Most people in the US agree that American democracy is in danger, but there is little consensus on what that threat means. In their new book, Nicholas T. Davis, Kirby Goidel and Keith Gaddie look at why often populist threats against fail to mobilize a public that professes to believe in democracy. They argue that this lack of action may be down to the contested meanings of democracy and what it is for. For some, democracy is only about having free and fair elections and equal protection under the law, while for others, it is about reducing economic inequality and providing citizens with necessities. If we are serious about keeping American democracy alive, they write, direct appeals to save it will need to be explicit about how democracy is failing and how to fix it.

Most people in the US agree that American democracy is in danger, but there is little consensus on what that threat means. In their new book, Nicholas T. Davis, Kirby Goidel and Keith Gaddie look at why often populist threats against fail to mobilize a public that professes to believe in democracy. They argue that this lack of action may be down to the contested meanings of democracy and what it is for. For some, democracy is only about having free and fair elections and equal protection under the law, while for others, it is about reducing economic inequality and providing citizens with necessities. If we are serious about keeping American democracy alive, they write, direct appeals to save it will need to be explicit about how democracy is failing and how to fix it.

One of the most consistent findings in academic research is the existence of something called the principle-implementation gap. People can agree that an idea is perfectly reasonable but will largely reject any meaningful action designed to achieve it. It happens with government spending. People want government to create public goods such as law enforcement, healthcare, and national defense, but oppose new (or additional) taxes. It happens with climate change. The public largely accepts the idea that human-caused climate change is occurring but is unwilling to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels. And it happens with racial equality. People decry racism, but they reject policies that reduce inequality. It also happens, it turns out, with democracy. People claim to love democracy, but willingly sacrifice democratic norms in pursuit of partisan political ends.

A recent New York Times/Siena Poll illustrates this point. Most Americans (71 percent) said they believed American democracy was endangered, but there was little agreement on the nature of the threat or the appropriate corrective action. In response to an open-end question, the most frequently identified threat (mentioned by only 14 percent of respondents) was corruption, not the undermining of democratic norms or the rule of law by former President Donald Trump and the almost 300 Republican candidates running for public office in this year’s midterm elections who deny the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election.

Democracy on the ballot

Despite much weeping and gnashing of teeth about the “crisis of democracy,” a singular, widely shared understand of democracy is not on the ballot. Or, if it is on the ballot, it appears to be losing.

Why don’t right-wing populist threats against democracy inspire, mobilize, or persuade a public that professes to believe in democracy?

Our new book, Democracy’s Meanings: How the Public Thinks About Democracy and Why It Matters, suggests at least two reasons. First, according to open-ended responses, citizens mostly view democracy through the lens of “freedom” and “elections.” The United States is having an election this fall. It may be less free and less fair in some places than others, but, overall, the electoral apparatus in the United States hasn’t cracked apart – at least in the minds of ordinary voters who don’t pay much attention to the news or care much about the intricacies of electoral law.

But there is more to this development than an apparent lack of imagination. Citizens do have expectations about democracy and the sorts of conditions it ought to create, and they are not being met – something known as a democratic deficit. The problem is that when people talk about democracy, they aren’t always talking about the same thing. Indeed, they are often talking past one another, never fully agreeing on the essential characteristics that constitute democratic governance. Seen in this light, the current crisis of democracy is best defined, not by declining public support for democracy, but by contested meanings and, in turn, contestation over the civil and welfare “goods” that democracy is supposed to produce (or fails to produce).

“Democracy Going” by JmacPherson is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Saving which democracy?

Why does it matter those different definitions of democracy are floating around in the public sphere? Because if the meaning of democracy is contested rather than shared, appeals to “save” democracy will inevitably fall flat when people interpret such warnings differently. Save “which” democracy and from “whom?”

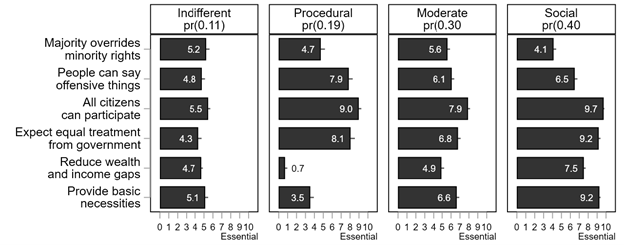

To better understand how the public understands democracy in our research, we made use of a series of survey items asking individuals about democracy’s essential characteristics. We include items that generate widespread public support (support for free and fair elections, rights to political participation, and equality before the law) as well as more controversial propositions (protections of offensive speech, providing the poor with basic economic necessities, and addressing economic inequality).

Rather than impose our own understanding of democracy on our survey respondents, we allowed public understandings of democracy to emerge from the data spontaneously, using machine learning to identify “clusters” of people who responded to these survey items in similar ways. That analysis uncovered four different groups that view democracy differently, none of which constitutes a majority of the American public (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Public Understanding of Democracy based on Latent Class Analysis

The most widely shared understanding of democracy is a social one, combining support for participation and equal treatment with reducing economic inequalities and providing citizens with basic necessities. According to our estimates, approximately 40 percent of Americans define democracy in these relatively expansive substantive terms.

At the other side of the continuum, however, approximately 20 percent of Americans understand democracy in minimalist terms. These procedural views of democracy extend to free and fair elections and equal protection of the law but reject the idea that democracies should address economic inequalities or provide for basic economic necessities.

A third group – moderates, for lack of a better term – sits between procedural and social democrats. Comprising roughly 30 percent of Americans, these Americans are less supportive of democratic processes than procedural democrats and less supportive of economic equality than substantive democrats. In this respect, their understanding of democracy is less well-grounded than substantive or procedural democrats. Finally, a fourth group is largely indifferent to the procedural mechanisms and substantive outcomes that define democracy. From a standpoint of supporting democracy, we should find them troubling, but they compromise just 10 percent of the population.

Why abstract calls to “save democracy” won’t work

The lack of shared understanding as to what constitutes democracy should give us pause when declaring that democracy is sliding into a “new” state of decay. The tensions that separate these meanings of democracy lie at the core of much democratic expansion and retrenchment. On a practical level, our research hints that support for political misbehavior varies across these groups: social views of democracy, for example, evaluate episodes of norm-breaking much more harshly than those with either moderate or procedural understandings of democracy.

For voters this fall, if democracy is on the ballot, as President Joe Biden recently proclaimed, then specific (and contested) visions that people hold for democracy will obscure campaign messages about saving it. Abstract appeals to democracy are neither a wedge issue nor a message that is necessarily attractive to the base. If voters see threats to democracy less in terms of concern about election legitimacy and more in the failure of democratic government to provide for the material well-being of democratic citizenries, direct political appeals based on threats to democracy must be explicit about what (and how) democracy is failing and how parties plan to fix it. Abstract calls to “save democracy” are insufficient if voters remain confused about what they are supposed to be saving.

- This article is based on the new book, Democracy’s Meanings: How the Public Thinks About Democracy and Why It Matters.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3zTBIQ0

As an academic who has researched and written about on saving democracy, this definitional essay is revelatory. Their work is a major contribution to the practical side of saving democracy.