Voters, on the whole, tend to vote on party rather than policy lines, making it less likely that they will select a candidate that actually best represents their views. In new research using 2008 and 2012 election data, Pierce Ekstrom, Brianna Smith, Allison Williams, and Hannah Kim look at whether political disagreement can trigger people to think more about policies than parties. They find that those who are exposed to political disagreement did pay more attention to policy, suggesting that encouraging interactions with those of different minds may be a way of improving people’s democratic decision making.

Voters, on the whole, tend to vote on party rather than policy lines, making it less likely that they will select a candidate that actually best represents their views. In new research using 2008 and 2012 election data, Pierce Ekstrom, Brianna Smith, Allison Williams, and Hannah Kim look at whether political disagreement can trigger people to think more about policies than parties. They find that those who are exposed to political disagreement did pay more attention to policy, suggesting that encouraging interactions with those of different minds may be a way of improving people’s democratic decision making.

There’s a longstanding debate in political science about when (if ever) voters set policy over party. Generally, we hope that a voter chooses candidates not just based on whether they’re Republicans or Democrats but based on whether a given candidate will pursue policies that the voter wants. Not everyone thinks that party-line voting is a bad thing, and the truth is that it’s often good enough to help voters pick candidates who share their policy views. But following the party line can also lead people astray when their preferred party’s candidate does not share their policy views. This is especially likely to happen for those who call themselves Republicans but prefer certain liberal policies, and self-described Democrats who lean more conservative. In 2008, for instance, our data shows that about 27 percent of Republicans were more liberal on key policies than the average independent voter, while about 27 percent of Democrats were more conservative than the average independent. In 2012, we similarly find that 18 percent of Republicans were more liberal than the average independent, while 23 percent of Democrats were more conservative. Data as recent as 2015 indicate that only 60 percent of Democrats are liberal in their policy preferences and only 53 percent of Republicans are conservative.

Given the potential disconnect between party and policy, voters who rely on policy will more likely select the candidate who suits them best. The problem is that policy voting is difficult; it takes time and effort to figure out one’s position on a policy, and even more time and effort to determine which candidate comes closest to sharing that position. So when do voters make that effort? Can we encourage more of them to do so? We thought that political disagreement—tough discussions with close friends and family—could provide the necessary push to get people thinking about politics, and to get them to focus on policy over party.

Why disagreement might be good for voters’ choices

First, disagreement can expose voters to information that they wouldn’t seek out on their own. That information could help them identify the candidate that best represents their policy positions. Second, disagreement with friends and family forces voters to confront the fact that people they care about believe that they are wrong. Faced with that uncomfortable situation, voters may feel pressure to conform to those around them or at least to give some compelling reason that justifies their opinion.

Credit: Chiltepinster [CC BY-SA 3.0]

For example, a Trump-supporting Republican beleaguered by a bunch of Democrat friends may look for ways to defend his preference for Trump. Given that his friends are unlikely to accept “Trump’s the Republican” as a good reason for Trump support, the Republican may look for policy-related considerations that he can use to defend his candidate preference. If the lone Republican is unable to find a better reason to support his preferred candidate, he may begin to change his mind—maybe not by switching sides entirely, but maybe by decreasing his preference for Trump.

To see if disagreement has these healthy effects, we looked at two longitudinal surveys that assessed candidate preferences in the lead-up to the presidential elections in 2008 and 2012. We focused on how respondents’ candidate preferences changed during the last months of each election—specifically, whether they changed to align with respondents’ party identification or their policy preferences. For our 2008 analysis, we used the 2008-2009 panel study from the American National Election Studies (ANES), which recruited a large, representative sample of Americans. For our 2012 analysis, we used the Minnesota Multi-Investigator 2012 Presidential Election Panel Study, which recruited participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. This allows us to replicate our results across two elections.

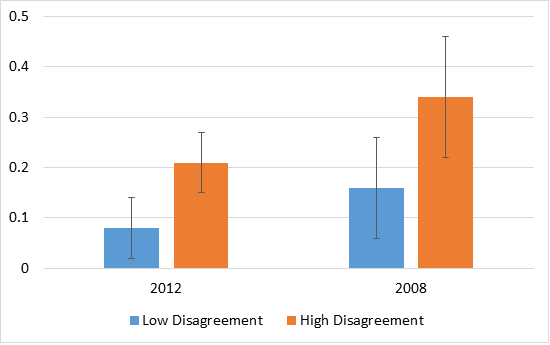

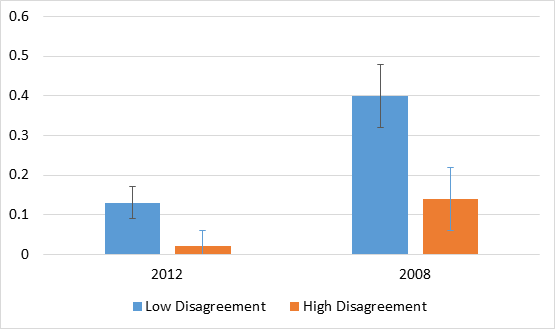

In both samples, those respondents who said that they were surrounded by like-minded others tended to follow the party line. Partisanship strongly predicted how their candidate preferences shifted as the election wore on. Their policy positions had a much weaker effect. Those respondents who said that they experienced frequent or intense disagreement, in contrast, paid more attention to policy. Their positions on key issues in 2008 and 2012 predicted changes in their candidate evaluations. Partisanship had no significant effect among these high-disagreement participants in 2012, and a very weak effect in 2008. We’ve illustrated these results in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 – Percentage Change in Candidate Preference due to Policy

Figure 2 – Percentage Change in Candidate Preference due to Partisanship

In the 2008 ANES data, we also saw a weaker effect of partisanship on vote choice among respondents who experienced a lot of disagreement. Policy had little if any effect on voting, regardless of how much disagreement respondents experienced. We lacked the data to conduct this analysis in the 2012 sample.

Disagreement is linked to policy thinking – but how?

So, people exposed to disagreement seem to approach candidate choice differently—and, we think, more thoughtfully—than those who experience relatively little disagreement. But is it disagreement that caused this difference? It’s possible that a particular type of person experiences more political disagreement, and that this type of person is also more likely to evaluate candidates based on policy.

For example, people who are willing to argue with their friends about politics may also have unusually strong policy preferences. Our data aren’t consistent with that. Disagreement was, if anything, negatively correlated with the extremity of respondents’ policy preferences.

Maybe people who get into political arguments are more politically knowledgeable than people who do not. We did find a positive correlation between disagreement and political knowledge, but it was quite weak in both datasets. Controlling for knowledge did not affect our results.

Finally, maybe people who are willing to maintain relationships with those who disagree with them are less intensely partisan—and thus, less likely to vote the party line. Partisan extremity was negatively correlated with disagreement in our dataset. However, controlling for partisan extremity (and its interaction with disagreement) did not change any of our results. Once again, this potential explanation cannot account for our findings.

Of course, there could always be another factor we didn’t take into account. We can’t be sure that injections of disagreement into the average voter’s life will make them a better citizen. But our evidence is consistent with the idea that disagreement can push people away from party-line voting and—to some extent—closer to policy-based candidate evaluation. In two elections, political disagreement was a common activity among those voters who were most engaged in the hard work of democratic decision-making. Perhaps disagreement can improve the quality of voters’ political participation in future elections as well.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Social Network Disagreement and Reasoned Candidate Preferences’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2yaZM0C

About the authors

Pierce Ekstrom – Washington University in St. Louis

Pierce Ekstrom – Washington University in St. Louis

Pierce D. Ekstrom is a postdoctoral research associate in the Psychology Department at Washington University in St. Louis. He earned his PhD in Social Psychology at the University of Minnesota. He studies the psychology of political conflict.

Brianna Smith – US Naval Academy

Brianna Smith – US Naval Academy

Brianna A. Smith is an assistant professor of Political Science at the US Naval Academy. They earned their PhD in Political Science at the University of Minnesota. Their research focuses on political threat, decision making, and survey methodology.

Allison Williams – University of Minnesota

Allison Williams – University of Minnesota

Allison L. Williams is currently a research associate at Happify. She earned her PhD in Psychology at the University of Minnesota.

Hannah Kim – University of Minnesota

Hannah Kim – University of Minnesota

Hannah Kim is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Minnesota.

Her research interests include voting behavior, attitude change, public opinion on the policy-making process, and the effects of political engagement on polarization.