Both the Republican and Democratic parties accommodate a multitude of views and approaches to campaigning. Some members want to advance specific policies, while others look to win elections at any cost. In new research, Kimberly H. Conger and coauthors look at how these purists and pragmatists are spread across both parties. They find that while Democratic convention delegates tended to balance both their pragmatic and purist tendencies, Republicans were more polarized with the majority belonging to either the most pragmatic or the most purist group.

Convention delegates – those who represent a state and nominate a party’s presidential candidate every four years – occupy a unique space within the Democratic and Republican Party structures. In many ways, they provide the mechanism for the primary functions of the national political parties. Delegates include those who are more pragmatist and want the party to win elections – even at the expense of advancing specific policies – and others who are more purist and believe that advancing specific policies is the way for the party to win elections. But how are both major US political parties divided into ‘purists’ and ‘pragmatists’? And what does this mean for the direction the parties take?

Instead of an “either-or” approach to explaining party goals, strategies, and behavior, we take a “both-and” perspective and find that while it may be hard to determine whether a party as a whole is policy or office driven, it is somewhat easier to identify activists within the party who value purity over pragmatism and vice-versa. Using results from a new study of the 2012 political party convention delegates – the 2012 Convention Delegate Study – we identify distinct factional groups within each party as determined by their group membership, issue attitudes, and affinity toward key party constituencies, then evaluate their commitments to purity or pragmatism.

Credit: Voice of America [Public domain].

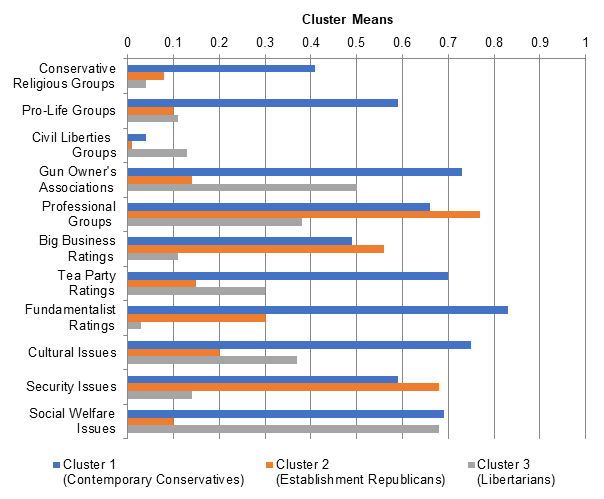

As Figure 1 shows we find three primary factions in the Republican Party; the first, “Contemporary Conservatives,” consists of activists who are likely to be conservative on all three of our policy dimensions: cultural, security, and social welfare issues, to belong to core conservative groups, and to give high ratings to key conservative constituencies. The second faction is “Establishment Republicans,” which pairs a relative lack of ideological zeal with a high likelihood of belonging to professional groups and a strong affinity for big business. Third, are the “Libertarians.” Activists in this cluster are more likely than members of the other two factions to belong to groups emphasizing civil liberties—either civil liberties groups or gun owners’ associations.

Figure 1 – Cluster Analysis of Republican Party Factions

Cluster Means on Indicators of Factional Membership among 2012 Republican National Convention Delegates

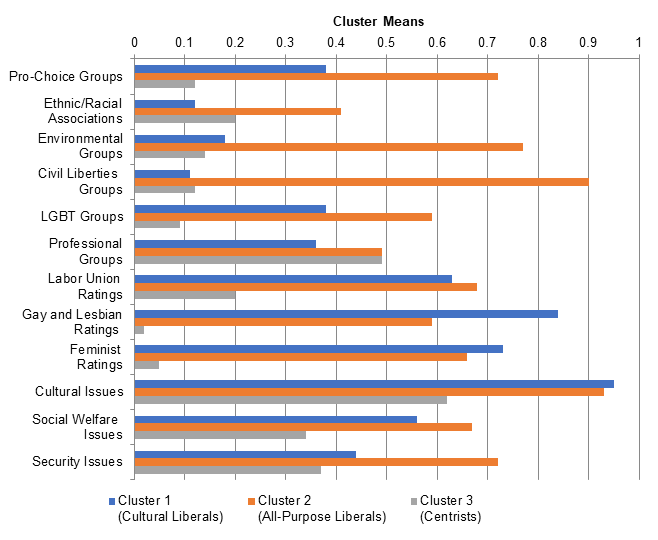

For Democrats (Figure 2), we also find three primary factions. The first are “Cultural Liberals.” This is the Democratic faction most likely to have liberal views on cultural issues and to rate feminists and gays and lesbians warmly. They are, however, moderate in terms of their group membership and their views on social welfare and security issues. The second Democratic cluster are “All-Purpose Liberals.” Members of this faction are the most likely among Democratic delegates to belong to all the core liberal groups and are the most likely to rate labor unions favorably. The final Democratic cluster consists of “Centrists” as its members are relatively low on all the indicators of liberalism. The only indicator on which they score as high as or higher than members of the other two factions is membership in professional groups.

Figure 2 – Cluster Analysis of Democratic Party Factions

Cluster Means on Indicators of Factional Membership among 2012 Democratic National Convention Delegates

The pragmatism/purism divide is just as important as internal factions

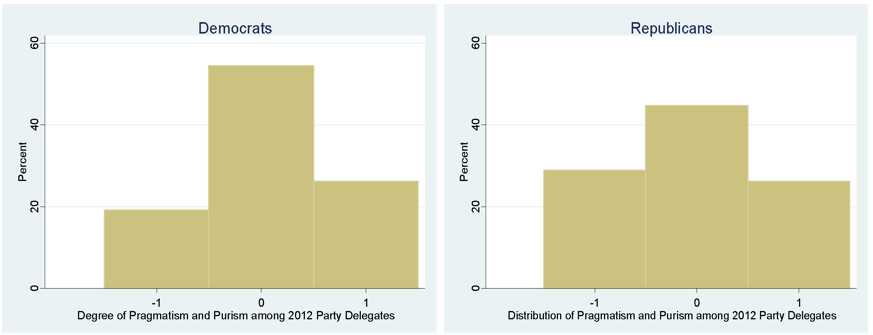

Our final step is to more closely analyze party differences in norms of decision-making. We did this through asking delegates five questions around their support for their own party and their feelings about party vs issue-based activities. At first glance, we can confirm our previous finding from past Convention Delegate Studies; in 2012 party activists – both Democrats and Republicans – wanted to win while pursuing their policy agenda. When we divide the populations based on how they answered our questions, we find that 51 and 49 percent of delegates would be classified as purists and pragmatists, respectively. But, a closer inspection of the data reveals significant cross-party differences in delegates’ attitudes about party pragmatism and purism. Figure 3a reveals that there is not much variation within the 2012 Democratic delegates. Most Democratic delegates, shown in the left-side cluster, internally balance both pragmatic and purist tendencies. Democrats may embrace both pragmatist and purist values because they see little difference between what their respective group wants and what they believe the party wants.

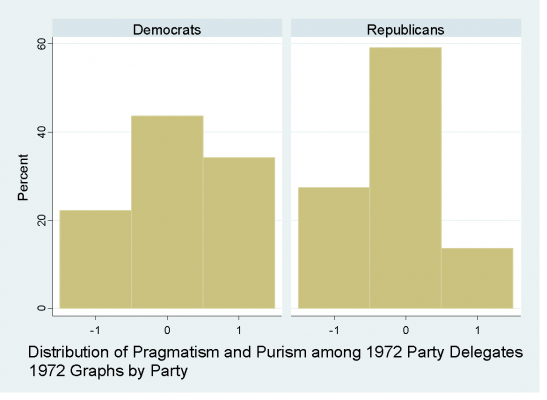

Figure 3 – Distribution of Pragmatism and Purism among Convention Delegates, 1972-2012

A) 2012 Convention Delegate Study

B) 1972 Convention Delegate Study

The right-side cluster of Figure 3a, however, shows more of the Republican Party delegates located at the extreme ends of the spectrum. In other words, about 45 percent of all Republican delegates balance both purist and pragmatic goals while the majority, about 55 percent, is among either the most pragmatic or the most purist. The 2012 Republican delegates mark a significant departure from those in previous years. The Republican Party, dating back to the original 1972 study, has always had most of their delegates internally balance purist and pragmatist norms. Almost 60 percent of the delegates at the 1972 convention re-nominating President Nixon were balanced in this way. But it seems that the 2012 Republican delegates are more internally divided than the (in)famous 1972 McGovern Democrats.

Studying party factionalization is a worthwhile effort at understanding and explaining the contemporary behavior of American political parties. Both Republicans and Democrats are clearly impacted by conflict within their ranks and activists and staff of the parties and their campaign committees spend significant time trying to coordinate among these conflicts and seeking ways to win elections in the midst of the conflict. The Republican Party seems to exhibit more significant factional tension than does the Democratic Party. The Republican delegates to the 2012 party convention by most measures were more likely to espouse purist opinions than their Democratic counterparts. Most important, it seems not have been a single type of purism, but a group of differing purisms advocating for divergent policy stands on a wide variety of issues. While these results are from 2012, they shed important light on internal party processes that shaped the significant conflicts evident in the 2016 presidential primary contests. Looking ahead, it seems very likely that the cycles of wins and losses, as well as the political contexts of each election cycle, will impact both the size and type of faction and its chance of altering the existing status quo.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Group Commitment Among U.S. Party Factions: A Perspective From Democratic and Republican National Convention Delegates’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ngleiz

About the authors

Kimberly H. Conger – University of Cincinnati

Kimberly H. Conger is an assistant professor, Educator of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati. Her research interests include the way religious advocacy makes an impact on American political parties and interest groups, and interest representation in local and state politics.

Rosalyn Cooperman – University of Mary Washington

Rosalyn Cooperman is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of Mary Washington. Her research focuses on the relationship between political parties, PACs, and women candidates, as well as elite attitudes regarding women’s political participation. Cooperman has been a co-principal investigator for the Convention Delegate Studies (CDS) since 2004.

Gregory Shufeldt – Butler University

Gregory Shufeldt is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Butler University. Within American Politics, his research and teaching interests include political parties, state and local politics, and political inequality.

Geoffrey C. Layman – University of Notre

Dame Geoffrey C. Layman is professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and co-editor of the journal Political Behavior. He has published on a wide range of topics, including party politics, religion and politics, public opinion, and electoral behavior.

Kerem Ozan Kalkan – Eastern Kentucky University

Kerem Ozan Kalkan is an associate professor of Political Science at Eastern Kentucky University (EKU). His research interests include intergroup attitudes, public opinion, prejudice toward Muslims, and quantitative methods. He teaches in both political science and master of public administration programs at EKU.

John C. Green – University of Akron

John C. Green is Director of the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics and distinguished professor of Political Science at the University of Akron.

Richard Herrera – Arizona State University

Richard Herrera is associate professor of political science at Arizona State University. His areas of research include political parties and representation.