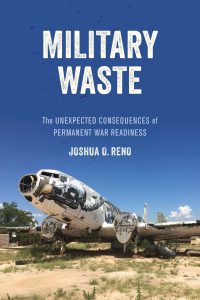

In Military Waste: The Unexpected Consequences of Permanent War Readiness, Joshua O. Reno offers a new ethnographic study of the long retired physical manifestations of the US military-industrial complex in order to unravel the impact of US military waste on the people and communities living outside of formal war zones. This book is an essential contribution to the larger global conversation about the effects of war on the socio-political health of nations and the lasting environmental impact of its psychological residues and material remnants, writes Dr Joanna Rozpedowski.

Military Waste: The Unexpected Consequences of Permanent War Readiness. Joshua O. Reno. University of California Press. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

‘U.S. Military Produces More Greenhouse Gas Emissions Than up to 140 Countries’ reads the headline of one of the popular American weeklies in June 2019. ‘The U.S. military emits more greenhouse gases than Sweden and Denmark,’ recalled another. In an aptly titled journal article, ‘Hidden Carbon Costs of the ‘’Everywhere War’’’, Oliver Belcher et al examined the environmental impact of the world’s third largest military by active personnel (after China and India) and a foremost force in terms of its formidable hardware (3,476 tactical aircraft, 637 unmanned aerial vehicles, 275 surface ships and submarines, 2,831 tanks, 450 ICBM launchers and a total inventory of 5,800 nuclear warheads). Belcher et al reckoned that to accurately account for the US military as a ‘major climate actor’, one must first consider the geopolitical ecology of its global logistical supply chains which enable the acquisition and consumption of hydrocarbon-based fuels. With a 596 billion US dollar annual military spending budget – equivalent to the next seven biggest defence spenders, China, Saudi Arabia, the UK, India, France and Japan, combined – the ecological footprint of the US military is proportionally staggering.

Studies have shown that the U.S. Department of Defense remains the world’s single largest consumer of oil and a leading emitter of greenhouse gases, second only to China. A single mission can consume as much as 1,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases. Scholars have estimated that between 2001 and 2017, the Department of Defense, along with all service branches, emitted as much as 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases, which is a rough equivalent of driving 255 million passenger vehicles over the course of a year.

Scientists and security analysts have warned for more than a decade that global warming is a potential national security concern and a considerable threat magnifier. Some have even projected that the consequences of global warming – rising seas, powerful storms, famine and diminished access to fresh water – will make regions of the world politically unstable, strain social relations, lead to mass migrations and exacerbate existing refugee crises. Many worry that wars and protracted conflicts will inevitably follow.

Yet, with few exceptions, the military’s significant contribution to climate change and environmental pollution has received scarce attention. Joshua O. Reno’s book, Military Waste: The Unexpected Consequences of Permanent War Readiness, promises to remedy this omission. In his ethnographic study of the long retired physical manifestations of the US military-industrial-Congressional complex, Reno attempts to unravel the impact of such waste on the people and communities outside of formal war zones.

In his opening chapter Reno admits to the inherently wasteful nature of America’s permanent war preparedness and its excesses which permeate and interweave the country’s military and civilian worlds. In addition to the war’s obvious afflictions of human loss, injury and trauma, Reno shows that there are the less ostentatious, but no less injurious, toxic contaminations of the earth’s atmosphere and soil on and around sites where obsolete military debris is put to its final rest.

America’s geographically unbounded empire and its attachment to military hardware and dual-use technologies, combined with a penchant for war, have contributed to the technical mastery and militarisation of outer space and resulted in no less consequential orbital overcrowding and space pollution, issuing its own peculiar extraterrestrial ‘tragedy of the commons’. The American network of bases abroad – a critical infrastructure of US imperialism – has also made a pronounced mark on the fauna and flora of overseas island territories. Massive jet fuel spills, radiation leakages from nuclear-powered naval vessels, radioactivity on nuclear testing sites and harm done to plant species and marine life have all laid waste to sites the US military had once occupied. In Reno’s parlance, the US military has become ‘a vector for the spread of toxicity’ (201) at the affected periphery of its empire with a significant probability of blowback to its core.

Reno points out that consequential policy debates and specific budgetary allocations tend to centre on the necessity of investing in particular machinery and cutting-edge technology, instead of debating the efficacy and costs of maintaining the permanent war economy in the first place or inquiring after the ethically questionable practice of ‘private enrichment from public investment’ (33) that stems from the weapons manufacturers’ lucrative government contracts.

The excessive tolerance of government expenditures on the maintenance of unmatched military superiority and the many ‘creative and horrible ways’ of killing, Reno contends, resides in the American public’s anxiety about falling behind its real and imagined enemies, foreign and domestic. While the former yields the spectacular legacy of war profiteering from entangling foreign alliances, the latter contends with a generational inheritance embedded in America’s revolutionary founding. Here, Reno draws on the uniquely American affection for gun ownership to show parallels and paradoxes between the world’s largest and mightiest military and security apparatus and its heavily armed domestic population.

It is at this point that Reno’s book enters into a conversation with its near contemporaries: namely, Chalmers Johnson’s The Sorrows of Empire (2004) and Christopher Coyne and Abigail Hall’s Tyranny Comes Home: The Domestic Fate of U.S. Militarism (2018), which argued that America’s preparation for interventions and war abroad has fundamentally affected domestic institutions, values and liberties at home. An aggressive empire with a militaristic foreign policy runs the risk of fraying the social fabric and changing the character of its citizens. The rise of state surveillance, mass shootings and mass casualties, the militarisation of domestic law enforcement and expanding use of drones are not accidental but inevitable by-products of foreign interventions, which threaten to severely damage, if not destroy, the democratic foundation of the American republic. America’s squandered greatness – a self-inflicted wound permeating its militaristic core – has already rendered its historic providential mission obsolete and will undoubtedly cast the country in the eyes of its peers and competitors into further disrepute as its political and moral values decay at the expense of harnessing its military ethos.

Yet, Reno’s anthropological study is also a commentary on America’s creativity and entrepreneurial spirit. The author draws on the experiences of local conservationists to illustrate how the phenomenon of America’s perpetual war preparation ties with environmental devastation and oddly aids in its restoration. Reno’s book casts light on individuals who have used surplus military warcraft for coral coastline and reef restoration in places like Florida’s Key West. Here, ruin-scapes of dilapidated military apparatus can also become places of ‘imaginative possibility’ (86). America’s sunken military ships are thus impiously ‘memorialized’ (93) as reused and repurposed military waste, raising the possibility that the true worth of America’s impressive warcraft – irrespective of its astonishingly high research and development cost – might thus be found more in its storage, in the scrap yard or submerged and vanquished on the bottom of the ocean rather than in battle.

Joshua Reno’s book is an essential element of a larger global conversation about the effects of war on the socio-political health of nations and the lasting environmental impact of its psychological residues and material remnants. In reading this well-researched, albeit largely academic, study laced with its own specific theoretical context and jargon, one will emerge much better informed about the ways America’s war machines can be demilitarised and repurposed. To render its findings relevant, however, Reno’s study would benefit from a much greater engagement with the policymaking community. As it stands, Military Waste is a diagnostic work of scholarship, which focuses on the multi-pronged effects of the ailment rather than the prophylactic remedies against the pathogens which gives rise to it. Nevertheless, causes cannot be made known without first fully rendering their effects and Reno’s work provides the reader with a wealth of information on this interdisciplinary subject.

- This article originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Image Credit: Old Hercules transport plane, Khe Sanh Combat Base (Ta Con), Vietnam (Paul Mannix CC BY 2.0).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3rPPM6j

About the reviewer

Joanna Rozpedowski

Dr Joanna Rozpedowski is a political scientist and international law scholar based in Washington, DC. She can be found on Twitter @JKROZPEDOWSKI