In Futureproof: Security Aesthetics and the Management of Life, editors D. Asher Ghertner, Hudson McFann and Daniel M. Goldstein bring together contributors to explore how security is perceived and practised through a diverse range of examples of security aesthetics. The development of the concept of security as an aesthetic and sensory experience is an interesting contribution that will prove educational to anyone studying the staging and portrayal of security, writes Courteney J. O’Connor.

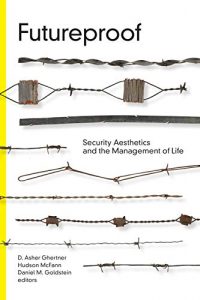

Futureproof: Security Aesthetics and the Management of Life. D. Asher Ghertner, Hudson McFann and Daniel M. Goldstein (eds.). Duke University Press. 2020.

One of the guiding perspectives of the essays collected in Futureproof is that one way or another, security is the guiding mechanism for most, if not all, forms of life. To succeed, security is a necessity. What the volume explores are some of the many ways in which security is perceived and practised and can be seen as such. The construction of security aesthetics in each of the cases examined in this volume is as a response to a threat, either specific or inchoate. By closely examining a wide variety of cases to see how each threat mitigation technique is based in a fear response, the authors show how the aesthetics of security develop over time, according to different contexts, in different places. It is also worth noting that the contributing authors take a very wide perspective on what specifically can represent a threat: far from isolating the interpretation of security to a military (or at least armed) threat, cases considered include such perceived dangers as disease, ‘stranger danger’, house invasion and falling house prices. While an expansive definition, the broadness of the conceptualisation allows for an interesting collection of articles.

One of the guiding perspectives of the essays collected in Futureproof is that one way or another, security is the guiding mechanism for most, if not all, forms of life. To succeed, security is a necessity. What the volume explores are some of the many ways in which security is perceived and practised and can be seen as such. The construction of security aesthetics in each of the cases examined in this volume is as a response to a threat, either specific or inchoate. By closely examining a wide variety of cases to see how each threat mitigation technique is based in a fear response, the authors show how the aesthetics of security develop over time, according to different contexts, in different places. It is also worth noting that the contributing authors take a very wide perspective on what specifically can represent a threat: far from isolating the interpretation of security to a military (or at least armed) threat, cases considered include such perceived dangers as disease, ‘stranger danger’, house invasion and falling house prices. While an expansive definition, the broadness of the conceptualisation allows for an interesting collection of articles.

In the introduction, the editors D. Asher Ghertner, Hudson McFann and Daniel M. Goldstein discuss the ideas of security and security aesthetics. For them, security is provided, and framed, through negation:

security is achieved when threats do not materialize and risks are obviated. Thus, doing security requires the constant staging of an absence… (2).

This is often done through the use of props such as technology or walls. And so, the aesthetics of security come into play: what security looks like depends on the staging of absence, on the method of threat negation. By designing fortresses, screening threats and calibrating vulnerabilities, we as people (and as agents of the state, presumably) are able to satisfy the sensory demands of security (5).

This flows neatly into the initial chapter by Victoria Bernal on the security (or insecurity) aesthetics of cybersecurity through examination of three separate cyberspace and cybersecurity exhibits across three different museums in the United States: The Spy Museum, The San Jose Tech Museum and the San Jose Art Museum. By presenting cyber (in)security according to a particular aesthetic or ‘feel’, each exhibit prompts a different behavioural response in its visitors – fear and resultant state protection; games and mechanical (individually solvable) problems; or dystopia and state overreach (33-62). How an attendee feels about the current state of cyber (in)security depends on the aesthetic, the sensory narrative they experience while learning – so, how a threat is staged matters.

In the second chapter, Austin Zeiderman examines the use of signage throughout Bogotá, Colombia, to demonstrate to the citizenry that they are endangered by any number of threats: household accidents like oil burns or housefires, natural disasters like earthquakes or suspicious figures that could be terrorists (67-69). The primary focus of the chapter, however, is on the high-risk zones of Bogotá that form the city’s outskirts and are zones identified as being highly susceptible to environmental threats such as landslides and floods. Using signage, the city government stages the areas as high risk and a threat to the security of families that choose to (illegally) settle there despite the self-evident risk.

In contrast, the following chapter by Ieva Jusionyte examines the staging of security as violently exclusionary, as state representatives enforce territorial border policies between Arizona, USA, and Sonora, Mexico. Focusing on the aesthetic, sensory and human repercussions of the border wall between the United States and Mexico, this chapter discusses the visual aesthetic of the border itself as threatening, exclusionary: the ‘tactical infrastructure’ used to enforce the border includes ‘fences and gates, roads and bridges, drainage structures and grates, observation zones, boat ramps, lighting and ancillary power systems, as well as remote video surveillance’ (93). Injury and death are not uncommon consequences of the built environment intended to promote the security of those within, endangering the security of those without and in this way performing as a deterrent.

Chapters Four through Six examine, respectively, the aesthetics of security in Honduran neighbourhoods; in Kingston, Jamaica; and in Brooklyn, New York. What security looks like in each of these areas differs widely, but the same thread of the integral nature of how security is staged in each community appears in each study. In Honduras, according to author Jon Horne Carter, the aesthetic of security has changed over time according to which social grouping one belongs. Prior to tougher policies against crime from 2003, facial tattoos identifying gang affiliations provided a certain security – by changing their bodies and appearances in a viscerally identifiable way, the members announced themselves as part of a community at the same time as removing themselves from ‘dehumanizing processes of economic and state violence’ (120). Today, the perceived insecurity of Honduras (including the criminal mafias and organised crime groups) provides the staging for flight from the country.

Rivke Jaffe teaches us that in Kingston, Jamaica, residence in Uptown Kingston has a very different aesthetic of security than does Downtown Kingston, to the extent that the aesthetic of the latter (the sounds, the signage, the manner of speaking) seems threatening to the former, and implicit social rules have developed to prevent too much interaction between the two areas. The gentrification of Brooklyn examined through real estate listings and the framing of content and locale informs Zaire Z. Dinzey Flores and Alexandra Demshock’s analysis of the narrative staging of security in the neighbourhood. In all cases, the way that security is staged by various parties influences the behaviour, either immediate or eventual, of the target (or victim) populations.

Chapters Seven and Eight examine rather different cases of staged security: in the former, Rachel Hall’s analysis focuses on active-shooter drills in US schools. In the latter, Limor Samimian-Darash places the focus on the aesthetics of biosecurity, and the consequences of realising the danger of biosecurity research to the future security of human populations. It is an intriguing idea that the staging or research of threats in order to ensure the future resilience of populations against those threats may in fact introduce new risks to those same populations, and this is a concept I would like to see taken further in future research. By engaging in, and in some cases mandating, active-shooter drills in order to prepare school populations for what they should do in case of a real event, schools themselves become both a stage for trauma and appear as fortresses rather than institutions of learning and safety, especially with the introduction of security equipment and armed guards. In the scientific community, certain lines of research are capable of creating new threats to human health in the course of examination and testing of existing threats. Samimian-Darash discusses the successful aerosolisation of the H5N1 avian influenza in the course of research on the original virus: biosecurity and research laboratories, originally locales of knowledge intended to positively contribute to security, become themselves a risk and undergo an aesthetic transformation as personnel safety protocols become threat-screening and mitigation activities.

The final two chapters, by AbdouMaliq Simone and Alejandra Leal Martínez respectively, examine security aesthetics in urban settings, discussing the nature and form of ‘standby’ in Jakarta, Indonesia (the process and aesthetic of nothing being permanent, even ownership of land or residence as everything exists in a perpetual state of searching for the next best deal) and the urban renewal project in Mexico City, Mexico, pushing back against perceived informality in an attempt to increase the perceived security of specific urban areas. In urban areas, everything from the architecture to the street layouts to surveillance technologies and social groups create a certain aesthetic than lends itself to feelings of either security or insecurity; changing one or more of these elements can transform the perception of security and make people feel safer, even if it does not accomplish this in practice.

The development of the concept of security as an aesthetic and sensory experience is an interesting line of research, and the broad sample of cases evaluated in Futureproof was well chosen. This is a reference text I would recommend for security practitioners as well as advanced students and scholars of security and strategic theories. Far from the typical security text, there are philosophical elements and advanced concepts that lend more to a scholar’s eye, but this text will prove educational for anyone with an interest in the staging and portrayal of security.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Image Credit: Photo by Adam Valstar on Unsplash.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2YJW5wB

About the reviewer

Courteney J. O’Connor – The Australian National University

Courteney J. O’Connor is a PhD candidate with the National Security College of The Australian National University. Her research considers the securitisation of cyberspace and the development of cyber counterintelligence policy and practice.