In today’s politically polarized environment, late night political comedy is often caustic and personal when aimed at elected officials. But do older and more gentle forms of political comedy still appeal to modern audiences? With this question in mind, Brian Calfano and Lori Han tested a series of political jokes with survey audiences. Those surveyed responded most favorably to Johnny Carson’s style of political humor of the 1970s, compared to modern day ‘Late Night’ humor.

In today’s politically polarized environment, late night political comedy is often caustic and personal when aimed at elected officials. But do older and more gentle forms of political comedy still appeal to modern audiences? With this question in mind, Brian Calfano and Lori Han tested a series of political jokes with survey audiences. Those surveyed responded most favorably to Johnny Carson’s style of political humor of the 1970s, compared to modern day ‘Late Night’ humor.

Television comedy is certainly now more caustic than when Johnny Carson (host of The Tonight Show from 1962-1992) was king of the genre. Certainly, during Trump’s tenure, late night network comedy directed towards the president was often intense and deeply personal. But even if one finds merit in this form of political comedy, do audiences? The answer seems to depend on the audience in question. Partisanship and the difference in left/right political psychologies matter as much in the appraisal of what’s funny as does the proliferation of television offerings. The bottom line today is that an audience exists for just about any form of political comedy or commentary. Well, any form except maybe one.

Johnny Carson’s comedic style has gone out of style in the constellation of television shows offering comment on contemporary politics. The broadcast era economics that encouraged moderation in poking fun at political figures no longer make sense for satisfying the comedic cravings of small, ideologically slanted audiences. Seeking a return to Carson’s kingdom of gentler style, therefore, seems like misplaced nostalgia (and certainly not good business for network programmers). But this is discouraging. Are we now incapable of even laughing together at the politicians who need our collective approval to wield power?

How to audiences respond to 20th century comedic political commentary in 2022?

We suspect that though audiences gravitate toward comedic and/or opinion content based on expectations of ideological alignment with a host, this is not the same as proving that Carson’s comedic approach lacks appeal in this context. Carson’s approach to political comedy has various trademarks that distinguish it from much of what airs today. One example we found in Tonight Show transcripts included a reference to the nation’s overall welfare when dealing with contentious political events. Carson expressed this sentiment on his show at the height of the 1973 Watergate hearings (saying he thought that even Democrats would not want to impeach Richard Nixon because, in Carson’s words, “it would be terrible for the country.”) Carson made this point even while lobbing jokes about the 37th POTUS. Though a seemingly small gesture, we see Carson’s statement about impeachment’s potential national impact as a unifying perspective rare in contemporary political comedy. So how do people respond to it?

To find out, we conducted a vignette-based experiment using a national survey panel of 510 US adults in October 2016. Subjects received one of three vignette conditions featuring a joke attributed to the host of “a popular late-night talk show.” To avoid confounding effects, the treatments used no real names or show titles. Since ANES data show a stronger polarizing trend in Republicans’ presidential evaluations, we identified the unnamed president as a Republican to set up a more stringent test of a polarized subject response.

Our control material contained a modified version of a joke made about President Bill Clinton during his 1998/1999 impeachment, and was attributed to late night comedians (it was originally printed in the UK’s Guardian newspaper on 7 January 1999). It reads:

I was thinking about this, and if the president has proven himself to be a liar, he should be subject to a full impeachment inquiry before Congress. It’s his only chance of being tried before a jury of his peers.

The control made subjects aware the host offered a humorous statement about the president, but without the disparaging barbs. What we term the “Late Night” treatment—includes the control elements plus an overtly insulting late-night comedic approach: adding the words “liar,” “a morally corrupt, and ethically bankrupt idiot.” Most of these words were used in the Guardian’s 1999 joke (portending political humor’s coarsening trend). The third condition—the “Carson” treatment—featured a modified version of Carson’s 1973 words about Nixon’s possible impeachment (referenced above): “I don’t think even his enemies would want this because I think it would be terrible for the country.”

Photo by Possessed Photography on Unsplash

Modern audiences prefer Carson’s style

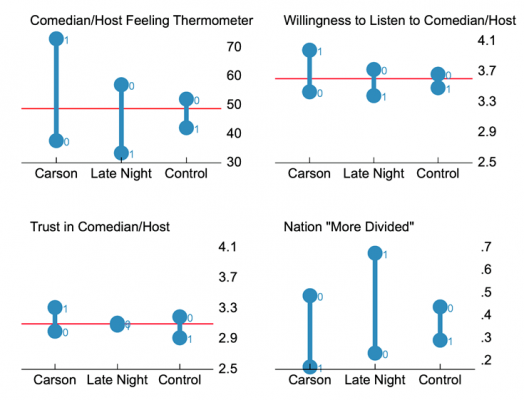

Our experiment has four main takeaways, shown in Figure 1. The first measure is a 0-100 feeling thermometer score for how positively or negatively subjects rate the host in their assigned stimuli. The second is a 1-7 scale on how willing subjects are to “listen” to the host (7 = “extremely willing”). The third is another 1-7 item for how likely subjects are to “trust” the host (7 = “extremely”). We find consistent statistical evidence that the subjects respond more favorably across these measures to the “Carson” condition compared to the “Late Night” or control stimuli (controlling for partisanship, race, age, and gender).

Figure 1 – Audience responses to ‘Carson’, ‘Late-night’, and Control vignettes

The fourth item focuses on polarization perception, and is a modified version of a commonly asked Pew survey question about whether the nation is “more divided” or “more united” politically over the last four years. Exposure to the “Carson” content in this measure statistically decreases the perception that the country is more divided.

Taken together, and whether current comedic programmers wish to take note, the Carson brand of political comedy clearly retains some of the broad audience appeal that made the King of Late Night a beloved television presence.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Nothing funnier than the news: Assessing Johnny Carson’s comedic effect, past and present’, in Social Science Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3uCccwM

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He has 50 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit and is the co-author of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (Temple University Press, 2013), A Matter of Discretion: The Political Behavior of Catholic Priests in the U.S. and Ireland (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), and Human Relations Commissions: Relieving Racial Tensions in the American City (2020 Columbia University Press).

Lori Han – Chapman University

Lori Han – Chapman University

Lori Cox Han is Professor of Political Science, Doy B. Henley Chair of American Presidential Studies and the Director of Presidential Studies Program at Chapman University. Her research and teaching expertise include the presidency, women and politics, media and politics, and political leadership.