Despite expectations that they would ride Joe Biden’s successful presidential election coattails to an increased majority in the US House of Representatives, the Democrats are likely to find themselves with a reduced majority heading into the 117th Congress. Ryan Williamson and Jamie Carson write that moderates likely lost their seats in this election because they were defending very competitive and often Republican-leaning districts in a nationalized election. With this in mind, they comment that Democrats must now consider how to promote their often diverse messages in ways that satisfies both the progressive and more moderate parts of the party.

Despite expectations that they would ride Joe Biden’s successful presidential election coattails to an increased majority in the US House of Representatives, the Democrats are likely to find themselves with a reduced majority heading into the 117th Congress. Ryan Williamson and Jamie Carson write that moderates likely lost their seats in this election because they were defending very competitive and often Republican-leaning districts in a nationalized election. With this in mind, they comment that Democrats must now consider how to promote their often diverse messages in ways that satisfies both the progressive and more moderate parts of the party.

Despite winning an historic victory over incumbent President Donald Trump in the 2020 elections, the Democratic Party lost seats in the House of Representatives and was unable to gain control of the Senate on November 3rd. The expectation going into Election Day was that Democrats would expand their numbers in both chambers and provide President-Elect Joe Biden with unified control of government.

In the wake of these congressional elections, in-fighting has begun between more moderate members and the more progressive flank of the Democratic Party. Many moderates have blamed progressive messaging as the culprit behind their electoral defeats or narrow victories. House Majority whip Jim Clyburn of South Carolina suggested that calls to “defund the police” hurt Democratic candidates—a sentiment echoed by Virginia Congresswoman Abigail Spanberger, who also urged her colleagues to clarify the message and speak out more strongly against the “socialism” attacks.

However, progressives such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York contend that seats were lost because candidates were instead not progressive enough. Many of the losing Democratic candidates did not support Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, or calls to defund the police. As such, we seek to answer the following question: What role did ideology play in the 2020 House races?

Safer districts mean incumbents can take more liberal positions

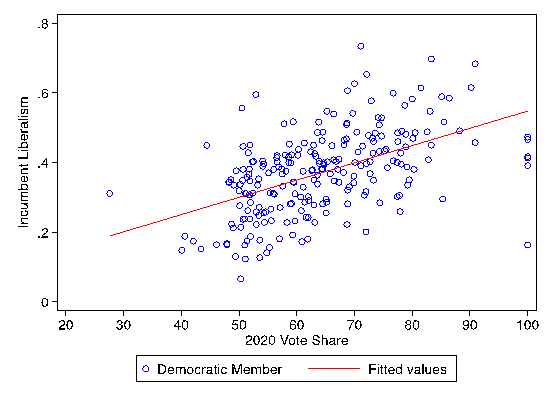

At first blush, there seems to be a positive relationship between ideology and vote share for Democrats in 2020, as shown in Figure 1 below. As incumbent liberalism increases, so does the expected vote share. However, this initial interpretation defies causality. Instead, we should interpret this as follows: as districts become safer for Democratic candidates, those incumbents can adopt more liberal positions. Meanwhile, other incumbents felt they needed to adopt more moderate positions because of the competitiveness of their districts.

Figure 1 – Liberalism of Democratic House incumbents and vote share in 2020 elections

Therefore, we examine the competitiveness of elections in 2018 and 2020. In 2018, there were 194 races where Democrats won 55 percent of more of the vote. That number shrank to 175 in 2020. At the other end of the spectrum, in 2018 there were only 152 elections where Democrats won less than 45 percent of the vote. That number grew to 181 in 2020. For the competitive elections in between this range, Democrats actually fared better in 2020 than in 2018, winning 59.5 percent of close contests compared to only 46.1 percent in 2018. In short, there was a noticeable shift away from the Democratic Party in terms of 2020 vote share. Specifically, the average Democratic vote share in 2018 was 56.1 percent, including uncontested races, but by 2020, that number shrank to 50.6 percent.

It is clear that ideological fit with one’s constituency is still incredibly important in determining election outcomes. This would seem to support the moderates’ argument that the national party brand hurt their chances. However, there are some nuances we would add to that.

“Subway to US Capitol” by Greg Palmer is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The shadow of the 2018 midterms

To a certain extent, it would not have mattered what the national party platform was. Some Democratic candidates’ fates were essentially sealed before the election took place. Many of the Democrat’s gains in 2018 were in extremely competitive or even Republican-leaning districts. For example, one of the Democrats to lose in 2020 was Joe Cunningham of South Carolina, the first Democrat to represent this district in over 30 years. Another loss was Colin Peterson of Minnesota. Though he served 15 terms in Congress, Donald Trump won his district by over 30 points in 2016. Kendra Horn was a surprise victory in deeply red Oklahoma in 2018 and was the only member of the Oklahoma delegation from the Democratic Party. She was also unable to retain her seat.

These three candidates were some of the most conservative Democrats in the 116th Congress, but that moderate ideology is what enabled them to win their more conservative districts in the first place. As such, they were fighting an uphill battle, and it is hard to imagine their elections turning out differently despite taking different positions. That is because US elections have become increasingly nationalized. By that we mean top-down forces exert greater influence on voters’ decisions than state or local considerations. In other words, individual candidate characteristics simply do not matter as much to voters as which party the candidate represents. Voters in these districts especially did not want to support a Democratic candidate.

That is not to say that party is the only thing that matters. In fact, with such a strong party effect, candidates matter more than ever. Individual candidates can indeed potentially sway election outcomes by motivating 4-5 percent of voters to split their ticket, which could be decisive in a competitive election. However, such districts and candidates are in limited supply.

Additionally, it is important to remember that ideology is a complex construct, and voters often do not conceive of issues in the same way as political elites. Indeed, many progressive policy proposals are relatively popular, such as raising the minimum wage, instituting a wealth tax, and certain provisions of the Green New Deal to address the climate crisis. Therefore, Democrats must consider how to message those popular proposals in a way that satisfies both factions of their party.

This is somewhat similar to what Republicans experienced in 2010 with Tea Party candidates. Then, Speaker John Boehner constantly engaged in budget battles that often required Democratic support to pass. This protected the moderate candidates who could present themselves as bipartisan members who work to get things done while simultaneously providing more conservative members with a chance to present themselves as fighting against increased government spending broadly and President Barack Obama specifically. It is a delicate balancing act that will be the key to legislative productivity in the next Congress.

How moderate and progressive Democrats can work together

Furthermore, as the electorate evolves, it will be important for candidates to adapt their positions accordingly. For example, younger voters are more liberal on certain issues and are beginning to turn out in higher numbers. This should allow progressives opportunities to “strike while the iron is hot.” From there, it is up to party leadership to address other, potential bipartisan issues to provide political cover to more moderate members.

Lastly, money is an integral component of a successful campaign. Though early estimates suggest that the 2020 elections cost a record amount, much of the money raised and spent were in a few high-profile races, leaving many other candidates cash-strapped. This may have been a contributing factor to some Democratic defeats, but we will defer to future researchers to make that assessment.

In short, maintaining a majority in the House of Representatives necessarily requires winning competitive districts, which leads to members who adopt more moderate ideological positions. However, moving certain policies in the preferred direction of the more progressive flank of the party is also important to reducing infighting, mobilizing the Democratic base, and addressing the needs of various constituencies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2GUvB5P

About the authors

Ryan Williamson – Auburn University

Ryan Williamson – Auburn University

Ryan Williamson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Auburn University. He received his PhD from the University of Georgia, and previously worked on Capitol Hill as a member of the American Political Science Association’s Congressional Fellowship Program. His interests include Congress and Legislative Procedure, Congressional Elections, Institutional Development, the US Presidency, and Research Design and Methods.

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie L. Carson – University of Georgia

Jamie Carson is the UGA Athletic Association Professor of Public and International Affairs II in the Department of Political Science at The University of Georgia. His primary research interests are in American politics and political institutions, with an emphasis on representation and strategic political behavior. Most of his current research focuses on congressional politics and elections, American political development, and separation of powers.

1 Comments