Elections in between US presidential contests – midterms – often attract lower voter turnout but can have important implications for which party controls Congress. In new research, Till Weber finds that about 10 percent of moderate partisans who had previously voted for the incumbent president’s party are likely to vote for the opposing party at a midterm election. He argues that these voters turn away from the president’s party as a way of reminding the White House that the next presidential election will be won at the center, and that they should pursue more moderate policies.

Elections in between US presidential contests – midterms – often attract lower voter turnout but can have important implications for which party controls Congress. In new research, Till Weber finds that about 10 percent of moderate partisans who had previously voted for the incumbent president’s party are likely to vote for the opposing party at a midterm election. He argues that these voters turn away from the president’s party as a way of reminding the White House that the next presidential election will be won at the center, and that they should pursue more moderate policies.

US midterm elections look odd to the European eye. If their dullness and predictability have a counterpart in the Old World, it would only be in elections to the European Parliament, which occur in a similar environment of low public interest and adverse conditions for the party in control of the national executive. Yet on both sides of the Atlantic, it is precisely this environment that brings to life an ancient creature that persistently refuses to go extinct: the political center. Centrist voters often find their moderate policy views unrepresented during prime-time performances of party polarization. Their big moment comes when elections are repeated off the beaten path.

At midterm – between presidential elections – when most of the nation falls back into apathy or learned patterns, centrists seize the opportunity to voice policy concerns and seek ideological balance. Both these objectives tend to hurt the party of the sitting president. While one may suspect agile independents are at work, survey evidence for all House elections from 1956 through 2018 reveals that pushback rather comes from the president’s own ranks. In an average midterm election, the presidential party sees about 10 percent of its moderate partisan base defect to the opposition.

Moderate partisans (i.e., voters who identify with a particular political party) combine two features that encourage midterm strategizing. Their policy preferences are “sandwiched” between the two major platforms, giving them an incentive to vote against whichever party happened to get the upper hand by snatching the White House two years earlier. At the same time, moderate partisans are still partisans, meaning that they are biased arbiters of political competition. Ideally, they would like to see moderate policy being implemented by an administration of their own stripes. Voting against their allegiance at midterm allows them to remind their party that the next presidential race will be won in the center. The evidence suggests that both these motivations—balancing policy and voicing a warning—need to come together to produce measurable impact.

Featured image credit: Peter Rukavina (Flickr, CC-NC-SA-2.0)

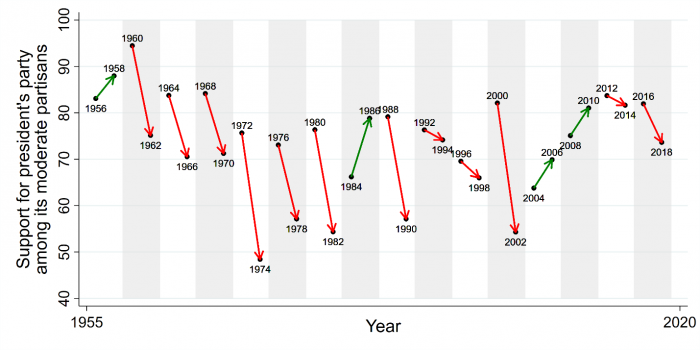

But moderate partisans are too crafty to just vote against the incumbent administration on a routine basis. Consider the variation shown in Figure 1. The arrows indicate how support for the president’s party changed among moderate partisans from a presidential year to the following midterm. While most presidents lost support (red), the arrows vary considerably in length, and even point upward in some cases (green). How does such seemingly erratic behavior reflect reasonable policy concerns?

Figure 1 – Electoral support for the president’s party among its moderate partisans, 1956-2018

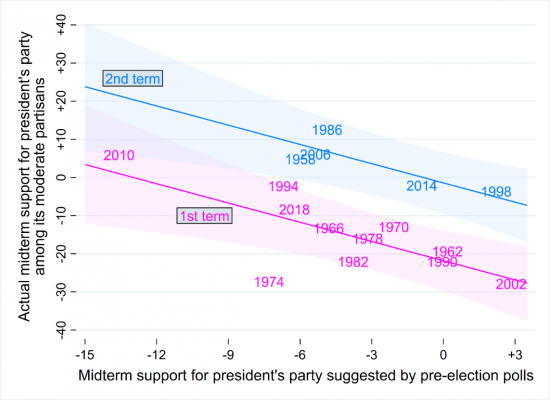

See what happens when we reorganize the data as shown in Figure 2. The length of the arrows from Figure 1 is now plotted on the vertical axis. On the horizontal axis, we see the change of the vote for the presidential party that was predicted by the final Gallup poll before each midterm election, relative to the previous result. Two regression lines are drawn through the data points: one for the president’s first term, and one for the second. As is apparent, the better the president’s party does in the pre-election polls, the larger are its losses among moderate partisans. Moreover, those losses are generally more severe in a president’s first term.

Figure 2 – Midterm support for the president’s party among moderate partisans, predicted by presidential term and pre-election polls

The empirical pattern aptly tells how moderate partisans work the electoral calendar to achieve policy representation. Using the midterm to voice a warning to the next campaign for the White House is most promising when the president faces reelection two years later. In contrast, the blade of the popular verdict has been blunted by the time an administration fights its last Congressional election. This is the force that produces the gap between the two regression lines. Their downward slope reflects the objective of moderate partisans to balance power in Washington more immediately. If the president’s party appears to do well at a midterm election against all odds, clipping its wings will seem more necessary. Vice versa, if a bad defeat is expected, the problem goes away naturally, and moderate partisans will remain on the sidelines, or may even come to the aid of their struggling president. Either way, their choices work against the larger electoral trend—the opposite of what one would expect on the basis of a “mechanical” notion of the center leading the way.

Overall, the behavior of the political center demonstrates more reason than is commonly accorded to the public. As President Biden prepares to defend his agenda in the midterm election of 2022, he does so under the watchful eyes of moderate Democrats, his essential power base.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, European politicians have a superb opportunity to study for their own “midterm” in 2024.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Voice and Balancing in US Congressional Elections’, in Perspectives on Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2T54XNC

About the author

Till Weber – City University of New York

Till Weber – City University of New York

Till Weber is an associate professor of political science at Baruch College & The Graduate Center, City University of New York. His work covers a variety of democratic processes, including voting behavior, party competition, legislative politics, cabinet government, and unicorn migration.