news stories, whether Facebook’s fake news flag had any effect, and whether users were thinking (measured with electroencephalography (EEG)). We showed users 50 stories (both true and fake) that were circulating in social media at the time and found that 80 per cent of users were no better than chance at detecting fake news; they would have been better off to flip a coin than use their own judgement. Facebook’s fake news flag had no effect on belief in the stories. Telling users what is true and false with a flag simply did not get the user to think more deeply about the article.

Instead, confirmation bias drove beliefs. Participants were more likely to believe and think about headlines that aligned with their political beliefs, and completely ignore stories that clashed with their beliefs. Rather than expend effort to think about the actual truth of a story, participants rejected reality in favour of what they wanted to be true.

So, what can we do about it? One obvious approach is to develop a better fake news flag that can be attached to fake articles. But the fundamental problem with fact-checking every article is that news articles tend to have a short “shelf life.” By the time the results of fact checking are made available, most people have already read the article. The speed with which fake articles travel online outpaces our ability to debunk a given fake news story.

We need a solution that focuses on the source of the story. Unlike article-level fact checking, the source is immediately available for every story that is produced so there is no delay.

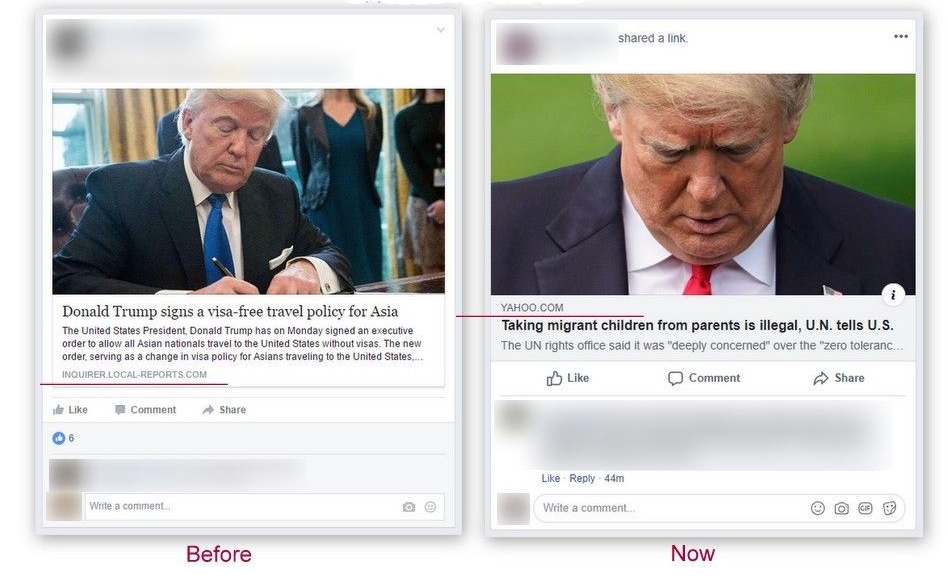

In a second study, we examined whether changing the presentation to highlight the news source would affect beliefs. On Facebook, users do not choose the sources of news articles (stories from many different sources are intermixed) and the source of the story is obscured. At the time of the study, Facebook showed the headline first—along with an eye-catching image—and the source was presented in small print as an afterthought. This design influences users to process the headline without considering the source (e.g., Financial Times or National Enquirer) and makes them more likely to accept the content without the normal consideration of “says who.” Changing the story format to list the source before the headline — an arguably trivial user interface change — made users more sceptical (see the figure below). Despite these promising findings, however, the effects of confirmation bias remained strong — twice as strong as changing the story format.

Figure 1 – Changing story presentation to highlight the news source

Fake news spreads quickly on social media, so we also examined how users’ beliefs affected their actions. We found that belief in the article directly affected whether users would read or share the story, click the like button (which also shares the story), or write a supporting or opposing comment. But confirmation bias had a stronger effect than belief on sharing, liking, and commenting. Users would still like, share, or comment on a story that aligned with their political opinions, even if they doubted its veracity. This is why fake news spreads quickly; users care more about spreading their beliefs than whether the story is true.

The results of the second study were promising, so in a third study we examined the effectiveness of different source rating mechanisms. Source ratings, unlike article ratings, are based on prior articles produced by the source and can be immediately attached to new articles when they are first published; they do not suffer from the time lags of article ratings.

We examined whether users were more strongly influenced by ratings from experts or by ratings from other users. Some pundits have noted that users have become sceptical of experts and have less trust in them than ordinary people. However, ordinary people cannot easily rate the accuracy of news; unlike products, users have no direct experience on which to judge a news story – was Nancy Pelosi really drunk in the video or was it altered? Unless you witnessed the original event, you don’t know.

Our results showed that both expert and user ratings affected beliefs, but that expert ratings were more influential when the rating said the source was fake. When a source was rated as credible, users didn’t care whether the ratings were produced by experts or regular users, and both had small effects. Thus, unlike the flag, attaching the rating created an “interrupt” for confirmation bias that resulted in the user processing the article more critically.

Since our research began in 2016, we have witnessed some positive actions from Facebook and others. Facebook now places the source above the headline and several start-ups produce news source ratings based on evaluations by experts, which are available as a browser plugin. These are steps in the right direction.

Our research shows that social media users are strongly driven by their preexisting beliefs and are easily persuaded to believe fake news that aligns with those beliefs. Users are ill-equipped to defend against fake news, so we need better solutions.

We believe that there is a role for governments in mitigating the fake-news epidemic. The first is through laws regulating false advertising, and libel/slander that protect both individuals and society. Free speech should always remain free, but if money changes hands in the production of fake news, then those responsible should bear the cost.

The second is to realise that fake news is pollution because it pollutes the information environment so that people cannot tell what to believe. Fake news harms democratic societies when consumption and distribution of extreme beliefs divides us. Governments should regulate the information pollution caused by fake news as they regulate other types of pollution, with the producers of fake news paying for the externalities they create.

As social media companies deter the consumption of fake news (through better user interface designs and source ratings) and governments curb the production of it, we may eventually move from a post-truth era back to one in which truth matters. The forces pushing us in the other direction are strong, and it will take a concerted effort for our society to reinvest in this truth.

- This blog post appeared previously at LSE Business Review and is based on the authors’ papers (in the order mentioned in this article):

- P. L. Moravec, R.K. Minas, and A.R. Dennis, “Fake News on Social Media: People Believe What They Want to Believe When It Makes No Sense at All”, MIS Quarterly, in press.

- A. Kim and A.R. Dennis, “Says Who? How News Presentation Format Influences Believability and the Engagement of Social Media Users”, MIS Quarterly, in press.

- A. Kim, P.L. Moravec, and A.R. Dennis, “Combating Fake News on Social Media with Source Ratings: The Effects of User and Expert Reputation Ratings”, Journal of Management Information Systems, in press.

- Featured image by GDJ, under a Pixabay licence

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/31Zy1pi

About the authors

Alan R. Dennis – Indiana University

Alan R. Dennis – Indiana University

Alan R. Dennis is professor of information systems and holds the John T. Chambers Chair of internet systems in the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. He was named a fellow of the Association for Information Systems in 2012. His research focuses on team collaboration, fake news on social media, and information security.

Antino Kim– Indiana University

Antino Kim– Indiana University

Antino Kim is an assistant professor of information systems at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. He received his Ph.D. from the Foster School of Business, University of Washington. His research interests include online piracy and deceptions in social media.

Patricia L. Moravec – University of Texas at Austin

Patricia L. Moravec – University of Texas at Austin

Patricia L. Moravec is an assistant professor of information management at the McCombs School of Business, University of Texas at Austin. She earned her Ph.D. from the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Her research interests include fake news on social media and social media use during disasters.

Randall K. Minas – University of Hawai’i at Manoa

Randall K. Minas – University of Hawai’i at Manoa

Randall K. Minas is an associate professor and holds the Hon Kau and Alice Lee distinguished professorship of information technology management at the Shidler College of Business, University of Hawai’i at Manoa. He received his Ph.D. from the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. His research focuses on information processing biases online in social media, virtual teams, and cybersecurity.