For many in the US, the ability to file for bankruptcy can act as a form of health insurance, as households who already have little to lose can rely on them. In new research, Youngsoo Jang models different potential healthcare reforms, and finds that those which provide young and low-income households with more access to healthcare services are more likely to reduce the likelihood that they will use the implicit health insurance of bankruptcy.

For many in the US, the ability to file for bankruptcy can act as a form of health insurance, as households who already have little to lose can rely on them. In new research, Youngsoo Jang models different potential healthcare reforms, and finds that those which provide young and low-income households with more access to healthcare services are more likely to reduce the likelihood that they will use the implicit health insurance of bankruptcy.

A growing body of recent studies has examined the interactions between healthcare reforms and household finance. Some have found that healthcare reforms reduce the likelihood of financial harm such as bankruptcy, default, poor credit scores, and unpaid debts. Others show that institutional features of household finance affect households’ health-related decisions. For example, one recent study found that bankruptcy and emergency rooms (ER) can act as implicit health insurance because households with little to lose from bankruptcy rely on them and are less likely to purchase health insurance.

But what is the role of these institutional features in the design of public health insurance policies? Considering the impact of this implicit health insurance, should the US government consider different health insurance policies according to whether bankruptcies and defaults on ER bills are available under some and not others?

One might think that providing health insurance to everyone is always optimal. However, there is a consensus among economists that this is not true: on the one hand, health insurance improves welfare by mitigating health losses by providing more access to healthcare services due to a decrease in out-of-pocket medical expenses. Additionally, health insurance improves welfare because it reduces bankruptcies and defaults on medical bills by insuring financial risks from medical issues. On the other hand, expanding health insurance coverage can hurt overall welfare because more taxes must be levied to pay for the expansion. This increase in taxes increases the distortions of saving and labor supply, reducing average incomes. Therefore, these trade-offs must be quantified to find optimal health insurance policies. My research examines how these institutional features affect the design of optimal health insurance policy in terms of welfare.

Modeling healthcare

To get a better understanding of how health insurance affects bankruptcies, I created a model of how households deal with debts. In my model, households have access to credit and have the option to default on their ER bills and financial debts. When a household defaults, the debt is eliminated, but their credit history is damaged, which in turn hurts their ability to borrow in the future. I also treat people’s health as an investment – by pursuing their own good health, households reduce the likelihood of a severe health-related shock. Health shocks are important – in an overall sense, they can reduce people’s ability to work (their labor productivity), and mean that they are more likely to die earlier.

I also built two models of the US economy: one where people have the option to default and another without that option. Both models perform well in matching life-cycle and cross-sectional moments on income, health insurance, medical expenditures, medical conditions, and emergency room (ER) visits. These models account for important life-cycle and cross-sectional dimensions of health insurance and health inequality. Furthermore, they reproduce the untargeted interrelationships among income, medical conditions, and ER visits.

I pay specially attention to policy aspects currently being discussed in the context of healthcare reform in the US, i.e. an employment-based insurance system with debates between private insurance and Medicaid. I examine the income test for Medicaid, coverage of private health insurance subsidy policies, and a private health insurance reform which stops those who have pre-existing conditions from being charged more. For the rest of the study, I characterize the optimal health insurance as one that maximizes the welfare of a person across their entire life.

“Health Care Costs” by 401(K) 2012 is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0; http://401kcalculator.org

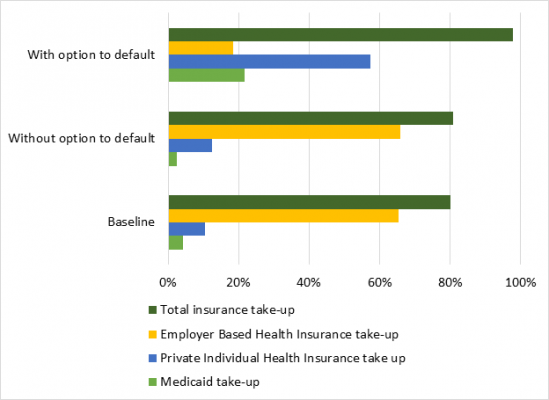

I find that the option to default makes substantial differences in the features of these optimal health insurance policies. Figure 1 shows that in the economy with no option to default, the optimal health insurance policy is close to the health insurance system in the baseline economy. The optimal health insurance policy without the option to default reduces the take up ratio of Medicaid from 4.3 percent to 2.4 percent of working-age households. This policy increases the take-up ratio of private individual health insurance (IHI) by 2.1 percentage points and implements no reform on the private individual health insurance market. In contrast, in the economy with the option to default, the optimal health insurance system is much more redistributive. This optimal health insurance policy provides Medicaid to households whose income is lower than 21.7 percent of working-age households. The optimal health insurance offers a progressive subsidy to all households whose income is above the threshold of income eligibility for Medicaid. The optimal policy reforms the private individual health insurance market by improving coverage rates and preventing price discrimination against pre-existing conditions.

Figure 1 – Health Insurance take-up with and without the Option to Default

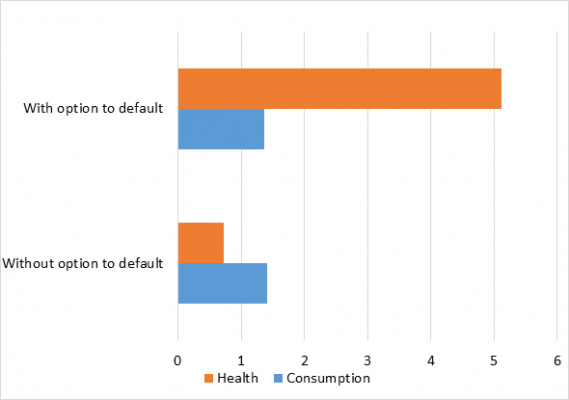

To understand what’s going on here and why, I broke down the changes to household welfare under these models into changes in consumption and changes in health. As Figure 2 shows, in the economy with the option to default, changes in health are the main driving force behind the welfare improvement of the optimal health insurance policy, while these changes are not in the optimal policy without the option to default.

Figure 2 – Percentage in welfare change in health and consumption compared to baseline economy

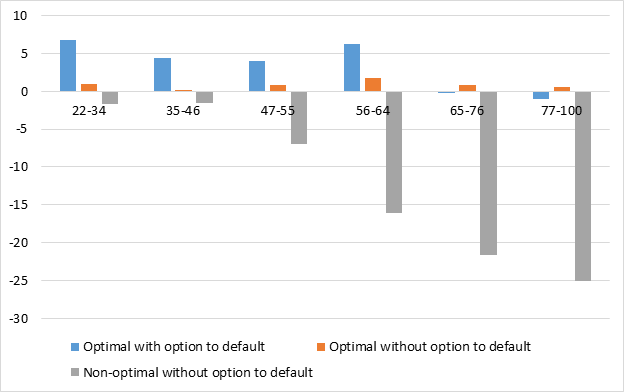

Figure 3 indicates that this gap is driven by different responses of households’ medical spending to each of the optimal health insurance policies. When households have the option to default, the optimal health insurance policy increases young and low-income households’ medical spending, which decreases the overall level and dispersion of health risks and improves health. However, without the option to default, the optimal policy does not bring such large changes in households’ medical spending, which leads to smaller changes in health than the optimal health insurance with the option to default does. This disparity is driven not because the two optimal health insurance policies are different but because households’ medical spending behavior is different. When I implemented the optimal health insurance policy for the economy with the option to default into the economy without the option to default, this policy did not bring the same overall increases in medical spending over people’s lives.

Figure 3 – Changes in the Average Medical Expenditure from Each of the Baseline Economies by reform option

Note: ‘Non-optimal without option to default’ refers to an economy without an option to default, while implementing the optimal health insurance policy for the economy with the option to default.

How health insurance reforms can reduce household’s reliance on ERs and bankruptcies

This different response of households’ medical spending implies that the option to default acts as implicit health insurance. In the economy with no option to default, households are more cautious in managing their health in a more preventative way, because bad health would otherwise come as a huge financial burden. Thus, the optimal health insurance policy does not require a radical increase in the degree of redistributiveness for health insurance policies.

However, with the option to default, young and low-income households can rely on that option to insure against both health and financial risks. Thus, households with the option to default are less eager to manage their health than households without the option. The optimal health insurance policy reduces dependence on this implicit health insurance by providing young and low-income households with more access to healthcare services. This is because the optimal policy decreases the effective prices of health insurance for young and low-income households. This change leads to an increase in overall levels of medical spending for young and low-income households, which acts as a preventative over their lives. This change in spending means young and low-income households see fewer health shocks and greater improvements in health, thereby enhancing their welfare.

My findings imply that in economies where bankruptcies and defaults are easily accessible, more redistributive healthcare reforms can improve welfare by reducing the dependence on this implicit health insurance and changing households’ medical spending behavior to be more preventative. Policymakers need to take implicit health insurance into account in the design of public health insurance policies because it affects households’ medical spending behavior.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Credit, Default, and Optimal Health Insurance’ published in the SSRN.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2C7GR8F

About the author

Youngsoo Jang – Shanghai University of Finance and Economics

Youngsoo Jang – Shanghai University of Finance and Economics

Youngsoo Jang is an Assistant Professor in the Institute for Advanced Research (IAR) at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.