Ten years ago today the US Supreme Court decided that corporations were effectively citizens, and able to spend as much as they wanted to on political campaigns independent of candidates. William C.R. Horncastle explains the history of campaign finance which led to the seminal Citizens United ruling in 2010, and how the decision has since led to a massive influx of often anonymous campaign spending by outside groups.

Ten years ago today the US Supreme Court decided that corporations were effectively citizens, and able to spend as much as they wanted to on political campaigns independent of candidates. William C.R. Horncastle explains the history of campaign finance which led to the seminal Citizens United ruling in 2010, and how the decision has since led to a massive influx of often anonymous campaign spending by outside groups.

The 21st January 2020 marks the 10-year anniversary of the seminal Citizens United v. FEC US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) case. Effectively reversing a century’s worth of regulations, while constitutionally protecting the right to unlimited and opaque political spending, Citizens United has resulted in sweeping changes to the financing of political campaigns in the US. While Citizens United is ultimately responsible for the increased role of ‘Super-PACs’ and ‘dark money’ in US elections, the impacts of Citizens United cannot be viewed in isolation. Instead, this case should be seen as the capstone of a string of deregulatory events in political finance. Thus, to understand how SCOTUS came to its decision in Citizens United, we must first understand the history of US Federal political finance.

Early Attempts at Political Finance Reform

As an early adopter of political finance regulations, the US have a long history of regulatory intervention in this area. The first substantive efforts at controlling money in campaigns came in 1907, where the Tillman Act banned corporations from committing direct financial contributions to candidates at the Federal level of government. Disclosure requirements for political donations, as well as contribution limits, were introduced in the years following this, with bans on financial contributions being extended to labour unions through the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. After 1947, political finance remained relatively untouched for almost a quarter of a century.

Watergate and the Issue of Political Finance

While the steady introduction of regulations had produced a system that was relatively strict in theory, the practical application of such rules was of little substance. The resultant framework contained a plethora of loopholes, with the enforcement of regulations also being weak. This changed in the early-1970s, however, where the issue of political finance was thrust into the public eye. In 1972, five men were apprehended after breaking into the Democratic Party headquarters, which they were intending to bug. The event would become the seminal Watergate Scandal, the fallout of which eventually resulted in the near impeachment and resignation of President Nixon. However, as links between this clandestine operation were made to a political fund used by the Committee for the Re-election of the President (CRP) – also known as ‘CREEP’- tasked with winning the 1972 Election of Richard Nixon, the event became a springboard for a flurry of seminal events in the development of political finance regulation.

Post-Watergate Reforms

In 1974, amendments were made to the 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act. Although the 1971 act had extended disclosure requirements for political funds, such as the CRP, the lack of an effective oversight body ensured that the regulations would remain ineffective. The 1974 amendments aimed to rectify this issue, by introducing an independent regulatory agency, the Federal Election Commission (FEC), which would later become one half of the Citizens United v. FEC SCOTUS case. Alongside the production of the FEC, the 1974 amendments introduced spending ceilings on campaigns by candidates, a public funding system for presidential campaigns, and limits on the amounts that citizens could spend to support a candidate, independently of the official campaign.

“Citizens United by Kai” by wiredforlego is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

Money as Speech: Buckley v. Valeo

Although these reforms were considerably more substantive than previous amendments, largely due to the creation of the FEC, they were almost immediately challenged in the SCOTUS, in Buckley v. Valeo. This 1976 case was the first significant step toward a trend of deregulatory judicial intervention, which would shape the direction of future regulations in this area, by questioning the constitutionality of political finance legislation. The central thesis of Buckley was that money, particularly that spent in relation to political campaigns, should be conceptualised as a form of political expression, and not as a financial transaction. Thus, political finance regulations violated the First Amendment of the US Constitution, as such restrictions equated to constraints on political expression. The central message was received by SCOTUS, who deemed that political finance regulations were only constitutional if focussed upon “the prevention of corruption and the appearance of corruption”. Thus, candidate spending ceilings, as well on restrictions on independent political expenditures, were struck down as unconstitutional, with the court determining that such regulations would have little impact on the potential for corruption.

Corporations as People: Citizens United v. FEC

The links between money and speech that had been formalised in Buckley were instrumental in the subsequent Citizens United v. FEC SCOTUS ruling of 2010. In 2002, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act had been passed, which prohibited corporations and labour unions from making ‘electioneering communications’ within a defined period preceding and during an election. In January 2008, non-profit organisation Citizens United attempted to run advertisements for Hillary: The Movie, a scathing documentary about Hillary Clinton, who was running in the forthcoming Democratic primary elections. Such advertisements were deemed to be illegal by the FEC, due to the proximity to the election, who considered them as an attempt to circumvent the electioneering window. Citizens United challenged these claims and the case reached SCOTUS, where the justices built on the foundations of Buckley.

While the case was brought in response to violations of the electioneering window that was introduced in 2002, the implications of Citizens United were much larger, with the court arriving at the conclusion that, as US corporations are produced as associations of people, the corporations themselves should be treated as US citizens. Thus, the combination of Buckley, where money was equated to political speech, and Citizens United, where corporations were deemed to be legal citizens of the US, ensured that corporations would subsequently be afforded the right to coordinate limitless political campaigns, providing that such expenditures were made independently of the candidate’s campaigns.

The Rise of the ‘Super-PAC’

The implications of Citizens United have become wide reaching and significant, chiefly due to the invention and subsequent rise of ‘Super-PACs’. These organisations have been produced as an offshoot of traditional Political Action Committees (PACs). While traditional PACs raise funds to donate to candidate campaigns, therefore being subject to statutory limits on contributions and disclosure requirements, Super-PACs do not donate their funds directly to the candidate. As they commit their funds to independent campaigning, Super-PACs are exempt from the restrictions on direct donations. As a result, the implications of Citizens United have resulted in a circumvention of over a decade’s worth of legislation designed to regulate monetary flows in politics.

While Super-PACs are legally required to disclose their donors, schemes have been developed to subvert these regulations. Exploiting the US tax code, some ‘dark money’ groups utilise the donor anonymity attributed to non-profit 501(c) groups, utilising such associations as shell organisations to funnel large donations into Super-PACs. When disclosing such transactions, the Super-PAC is only required to reveal the name of the 501(c) and not the original source of the funds. While such groups may be considered as independent of each other, investigations reveal that Super-PACs and their donor 501(c) groups often share the same address. One prominent dark money group is the NRA Institute for Legislative Action, who are linked to the National Rifle Association. In the 2016 election cycle alone, this organisation spent over $35m on political campaigning, with no legal requirement to disclose the original sources of their funds.

Political Expenditures since 2010

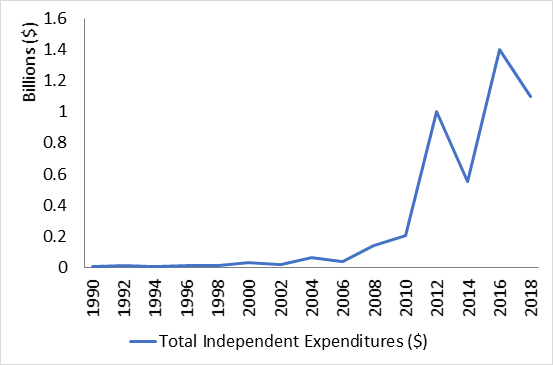

As Figure 1 shows, the anonymity and lack of restrictions on Super-PACs has led to a significant rise in external political spending since 2010. In the 2008 presidential election cycle, for example, independent expenditures totalled $143.7m. By contrast, independent expenditures in the 2012 presidential election totalled $1bn. The increasing trend of independent expenditures continued through the 2016 presidential elections, where $1.4bn was spent in this way, with the 2018 mid-term elections breaking records as the most expensive mid-term election in history. Indeed, current projections suggest that the 2020 elections will eclipse all former spending records. The power of spending by outside groups can be highlighted further when analysing spending patterns in the 2016 presidential election, where spending by outside groups, such as Super-PACs and 501(c) organisations, exceeded candidate spending in 26 races.

Figure 1 – Total Independent Expenditures ($)

Source: OpenSecrets

A Lack of Independence in ‘Independent’ Spending

One of the central principles of Super-PACs concerns the independent nature of their fundraising and expenditure. This independence means that, legally, Super-PACs are not permitted to coordinate their campaigns with the candidate or party that they support. However, this is not the case, with several loopholes being exploited to ensure that information is able to pass between Super-PACs and candidates. For example, in December 2014, Jeb Bush announced that he was “actively exploring the possibility” of running for the presidency. While this statement suggested a confirmation of Bush’s intention to run as a presidential candidate, the choice of words fell short of a confirmation, allowing a temporary coordination with Super-PACs, raising almost $100m prior to his official confirmation in June 2015.

Money and Free Speech: The Future of Campaign Finance in the US

The sustained increase in political spending shows no sign of slowing in the US, with the possibility of an imminent reversal of Citizens United or Buckley seemingly unlikely. SCOTUS has continued to implement the philosophy that underpinned both Buckley and Citizens United, that ‘money is speech’. In 2014, for example, SCOTUS ruled in McCutcheon v. FEC that aggregated donation limits inhibit free speech, with several opposing State court rulings also being overturned by SCOTUS since 2010. The impact of Citizens United has had a significant impact on democracy, eroding the foundations of the political finance and disclosure system in US politics. While the future is unknown, it is likely to involve increased spending, reduced transparency, and increased cleavages of political power.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2RdxcG7

About the author

William Horncastle – University of Birmingham

William Horncastle – University of Birmingham

William Horncastle is a third-year PhD candidate at the University of Birmingham’s Department of Political Science and International Studies. His current research focusses on analysing the development of political finance regulations in advanced liberal democracies. Previously, he has undertaken research into the causes of, and regulatory responses to, the Financial Crisis of 2008. He tweets @willhorncastle.