Few areas of social life have attracted as much commentary as the alleged rise of ‘news bubbles’ and their supposed contribution to escalating political polarization in the USA under Trump or in the UK in the alleged ‘Brexitland’ period 2016-20. Yet by examining the relatively small amount of research on what news sources people use – their ‘news diets’ – Ken Newton argues for a much more optimistic view. Most citizens still use different and diverse sources to gain political news.

A wide range of conflicting theories flourish about the power of the media, the influence of fake news, whether people live in echo chambers and opinion bubbles and (if so) to what extent, the influence exerted by social media websites, and the polarising effects of some cable news and papers. Some of this is little more than clickbait designed to feed moral panics. But even serious research can be built around little more than assumptions and speculation.

We need to generate more and better research about what can be called people’s ‘news diets’. In the same way that a balanced diet is a necessity for good health, so a balanced news diet is essential for healthy democratic politics. Democracies should sustain diverse sources of political information and opinion, and, so far as possible, citizens should use them in making their political judgements. Now we know quite a lot about the supply side of news – we know who produces and delivers radio, TV, print media, social media and other web sources. Yet we are still largely ignorant of the no less important demand side, that is the range and content of the news sources that citizens access or are exposed to. The result has been a lop-sided debate that focusses on the supply side but largely overlooks the demand side.

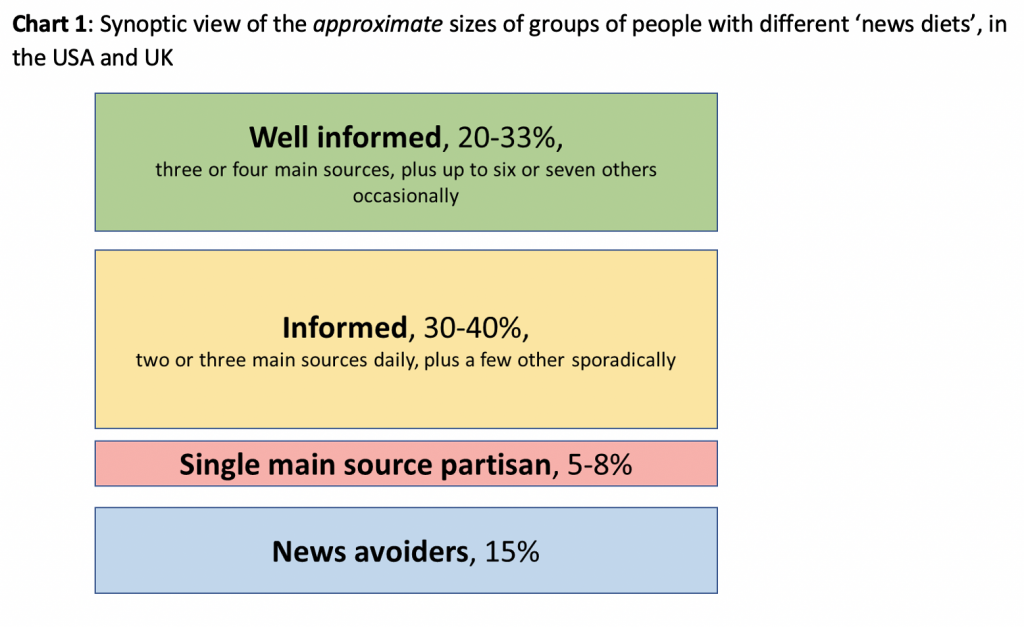

However, there is at least some research on the news diets of citizens. What little there is points to roughly the same broadly pluralist and relatively reassuring conclusions, at least for the UK and the USA. Chart 1 shows how citizens break down across the rough groupings suggested by the available research.

There are four main groups in the population:

- Between a fifth and a third regularly access three to four sources of news (radio, TV, print media, and the web) and a few others occasionally.

- The largest group of around 40 per cent of people keep up with the news, with two to three main sources in a typical day and a few others sporadically.

- The smallest group of 5-8 per cent rely heavily on one source of news, which may be partisan or impartial.

- About 15 per cent of people are news avoiders, though they come across information in other ways.

In all these categories, especially the single-source group, bear in mind the importance of internally pluralist news sources, which has generally been overlooked. In Britain, the BBC is crucial because it is easily the largest single news source and because it is trustworthy and pluralist.

In normal times, people’s patterns of news gathering follow the routines of their daily lives:

- the radio at breakfast and in the car;

- newspaper on public transport or in the lunch break;

- the evening news and late-night comedy on TV;

- grazing news intermittently in free moments on the web.

Interest in the news usually peaks at times of national crisis, such as 9/11 in the USA or the London bombings in 2005, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. At such times, the UK turns to the BBC for trustworthy and up-to-date information. Different mediums are also chosen for the kind of news and opinion they carry:

- newspapers and TV for current news;

- Sunday papers for opinions pieces;

- TV for breaking news and opinion;

- radio while multi-tasking,

- the web for breaking news and following particular items of interest.

- People with an interest in special issues are inclined to scan many sources and use aggregator sites. And

- Digital news is accessed primarily by those who use the computer at work.

Newspapers, TV, and radio remain the most popular sources of political news, though increasing numbers of people are turning to the web. Even so, the most widely used web sites for news in our hyper-pluralist age are those of the heritage media. The New York Times, the Mail Online, Washington Post, Guardian and NBC are market leaders. Few people use the big platform social websites for political news – as against news about friends, celebrities, entertainment, the weather and sport. Those who do get news from Facebook, Twitter, and so on, are primarily the most politically active people who regularly access other news sources as well.

What little evidence there is suggests that few people rely exclusively on any one source of news, whether partisan or internally pluralist. And this applies to the minority who rely heavily on Fox News and on the social media websites. Ofcom Research (Figure 4.59 in their Communications Market Report, 2012) finds surprisingly large numbers accessing both the Guardian and the Telegraph, or the Independent and Telegraph, and even the Sun, BBC, and MailOnline. In the US, visitors to stormfront.org (a site for ‘White nationalists…the new White minority’) were twice as likely to visit nytimes.com as those who called up Yahoo! News.

The main lesson to draw from this limited amount of research is that most people in the UK and USA have a moderately mixed and pluralist news diet. It is true that substantial minorities tend to avoid the news, or concentrate on a single source. But a large minority also regularly access four, five, six or more new sources. More research may yet change the picture above. But if this synoptic view is indeed well-founded then we will have to assess many of the popular myths about media power. We also must re-appraise some of the current accepted wisdom in academic research about the influence of both the heritage and digital media over popular attitudes and behaviour.

- This article first appeared at British Politics and Policy at LSE and gives an updated summary of Chapter 11 of the book, Surprising New – How the Media Affect (And Do Not Affect) Politics.

- Featured image by Good Good Good on Unsplash.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: The post gives the views of its authors, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3t9yylq

About the author

Ken Newton – University of Southampton

Ken Newton is Professor Emeritus in Politics at the University of Southampton. This post gives an updated summary of Ch.11 in his book, Surprising New – How the Media Affect (And Do Not Affect) Politics.