In both California and Washington State, state candidates for election all participate in one primary, regardless of their party. In new research, Steven Sparks finds that far from eliminating choice from the ballot, the top-two primary system actually encourages candidates to reach out for support beyond their own partisan base by adopting more moderate positions.

In both California and Washington State, state candidates for election all participate in one primary, regardless of their party. In new research, Steven Sparks finds that far from eliminating choice from the ballot, the top-two primary system actually encourages candidates to reach out for support beyond their own partisan base by adopting more moderate positions.

In the last 15 years Washington and California have implemented an electoral system called the top-two primary, which reformed the structure of primary and general elections in their states. Under this system, all candidates running for a given seat (aside from the presidency) run in the same primary election, regardless of their party. The first and second-place finishers proceed to a runoff in the general election, which means that the general election could be between two candidates from the same party. Since enacted, about 17 percent of California’s congressional and legislative contests have resulted in one-party runoff elections, most of which occur in districts that provide a strong electoral advantage to one party.

Editorial pages, think tanks, and party leaders alike have bemoaned that single-party runoffs eliminate choice from the ballot, thus rendering voters from the other party irrelevant. My research finds that the opposite is true.

I studied the rhetoric used on state legislative candidates’ campaign websites to understand how running against an opponent from the same party changes candidates’ campaign strategies. Candidates in one-party contests are actually more likely to talk about partisanship and policy in ways that seek support from voters outside of their own party base.

A long-held conventional wisdom in American politics dictates that Democratic and Republican candidates should adopt extreme positions during a primary election, but then run to the ideological center in the general election. The idea is that whichever candidate adopts views that best represent the “median voter” should earn the most votes, and thus, win the election.

Studies of state legislative and US House elections find that candidates don’t actually follow this axiom. Today, most candidates keep their polarized positions through the general election. A likely reason is that most legislative and congressional contests are increasingly uncompetitive, in large part due to the way in which their geographic boundaries provide an electoral advantage to one party. Out of 7,383 state legislative seats nationwide, just 15 percent are decided by a margin of 10 percentage points or fewer. Five percent of the US population lives in a state legislative district where the winner was decided by a margin smaller than 5 percentage points.

Ultimately, a lack of electoral competition means that elected officials lack incentive to appeal to any voters who are not their own party loyalists. A district that is, say 65 percent Republican is exceedingly unlikely to elect a Democrat —barring extraordinary circumstances, of course (just ask Roy Moore). Consequently, most state legislative elections across the US already face the very problems that critics attribute to the top-two primary. Most elections are a foregone conclusion, so voters lack meaningful choice and those in the minority party are irrelevant.

Featured image credit: Jay Phagan (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

The top-two primary was adopted to address these very issues. Proponents of the reform believed that the traditional primary system favored extreme politicians, contributing to gridlock and dysfunction during the governing process. Reformers hoped that the new rules would invoke moderation in two ways. First, they expected that it would make it easier for moderate candidates to win. Given the choice between two candidates of the same party, moderate and opposite-party voters should vote for the more moderate choice. Second, proponents believed that the new rules would encourage candidates to moderate their positions in order to appeal to a wider range of voters.

The first expectation—that voters would invoke moderation—is not borne out by recent research. As it turns out, voters from the party with no candidate on the ballot often skip one-party contests. Among those who do participate, moderate candidates fare no better in one-party contests because voters simply don’t know which candidate is more moderate. Even if they did, it may still not matter. Moderate voters care less about candidate ideology than conservatives and liberals do, and are likely to vote based on other candidate qualities.

My research investigates the second expectation—whether candidates invoke moderation by appealing to a broader range of the electorate in one-party contests. There is reason to expect that they should, as an important feature of one-party contests is uncertainty. In a heavily-Democratic district, a contest between two Democrats is less likely to be a foregone conclusion. Candidates no longer know for whom Democrats and Republicans will vote, so any voter could may be up for grabs. If two Democratic candidates split the Democratic vote, the independents and Republicans could—at least in theory—determine the outcome.

Candidates tend to respond to competition and uncertainty in several key ways. In particular, they tend to “run scared”, campaigning with greater intensity to mobilize voters and adapting their policy positions to be more palatable to a greater share of voters. Thus, in one-party contests, candidates should respond to uncertainty and perceived competition by broadening the range of voters to whom they try to appeal, thereby self-imposing moderation into the process.

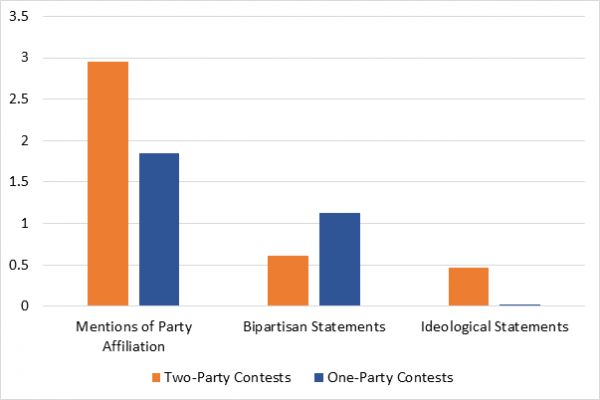

In my analysis of state legislative candidates’ campaign websites, this is precisely how candidates respond. The rhetoric used by candidates in one-party and two-party contests differs in four fundamental ways. First, there are clear differences in the way that candidates talk about partisanship (Figure 1). Candidates in one-party contests make fewer explicit mentions of their own party, make more appeals for bipartisanship, and make fewer statements that reveal a clear ideological leaning.

Figure 1 – Predicted website content, by contest type

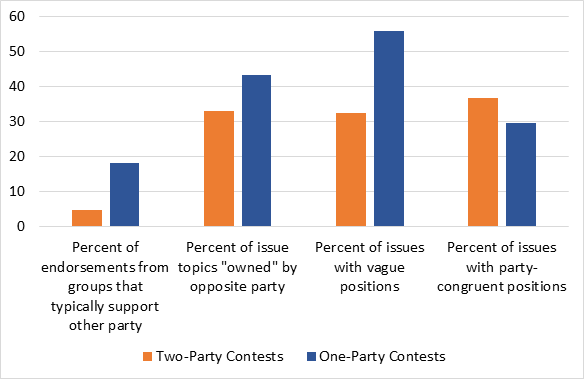

Second, candidates in one-party and two-party contests differ in the endorsements that they list (Figure 2). Endorsements are important because voters use them to make assumptions about candidates’ policy positions. Endorsements from organizations that typically support the opposite party provide information to voters from both parties—for example, a Democrat endorsed by a pro-life organization. In one-party contests, the proportion of candidates’ endorsements that are from groups that typically support the opposite party is four times greater than in two-party contests.

Figure 2- Predicted website content, by contest type

Third, candidates in one-party and two-party contests talk about different types of issues (Figure 2). Aside from the positions that candidates take, voters make assumptions about candidates’ policy positions simply based on the issues that they choose to discuss. For example, voters assume that a Republican is more liberal if they discuss “Democratic” issues like the environment, regardless of the positions they state on that issue. In one-party contests, the proportion of candidates’ issue topics that are “owned” by the opposite party is ten percentage points greater than in two-party contests.

Finally, candidates in one-party contests speak differently about the issues that they choose to discuss (Figure 2). In one-party contests, a smaller proportion of candidates’ stated policy preferences agree with their own party’s platform. Furthermore, the proportion of issues on which candidates state a vague or unclear position is much higher in one-party contests than in two-party contests.

While it is outside the scope of my study to answer how these findings carry over to the policymaking realm, there is strong reason to expect that they do. Past research finds that campaign rhetoric is a strong and reliable predictor of future policymaking efforts, and even vague appeals have predictive power for the way that candidates govern once they are elected.

Ultimately, my findings suggest important consequences for how politicians aim to be responsive to their voters. Although conventional wisdom about candidates fighting for the “median voter” may not hold up in most elections today, findings suggest that the top-two primary imposes a mechanism that encourages candidates to do so. Furthermore, for those who call for term limits as a way to invoke responsiveness (studies show that term limits actually make legislators less responsive), the top-two primary may be a more viable and efficacious pathway to do so.

These findings may also have an effect—although perhaps a subtle one—for incivility among voters. Given evidence that the public mimics the incivility of their political leaders, then efforts by political candidates to broaden their appeal might mean better relationships between supporters of opposing parties.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Polarization and the Top-Two Primary: Moderating Candidate Rhetoric in One-Party Contests‘ in Political Communication.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Zk4qFl

About the author

Steven Sparks – University of Oklahoma

Steven Sparks – University of Oklahoma

Dr. Steven Sparks is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oklahoma. His research focuses on political behavior and state-level politics in the American context.

The USA is a republic — biut not a representative democracy.

The problem is constitutional, and the probability of major democratic reform is tiny.. Most US opinion leaders and manipulations act as if the deeply flawed US cqedstitution came down from the mountain on stone tablets.

The contradictions of the winner take all voting system makes representative democratic legislatures impossible.

The undemocratic dysfunction of the legislatures then culminates in the elected partisan presidency..

Ideally the head of state should be a unifier — but the partisan competition for lthe office, especially in the primaries, pushes in the opposite direction.

Unfortunately the contradictory combination of symbolic and executive functions in the office of president is a model the US has exported to other societies in the name of “dsemocracy.” Shamocracy would be a more accurate appellation.

The USA could be a representative democracy only if the legisslatures were populated by politicians elected by citizens exercising equal effective votes, i.e. proportional representation of citizens, (nearly) all of whom are entitled to representation of their choice.

The presidency would be far more predictably unifying if the president were chosen by a supermajority of a democratically elected Congress. The head of government, drawn from Congress, would require the confidence of a Congressional majority..

In other words, for the sake of the world, the USA needs to find its way to democratic parliasmentasry government.

Unfortunately for the world,, the probability of this happening is aspproximately zero.