Even before the COVID-19 pandemic began there had been ongoing debates over whether the US government should forgive some or all of the outstanding student loans it holds. Romesh Vaitilingam details the results of a survey of 42 US expert economists on student debt: the majority agree that paying off all student loans would benefit those on higher incomes more, while more than nine out of ten surveyed agree that debt forgiveness for those on low incomes would be a progressive policy.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic began there had been ongoing debates over whether the US government should forgive some or all of the outstanding student loans it holds. Romesh Vaitilingam details the results of a survey of 42 US expert economists on student debt: the majority agree that paying off all student loans would benefit those on higher incomes more, while more than nine out of ten surveyed agree that debt forgiveness for those on low incomes would be a progressive policy.

The total value of outstanding student loans in the United States currently stands at over $1.6 trillion. During the COVID-19 crisis, federal student loan payments have been suspended to the end of 2020. Following the presidential election, there have been wider discussions of whether the incoming Biden administration may consider some level of forgiveness of the debt.

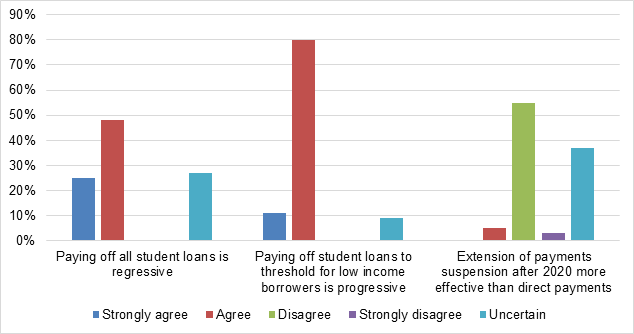

Since 2011, the IGM Forum at the University of Chicago has convened a panel of US experts on economics to survey them every two to three weeks on key issues facing the US and the world. (A European expert panel was added in 2016.) As part of these surveys, we invited our US panel to express their views on student debt forgiveness, and asked them to consider whether policy proposals such as having the government issue additional debt to pay off all current outstanding student loans would be a net regressive or a progressive measure, if payments were up to a threshold for borrowers whose income was below a certain level. We also asked them if they agreed that the extension of the suspension of payments on student loans after the end of the year would support the post-COVID-19 recovery more effectively than using an equivalent amount of money to make direct payments. Of our 43 US experts, 42 participated in the survey. Figure 1 gives an overview of the results.

Figure 1 – US expert economists’ views on student debt proposals

Paying off all student loans

On whether cancelling all student debt would be regressive – that is, benefiting people on higher incomes more than those on lower incomes – nearly three-quarters of the panel agreed, over a quarter were uncertain, and no one disagreed. Weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 25 percent of the panel strongly agreed, 48 percent agreed, and 27 percent were uncertain.

More details on the experts’ views come in the short comments that they are able to include when they participate in the survey. For example, David Autor at MIT, who strongly agrees with the statement, says: ‘Alongside my kids’ student loans, I’d like the government to pay off my mortgage. If the latter idea shocks you, the first one should too.’ Anil Kashyap at Chicago points to a recent Washington Post article by Adam Looney at the University of Utah and Brookings, as well as his earlier piece with Sandy Baum which both make the point that more student debt is held by high-income households compared to those on low incomes.

Other panelists also direct us to background reading. Judith Chevalier at Yale notes: ‘While the Dynarski paper I cite is a few years old, the central finding that many people with substantial earnings have loans remains true’; and James Stock at Harvard links to another Brookings piece by Adam Looney analyzing Senator Elizabeth Warren’s (D-MA) proposal during the Democratic primaries to forgive up to $50,000 of student debt for borrowers with household incomes of less than $250,000.

A number of experts refer to the characteristics of the likely beneficiaries of debt forgiveness. Eric Maskin at Harvard comments: ‘Blanket loan forgiveness would help those who went to college at the expense of those who didn’t’; Joseph Altonji at Yale remarks: ‘College graduates and advanced degree holders have higher earnings along with student loans’; and Aaron Edlin at Berkeley adds: ‘College graduates earn more than non-graduates though presumably those who pay off loans or didn’t borrow and wouldn’t benefit earn even more.’

Austan Goolsbee at Chicago, who says he is uncertain, commented that: ‘The largest dollar amounts of student debt come from professional schools – MD, JD, MBAs. Waiving those is high income oriented.’ Richard Schmalensee at MIT adds: ‘Because of for-profit schools that added little value, one can’t be confident that former students have above-average median wealth.’ But Steven Kaplan at Chicago concludes: ‘Whether regressive or not, it is not a good idea for fairness and efficiency reasons.’

Several of the experts who say they are uncertain do so because it is unclear how paying off all student loans would ultimately be funded. Ray Fair at Yale says: ‘It depends on how the government debt will eventually be paid off.’ And Emmanuel Saez at Berkeley remarks: ‘Depends on how the government debt is going be repaid: progressive versus regressive taxation, or implicit inflation tax’.

Abhijit Banerjee at MIT, who agrees with the statement, nevertheless notes: ‘The answer depends on the financing of the extra government debt. I am assuming that it will be financed like everything else.’ Robert Hall at Stanford is of a similar view: ‘Depends on how the incremental debt is financed, a guessing game. But why would we think of paying off debt of people who are well off?’ And Daron Acemoglu at MIT says: ‘Would depend on how it’s done. Yes lots of student debt among those earning more than 100K a year. So risk of handout to yuppies is there.’

Photo by Mikael Kristenson on Unsplash

Paying off some student loans

On whether forgiving student loans up to a threshold, for borrowers whose income is below a certain level, could be progressive, over 90 percent agreed and again none disagreed. Weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 11 percent of the panel strongly agreed, 80 percent agreed and 9 percent were uncertain.

Of the many who agree, Daron Acemoglu says: ‘Yes this would be much better. Student debt is a problem for low and middle-income households, not those earning more than $100,000 or $150,000.’ Judith Chevalier notes: ‘There is evidence that extant income-driven repayment [IDR] plans are underutilized. Some form of ex post [after the fact] IDR strategy likely sensible.’ Richard Schmalensee comments: ‘Seems more likely than not, if ‘income’ is properly measured.’ And Christopher Udry at Northwestern concludes: ‘The design is not trivial, but it could be done.’

But even among the panelists who agree, there is some caution. David Autor warns: ‘This could create terrible incentives, both for labor supply and (bad) educational investments. Proceed with great caution.’ Robert Shimer at Chicago says: ‘But this may also lead to high implicit marginal tax rates and hence poor incentives.’ And Anil Kashyap notes: ‘Depends on the threshold and the limit, but chosen carefully this could be progressive. There are still major fairness issues with this idea’.

Of the panelists who are uncertain, Jonathan Levin at Stanford says: ‘Perhaps, but seems unlikely if you’re providing funds only to people who have attended college.’ And Caroline Hoxby at Stanford remarks: ‘An empirical, not logical, question. It would depend on the details. Data/analysis would be needed.’

Suspension of payments on student loans

On the potential impact on the recovery of extending the suspension of payments on student loans after the end of this year, a majority disagreed that it would be more effective than devoting the same amount of money to pay people directly, and more than a third were uncertain. Weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 5 percent of the panel agreed, 37 percent were uncertain, 55 percent disagreed, and 3 percent strongly disagreed.

Of the experts who say they are uncertain, Larry Samuelson at Yale says: ‘Both would support recovery, but would be most effective if targeted to those in most need, and it’s not clear which would do this better’; but David Autor points out: ‘General income-based transfer payments could always be used to pay student loans. That’s the beauty of cash over in-kind transfers.’

Others comment on the targeting of the different policies. Among those who say they are uncertain, Caroline Hoxby explains: ‘People with student loans vary from young, living with parents, to older, supporting family on a reduced income. This would poorly targeted relief.’ Of those who disagree with the statement, Steven Kaplan notes: ‘Suspect you could target aid to those more in need than the typical student loan recipient.’

Richard Thaler at Chicago adds: ‘Seems like a weak stimulus. College grads are already saving a lot. It’s the bottom quartile that needs help the most and will spend it.’ And Aaron Edlin comments: Targeting aid to those who need it is most humane. That is probably also the best stimulus. Though stimulus doesn’t stop the pandemic.’

Several panelists reflect on the ease of implementing the two kinds of policy to support the recovery. Emmanuel Saez, who says he is uncertain, notes: ‘Cancelling interest on student debt is easy to implement. Income-based transfers based on current income (not past years’ income) is very hard.’ Austan Goolsbee, who also says he is uncertain, comments: ‘We do know one thing for certain: targeted debt relief is more stimulus than Congress not being able to do anything.’

Jose Scheinkman at Columbia disagrees with the statement but remarks on the potential politics: ‘However it may be easier to suspend student loan payments than to pass income-based transfer payments with a Republican Senate.’

- This blog post is based on the IGM Forum survey, of The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. All comments made by the experts are in the full survey results.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: The post gives the views of its authors, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3qLZvLE

About the author

Romesh Vaitilingam

Romesh Vaitilingam

Romesh Vaitilingam is an economics writer and communications consultant, and the editor of CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and editor-in-chief of the Economics Observatory. He is also a member of the editorial board of VoxEU. Romesh is the author of numerous articles and several successful books, including The Financial Times Guide to Using the Financial Pages (FT-Prentice Hall), now in its sixth edition (2011). As a specialist in translating economic and financial concepts into everyday language, Romesh has advised a number of institutions, including the Royal Economic Society, the European Economic Association, the Centre for Economic Policy Research and the IGM Forum’s Economic Experts Panels based at the University of Chicago. In 2003, he was awarded an MBE for services to economic and social science.He tweets at @econromesh.

This is indeed a very important step from the US government to support the people during this difficult time. I live in another part of the world and, unfortunately, not everything is so rosy with us regarding debt forgiveness …

Why are these economists concerned at all about how federal student loan debt forgiveness is “funded”?!? Being the sole issuer of its own sovereign currency, the federal government is self-funding. This won’t cost taxpayers a dime.