In recent decades the US Congress has become increasingly polarized, with legislators taking increasingly more extreme ideological positions on various issues. But does this polarization reflect the US as a whole? Using data from the American National Election Study Helmut Norpoth and Michael S. Lewis-Beck find that the American electorate is far from polarized, with a plurality identifying with the political middle ground and a very small number considering themselves to be either extremely conservative or liberal.

In recent decades the US Congress has become increasingly polarized, with legislators taking increasingly more extreme ideological positions on various issues. But does this polarization reflect the US as a whole? Using data from the American National Election Study Helmut Norpoth and Michael S. Lewis-Beck find that the American electorate is far from polarized, with a plurality identifying with the political middle ground and a very small number considering themselves to be either extremely conservative or liberal.

Polarization has become the name of the game of American politics. The statement, ‘America is deeply polarized,’ sounds out every day in speeches by politicians and in the media coverage. Whether it is the Build-Back-Better agenda of the Biden administration or reactions to the January 6th attack on the Capitol, the drumbeat is constant and predictable: America is deeply, almost dangerously, split between two sides, with hardly anyone in the middle of the road. While that certainly describes the state of politics in the nation’s capital, does it hold true for the general population as well? We think not. In fact, for all the sound and fury, polarized politics in America frames a drama played out largely before an empty auditorium.

We can get some clarity about the meaning of the word by considering its use in basic chemistry, where the bond in a union of atoms shows attraction between particles of an opposite charge. Polarization, then, covers the state of attraction between these two, opposite poles, in this case opposite political ideologies— conservative versus liberal. If we assume members of the electorate hold an ideology then it can be described on a continuum from extreme liberal (on the far left) to extreme conservative (on the far right).

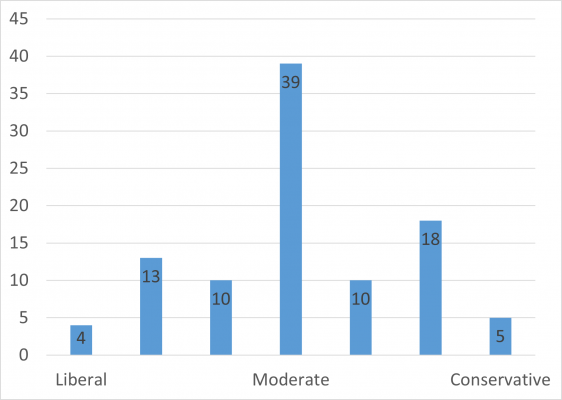

During the 2020 election campaign, the American National Election Study, widely considered the gold standard of election surveys, asked 8,268 randomly selected American citizens about their ideological location on the liberal-conservative spectrum, a question they have posed since 1972.The seven response options ranged from extremely liberal to extremely conservative with shades of each and a moderate option in between. The result: As Figure 1 shows, more than any other category, Americans in 2020 turned out to be moderate (or had no clue about the liberal-conservative spectrum). Barely a handful align with the endpoints, extreme liberal or extreme conservative. To be true to the meaning of the concept, polarization requires a bipolar distribution, as seen in the US Congress. That is certainly not currently the case for the American electorate.

Figure 1 – American Voters on the Ideological Spectrum in 2020 National Election Study

Granted, this rather benign finding flies in the face of the electric effect of then-President Trump and the heated exchanges during the 2020 election campaign. But it should come as no surprise to anyone following the American electorate over the past half century, as we noted with our colleagues William Jacoby and Herbert Weisberg in The American Voter Revisited.

Photo by Dan Dennis on Unsplash

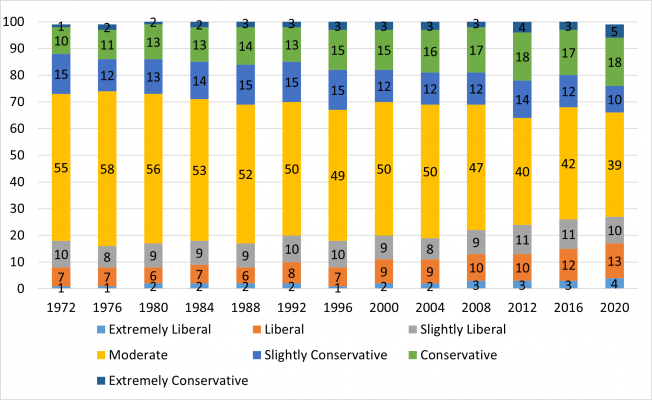

Ever since the National Election Studies started to query cross-sections of the public about this topic in 1972, most Americans have typically turned up at or near the middle, with less than a handful at the liberal or conservative endpoints, as Figure 2 shows. Just as they did in 2020. The ideological playbook has not markedly changed over the last half century. Polarization is a far cry, so far as the American electorate goes.

Figure 2 – American Voters on the Ideological Spectrum, 1972-2020 National Election Studies

Nonetheless we must acknowledge that some experts in the study of American politics, regardless of where they stand, see the United States electorate as “polarized.” They envision a polarization between two ideological factions fighting hard for their goals, separated by a wide chasm from each other – poles apart, in other words. James Campbell, for example, in his book Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America flatly says that “the American electorate is highly polarized….that most Americans are moderates….is a myth.” We admit that over the past 50 years the moderate mid-section of the electorate has shrunk, from 55 percent in 1972 to 39 percent in 2020 while the ideological extremes have widened their reach from a combined two percent to nine during that same span. But this is not a trend that supports the claim of sharp polarization in the electorate these days. We should remember that moderates still make up the largest group. Indeed, if the groups tagged, respectively, “slightly liberal” or “slightly conservative” are combined with the purely moderate group, we see they easily compose the majority of the electorate (e.g., in 59 percent in 2020).

But what about the polarizing effect of Donald Trump? The two elections in which he was on the ballot (2016 and 2020) witnessed an average share of four percent for extreme conservatives. That is hardly a noticeable increase over the 3.5 percent average for those groups in the two previous elections (2008 and 2012). Nor did Trump provoke a significant burst at the liberal end of the spectrum, with the average going from 2.5 to 3.5. However strongly he fired up his base and infuriated the base of the opposition, he failed to divide the American electorate into two irreconcilable ideological camps. Moderates remained the dominant camp during his tenure.

If there exists a “myth” here, it is not that most Americans are deeply polarized. They are not. Political scientist Morris Fiorina introduced that metaphor into the discussion of polarization with his provocative book (co-authored with Samuel Abrams and Jeremy Pope), Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America.

Like that study, our analysis of the liberal-conservative spectrum places polarization in the American electorate in the orbit of myth rather than fact. Clearly, when it comes down to policy positions on the fundamental liberal-conservative spectrum, the average American can more likely be found in the middle.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/36kFrur

About the authors

Helmut Norpoth – Stony Brook University

Helmut Norpoth – Stony Brook University

Helmut Norpoth is professor of political science at Stony Brook University. He is co-author of The American Voter Revisited and has published widely on topics of electoral behavior. His current research focuses on public opinion and elections in wartime.

Michael S. Lewis-Beck – University of Iowa

Michael S. Lewis-Beck – University of Iowa

Michael S. Lewis-Beck is F. Wendell Miller Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa. He has authored or co-authored over 300 articles and books, including Economics and Elections, The American Voter Revisited, French Presidential Elections, Forecasting Elections, The Austrian Voter and, Applied Regression.

Trump wasn’t the beginning of polarization. Bush was polarizing, Reagan was polarizing….according to the media. But Clinton and Obama weren’t.

But in reality those 2 Democrats were just as polarizing, but the right handled it differently, as a whole, than the left.

In essence, the media will tell us that the polarizing Presidents are those who don’t agree with them, and those Presidents who do agree with the media are not polarizing. It is alignment with the media that determines a polarizing President or not.

Most Americans don’t watch FNC, CNN, do not even have Twitter accounts. Go figure.