Fifty years ago the Kerner Commission found that many Blacks felt powerless in the face of unfair racial treatment and categorized twelve areas of grievance that fed into these feelings. In new research, Theodore J. Davis, Jr. finds that Blacks (especially older Blacks) remain more pessimistic than Whites about the state of racial affairs in the US today. He writes that race still matters today, but it matters in ways that are very different from when the Kerner Commission report was released.

Fifty years ago the Kerner Commission found that many Blacks felt powerless in the face of unfair racial treatment and categorized twelve areas of grievance that fed into these feelings. In new research, Theodore J. Davis, Jr. finds that Blacks (especially older Blacks) remain more pessimistic than Whites about the state of racial affairs in the US today. He writes that race still matters today, but it matters in ways that are very different from when the Kerner Commission report was released.

The 1968 Kerner Commission Report

Between 1965 and 1968, race relations in the US were marked by turmoil and civil disturbances across the country. In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders to answer three fundamental questions regarding the civil disturbances: 1) what happened, 2) why did it happen, and 3) what could be done to prevent it from happening again? The Commission later became known as the Kerner Commission after its chair, Judge and former Governor of Illinois, Otto Kerner.

By 1968 the trajectory of race relations and racial disparities with regards to the quality of life and standards of living was such that the Commission wrote: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one White, separate and unequal.”

The Commission’s final report concluded that Blacks’ frustrations and feelings of hopelessness fell into twelve deeply held grievance areas, and it ranked-ordered these grievances based on relative intensity. The first level of complaints involved policing, employment, and housing. The second level involved education, community recreation (i.e., facilities and programs), and the need for a political grievance system that would be effective when it came to addressing Blacks’ concerns. The final level of grievances related to Whites’ attitudes toward Blacks, Blacks’ concerns about governmental programs that were discriminatory, and inadequate programs addressing Blacks’ quality of life.

Racial progress and continued mistreatment 50 years later

Since the start of the twenty-first-century economic recessions, natural disasters, and civil unrest have exposed the continuation of pervasive differences in Blacks and Whites’ perceptions of racial progress about meeting level one and level three grievances.

The level one grievances today are evident in residential segregation, high unemployment, and underemployment among Blacks. Also, several high-profile deaths of Blacks at the hands of White police officers for minor offenses have led to outrage and continued activism.

In August 2014, an 18-year-old Black male in Ferguson, Missouri, Michael Brown, was fatally shot by a White police officer. After a grand jury failed to bring charges against the White officer, several nights of protests and rioting occurred in Ferguson and other cities across the nation.

Eight months later, civil unrest happened again in Baltimore, Maryland, after the death of a 25-year old Black male, Freddie Gray, who sustained life-ending neck and spine injuries while in police custody. That same year, an unarmed Black man was fatally shot in the back by a White police officer who had stopped him for a non-functioning brake light.

In 2019, a Black woman, Atatiana Jefferson, playing video games with her nephew, was shot dead by a police officer through her bedroom window after a welfare check request was made for her. Most recently, in 2020, a Black male, George Floyd, died, from cardiopulmonary arrest, when a White police officer placed his knee on the victim’s neck causing asphyxiation.

These are a few examples of the continuation of level one grievances and perceived failures of the political system to remedy these injustices, which have sparked civil disturbances and protests over the last ten years.

As I’ve mentioned, economic recessions, natural disasters, and civil unrest have exposed that the level three grievances mentioned by the Kerner Commission Report have continued in the form of residential segregation and racial disparities between Blacks’ and Whites’ quality of life and standards of living.

For example, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the US with winds between 100 and 140 miles per hour, becoming one of the costliest and most devastating natural disasters in American history. The storm itself was only half the story. The real story was in the aftermath of this catastrophic disaster when there were levee breaches in New Orleans, causing massive damage.

Tens-of-thousands of New Orleanians gathered in the Superdome – a large downtown sports stadium – to ride out the hurricane. As the high winds of Katrina began to peel back the roof of the Superdome to expose its occupants to the elements, it also revealed one of America’s “elephants in the room.”

Hurricane Katrina revealed racial differences in standards of living and a racial divide in the perceptions concerning racial equality in society. A 2005 Pew study found 71 percent of Blacks felt racial inequality was still a significant problem compared to only 32 percent of Whites.

“DIG14242-072” by LBJ Library is Public Domain.

The aftermath of Katrina also shed light on a racial divide regarding the government’s efforts to address racial disparities in standards of living and quality of life. Many Blacks felt the delayed and inept government responses, at all levels, were as devastating as the hurricane. Blacks’ also expressed concern that the government’s response to the storm was discriminatory.

Pew’s study found that 66 percent of Blacks, compared to only 17 percent of Whites, felt the government’s response to the victims of the levee’s breach would have been faster if the majority of the victims had been White.

The Two-Nations Thesis and the Future

In 1968, The Kerner Commission stated that among the causes of civil unrest for Blacks were frustrations with “unfulfilled expectations” and feelings of “powerlessness.” The outrage and subsequent civil unrest today is still driven by many of the frustrations and feelings of hopelessness among Blacks that the Kerner Commission wrote about.

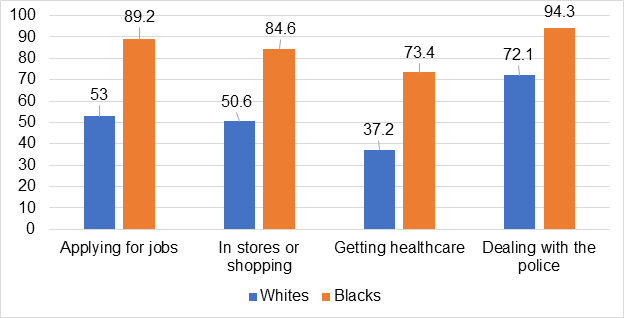

In June 2020, an AP-NORC Center Poll survey asked “would you say Black people are treated more fairly than White people” in applying for jobs, in stores or shopping, getting healthcare, or dealing with the police.

As shown in Figure 1, in the four situations identified, the average gap between Black and White respondents’ perceptions that Whites were treated better was 32.1 percentage points. The average response for Blacks for the four situations was 85.3 percent, compared to 53.2 percent for Whites. The largest gap was regarding applying for jobs, where the difference was 36.2 percent. The smallest response difference between the two groups was 22.2 percent on the question dealing with police mistreatment. The latter indicating that an overwhelming majority of Whites perceive Blacks mistreatment by the police as a problem.

Figure 1 – Perceptions that White people are treated more fairly in…

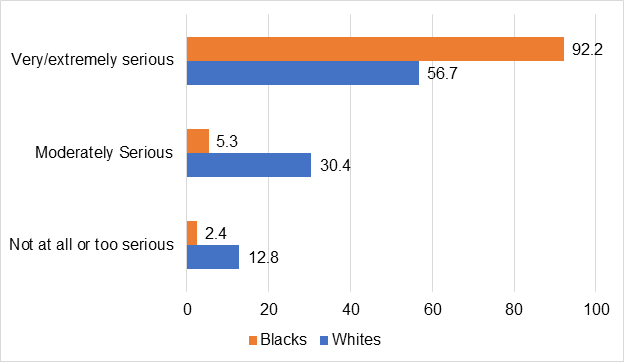

Figure 2 shows a chasm between Blacks and Whites’ perceptions of how serious a problem racism is in the US today. Just over 92 percent of Blacks felt racism was a serious problem compared to under 57 percent of Whites. Only 2.4 percent of Blacks felt racism was not a problem. Thirty percent of Whites felt racism was a moderate problem compared to 5.3 percent of Blacks.

Figure 2 – “How serious a problem do you think racism” is by race?

While differences in perceptions of race relations, racism, and racial progress still differ significantly 50 years after the Kerner Commission’s Report, there may be hope for the future.

One of the core narratives of the Black Lives Matter movement is creating a world that is free of anti-Blackness and racism. Consistent with the findings of my original study, those most pessimistic about racism and the state of race relations today were older Blacks.

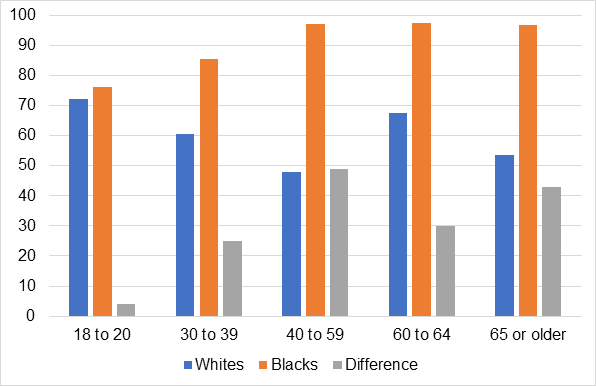

However, the AP-NORC data exposed three patterns with regards to race, age, and perceptions of the seriousness of racism that are worthy of note as shown in Figure 3. First, younger respondents (ages 18-to-29), regardless of their race, saw racism as a serious or very serious problem. Second, the differences in perceptions about the seriousness of racism was only 4 percentage points between Blacks and Whites in the 18-to-29 age group, but averaged around 40 points for the three age groups over 40. Third, perceptions of the “seriousness” of racism decreased as Whites got older but increased among older Blacks.

Figure 3 – Percentage responding racism was a “very” or “extremely” serious problem

The fact that younger Whites saw racism as a “serious” problem sets the table for actually addressing issues surrounding White supremacy, and prejudicial and discriminatory mistreatment of Blacks in the US in the future.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Perceptions of Racial Progress and Mistreatment Today: The Implications for the Kerner Commission’s “Two Nations” Thesis’, in the National Review of Black Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2RMBfbT

About the author

Theodore J. Davis Jr. – University of Delaware

Theodore J. Davis Jr. – University of Delaware

Dr. Theodore J. Davis, Jr. is a Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware. His research and teaching interests include urban politics, politics of inequality and Africana Studies. His current research focus includes urban politics and community development (with a focus on inner city communities); educational achievement gap; the politics of race and socioeconomic inequality; and governance and poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa.