In the last two decades, cities have been affected by two important trends: gentrification, which has led to more demographically integrated neighborhoods, and the rise of school choice, which breaks the link between where kids live and go to school. In new research, Jennifer Candipan looks at how school choice affects who goes to school in different types of neighborhoods. She finds that in neighborhoods experiencing gentrification, there is a growing gap between the proportion of white children in neighborhoods and attending local schools.

In the last two decades, cities have been affected by two important trends: gentrification, which has led to more demographically integrated neighborhoods, and the rise of school choice, which breaks the link between where kids live and go to school. In new research, Jennifer Candipan looks at how school choice affects who goes to school in different types of neighborhoods. She finds that in neighborhoods experiencing gentrification, there is a growing gap between the proportion of white children in neighborhoods and attending local schools.

For decades in the US, which schools kids are assigned to go to has been based on where they live. Because of this tight link between where a child lives and attends school, the most advantaged neighborhoods often had the highest-resourced schools while the least advantaged neighborhoods had lower-resourced schools. This reciprocal relationship meant that segregated neighborhoods were often served by segregated schools. Since the 1990s, however, this close link between neighborhoods and traditional public schools in the US weakened as school choice, which severs the link between residential and schooling decisions, expanded. Charter schools (a kind of public school which is more autonomous from state and local regulations), in particular, during this period expanded substantially in both the number of schools and students they enrolled. In 2016, nearly 3 in 10 students attended a school that was not the assigned neighborhood school, and that proportion was much higher in urban areas.

In recent research, I examined the implications of the growing school choice movement for the composition of neighborhoods and schools, particularly in areas undergoing socioeconomic change. I find that increasing school choice is linked to growing racial and ethnic differences between who lives in neighborhoods and who attends neighborhood schools.

Over the last two decades as school choice has expanded, neighborhoods across the US have also been changing as gentrification (and socioeconomic ascent, more broadly) has brought white and households with higher socioeconomic status into relatively more diverse city centers. These trends intersect in key ways. School choice means that choosing a neighborhood no longer means families are locked in to certain schools, perhaps facilitating moves to more diverse neighborhoods when there are non-local options available. Enrollment of children in more diverse local schools may not follow, however, since past work finds that white families tend to avoid schools with higher nonwhite or lower-income students, sometimes fleeing to magnet, charter, and private schools. Therefore, the in-migration of families into racially and socioeconomically diverse urban neighborhoods may not produce integrated schools if families choose alternatives other than their assigned neighborhood schools.

In my research, I observed how neighborhood and school racial composition tracked over time in areas where school choice was expanding, and whether this varied in neighborhoods experiencing different trajectories of socioeconomic and demographic change, focusing on neighborhoods experiencing socioeconomic ascent. Do key neighborhood institutions, like schools, change alongside neighborhoods when they ascend along socioeconomic lines? In my study, ‘neighborhood ascent’ means the increase in a neighborhood’s housing values and the socioeconomic status of residents, which results in demographic and socioeconomic status change (at least temporarily). Neighborhood ascent thus offers a counternarrative to residential segregation, giving us an opportunity to examine if school sorting narratives remain true as neighborhoods integrate demographically.

To answer these questions, I constructed a unique dataset of the largest, more diverse school districts in the US. I first calculated the difference between the proportion of non-Hispanic white elementary-age students residing in the neighborhood and local school—what I called the “Neighborhood-School Gap” (NS Gap). Positive numbers for this measure (scaled -100 to 100) indicate that there are proportionally more white students living in the neighborhood than attending their neighborhood school. Then, in a series of analyses, I observed whether and where the NS Gap changed from 2000 to 2010, and which factors were associated with those changes.

My models enabled me to observe how change within the same neighborhood, such as the expansion of choice options, was associated with changes in the neighborhood-school gap. My main school predictor measured choice availability, while my main neighborhood predictor captured different neighborhood socioeconomic status trends including increasing and declining status, status stability for those in the upper socioeconomic status levels and status stability for those in the lower to middle levels of socioeconomic status.

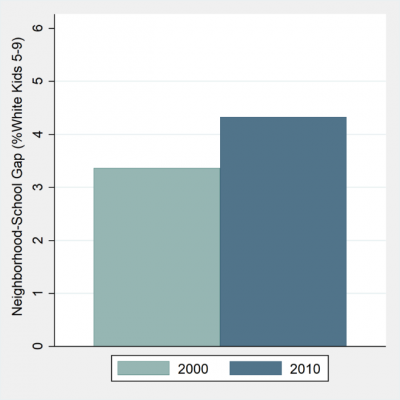

Looking at the data shown in Figure 1, we see that the average neighborhood-school Gap increased from 2000 to 2010, albeit modestly (from about 3.2 to 4.2 percentage points). This overall average, however, masks a great deal of variation between different types of neighborhoods.

Figure 1 – Overall Change in the NS Gap (%White 5-9), 2000-10

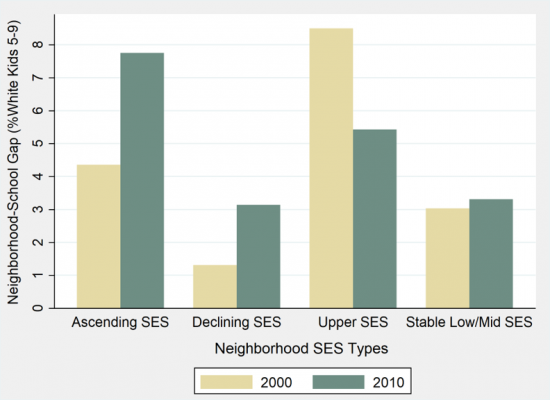

In Figure 2, we see (again looking at unadjusted means) that the growth in the neighborhood-school gap is greatest in socioeconomically ascendant neighborhoods. The link between neighborhood and school composition in socioeconomically stable neighborhoods, on the other hand, does not change much over time.

Figure 2 – Change in the neighborhood-school Gap (%White 5-9) By Neighborhood Type, 2000-10.

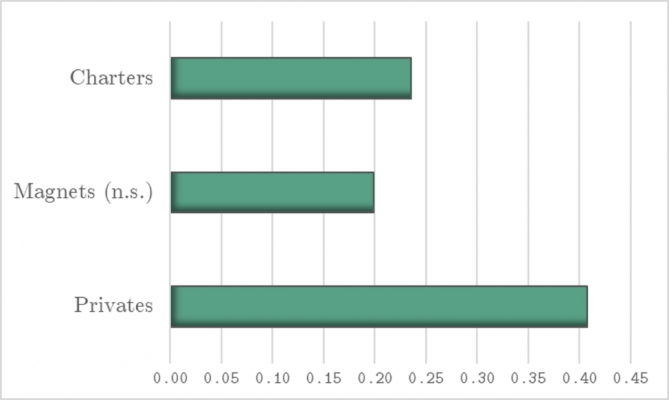

So, does the expansion of charter, magnet and private schools remove the link between neighborhood and school racial composition? Figure 3 presents predicted values for school choice models. An increase in the number of nearby charter and private schools increases the neighborhood-school gap, all factors considered. Each additional nearby charter option increases the neighborhood-school gap by about a quarter of a percent, while each additional private option increases the neighborhood-school gap by over 0.4 percentage points. Note that charter schools expanded more during this period (2000 to 2010), while private school enrollment was relatively stable and even declined in many districts. Nearby magnet schools also increase the neighborhood-school gap, but the coefficient for magnets is non-significant.

Figure 3 – Does School Choice Decouple Neighborhood-School Composition?

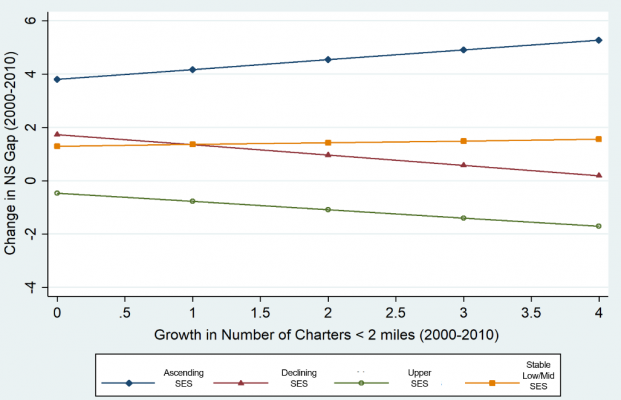

Finally, I looked at whether charter expansion breaks the link between neighborhood-school composition more in socioeconomically ascending neighborhoods. Figure 4 shows results from this model. The blue line represents socioeconomically ascendant neighborhoods. All factors considered, ascendant neighborhoods experienced the greatest growth in the neighborhood-school gap (nearly 4 points), since the line starts out higher. As the number of nearby charter schools in ascendant neighborhoods increased, the neighborhood-school gap grew even more, indicating that a growing charter presence further weakened the neighborhood-school link. On the other hand, charter expansion did little to undermine neighborhood-school composition further in other types of neighborhoods and narrowed the gap in declining and upper-socioeconomic status neighborhoods.

Figure 4 – Charter Growth and Changes in the NS Gap, 2000 to 2010 (by Neighborhood Type)

Integrated Neighborhoods, Segregated Schools?

Overall, I found growing mismatches between neighborhood and school racial/ethnic composition over time— neighborhoods were increasingly composed of more white students than the local school. The compositional mismatch grew the most in neighborhoods experiencing demographic change and socioeconomic ascent, particularly when there were growing nearby alternatives (e.g., charter schools). This suggests that white parents were bypassing the local school while the neighborhood was still changing. The demographic diversity produced via ascent and gentrification at the neighborhood level, therefore, still resulted in stratified educational experiences among kids.

The results of my study have implications for theories of neighborhood and school stratification and raises new questions about how residential and school sorting upholds existing racial hierarchies in a changing educational marketplace and an era of shifting metro migration patterns. These findings also have implications for housing, urban, education, and economic development policies, and add nuance to the idea that school policy is housing policy, and vice versa.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Neighbourhood change and the neighbourhood-school gap’ in Urban Studies.

- Featured image: “2017/365/215 Lockers.” by Ken Bauer is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/35ypHxI

Jennifer Candipan – Harvard University

Jennifer Candipan – Harvard University

Jennifer Candipan is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Sociology at Harvard University and a Postdoctoral Research Affiliate at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Jennifer’s research interests are in stratification, urban sociology, race/ethnicity, and the sociology of education, with specific interests in how social and spatial contexts like neighborhoods and schools produce racial/ethnic and economic inequalities.