Over the past 70 years, lawyers have argued cases before the US Supreme Court more than 10,000 times, but just under seven percent of these appearances have been by women. In new research, Jonathan S. Hack and Clinton M. Jenkins find that while over time, women have been no less likely to win a Supreme Court case than men, women have had to be, on average, more qualified and experienced compared to their male counterparts in order to be able to appear there in the first place.

Over the past 70 years, lawyers have argued cases before the US Supreme Court more than 10,000 times, but just under seven percent of these appearances have been by women. In new research, Jonathan S. Hack and Clinton M. Jenkins find that while over time, women have been no less likely to win a Supreme Court case than men, women have had to be, on average, more qualified and experienced compared to their male counterparts in order to be able to appear there in the first place.

Arguing a case before the United States Supreme Court is no small feat. It is assumed that law, facts, and compelling legal rationale matter when the justices deliberate, but do the justices – consciously, or not – evaluate the arguments made through a gender (biased) lens?

There are reasons to suspect a gender bias exists among the nation’s highest jurists. Recent work suggests that gender norms factor into how men justices evaluate counsel’s arguments. Others have reported that women attorneys are more likely to be interrupted than men. Even those who argue cases have noted gender discrepancies; in 2011 attorney Lisa Blatt commented, “women have a harder time than men successfully arguing before the Court.”

The possibility that gender might factor into justices’ decision-making has even led some to raise concerns about, “how effective women are at the Supreme Court.” Building upon earlier work, we address this question by asking: Do women advocates disproportionately lose before the Court? If women do lose at overwhelming rates, then parties to a case may shy away from hiring women to represent them. What’s more, if true, this raises serious concerns about the decisions the Supreme Court makes.

To answer our question, we constructed an original data set of all orally argued cases with a signed opinion from 1946 to 2016 and relied upon the Case Access Project at Harvard Law School to extract information about the attorneys arguing before the Court. Of the over 10,000 lawyer–appearances in our dataset, 710 (6.9 percent) are women and 9,514 (93.1 percent) are men.

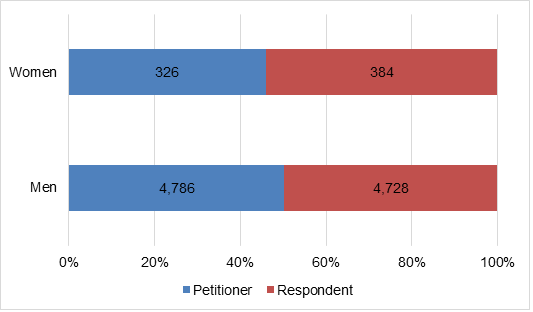

Focusing on how attorney gender is distributed by party to the case, Figure 1 shows that men are relatively evenly divided in terms of representing the petitioner or the respondent. However, of the 710 instances where a woman argued a case, more than half of the time (54.1 percent) it was on behalf of the respondent.

Figure 1 – Supreme Court cases argued by attorney gender

Note: Gender, of course, is a multifaceted concept and treating it as binary excludes those who may not self–identify with these labels. That said, the attorneys in our dataset – to the best of our knowledge – conform to a cisgender binary. For our purposes, a variable coded as either man or woman does not exclude nor force observations into a category that does not fit their gender identity to the best of our knowledge.

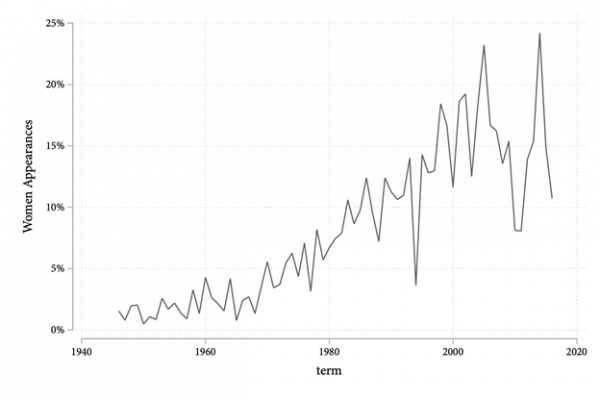

Our analysis revealed two important findings. First, women appear more frequently as time goes on, comprising a larger proportion of the attorneys who litigate before the Court. As Figure 2 shows, starting in the late 1960s through the early–1990s women gradually started solo–arguing more cases before the Court.

Figure 2 – Percentage of Total Women Attorney Solo-Argument Appearances Before the Court

Although 1994 proves to be a bit of an anomaly, the overall upward trend continues into 2016. Importantly, the number of unique appearances for women attorneys – in any given year – never reaches beyond twenty–nine, indicating that the women who argue before the Court are limited to a small cadre of repeat attorneys.

Second, when accounting for other factors influential to the decision–making process, we find no systematic differences in the likelihood of petitioner success when represented by a woman or a man. We reached this finding using logistic regression to model whether the petitioner secures a win before the Supreme Court. Our choice to model whether the petitioner wins is consistent with an extensive literature on the Court’s tendency to overturn lower court decisions.

Photo by Ian Hutchinson on Unsplash

Considering the full results from our model, shown in Figure 3, we find that, over time, women arguing for the petitioner are statistically no more likely to win than are men arguing for the petitioner against another man. Likewise, a man arguing for the petitioner facing a woman is no more likely to win or lose over time than if that man were facing another man. Overall, the gender of the attorneys and the likelihood of winning – relative to that of a man attorney representing the petitioner and facing another man – doesn’t statistically change over time.

Figure 3 – Predictors of success in Supreme Court cases

Ultimately, attorney gender is a poor predictor of success before the Court. It does not appear that women attorneys lose or win cases any more readily than men. Other characteristics such as attorney experience and amici support are more strongly associated with party success. One interpretation may be that women no longer face discrimination in the legal profession or in their appearances before the nation’s highest Court. Such an interpretation might be heralded as some “good news.” For those attorneys who make it before the Court to argue, justice is “gender blind” – a finding that should offer Court observers and citizens alike comfort. However, we caution against this interpretation of our findings.

Instead, we suggest another, more nuanced, interpretation. Although the inability to find evidence of gender bias before the Court is undeniably good, we believe these results also suggest that discrimination against women attorneys continues to be rampant. We demonstrate that once before the Court women fare just as well as men, controlling for other relevant factors.

But here’s the kicker: a brief investigation into the background and experience of the women who argue before the Court finds that, relative to men, more of the women arguing their first case before the Supreme Court did so as government attorneys and/or holding significant prior experience. The men arguing before the Court tend to have far more variation in their backgrounds and prior experience. While men attorneys with varying backgrounds and experience are afforded the opportunity to appear before the Supreme Court, women have had to be, on average, more qualified and experienced to receive the same opportunity.

To the extent gender discrimination occurs in decisions at the Supreme Court it appears to begin well before attorneys make it to oral advocacy.

- This article is based on the paper, “The Attorneys’ Gender: Exploring Counsel Success before the U.S. Supreme Court’, in Political Research Quarterly

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3hHlKjm

About the authors

Jonathan S. Hack – Lehigh University

Jonathan S. Hack – Lehigh University

Jonathan S. Hack is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Political Science at Lehigh University, researching judicial decision-making and institutional design.

Clinton M. Jenkins – Birmingham-Southern College

Clinton M. Jenkins – Birmingham-Southern College

Clinton M. Jenkins is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Birmingham-Southern College. Professor Jenkins’ research focuses on the news media, public opinion, and political socialization in American politics, as well as on survey methodology and political science pedagogy.