Recent decades have seen declining intergenerational mobility in the US, though its pattern varies widely. In new research, Kohei Takeda unpacks the relationship between declining manufacturing in parts of the US – which are often termed the ‘Rust Belt’ – and workers’ income mobility. This mobility is affected by both falling labor mobility and the historic employment choices of people in former manufacturing centres. More education to break the persistence in these choices, he writes, may be the key to workers regaining intergenerational mobility.

Recent decades have seen declining intergenerational mobility in the US, though its pattern varies widely. In new research, Kohei Takeda unpacks the relationship between declining manufacturing in parts of the US – which are often termed the ‘Rust Belt’ – and workers’ income mobility. This mobility is affected by both falling labor mobility and the historic employment choices of people in former manufacturing centres. More education to break the persistence in these choices, he writes, may be the key to workers regaining intergenerational mobility.

The declining ability for Americans to increase their incomes across generations has attracted enormous interest in the US. Children from families in San Francisco have 8 percentile higher prospective income rank compared to those from Detroit in terms of their prospective income rank. Why, in the same country, are the citizens of San Jose or Tucson on entirely different trajectories than those in Detroit and Cleveland? The key to answering this question is the interplay between structural transformation in the aggregate and local economies in the US.

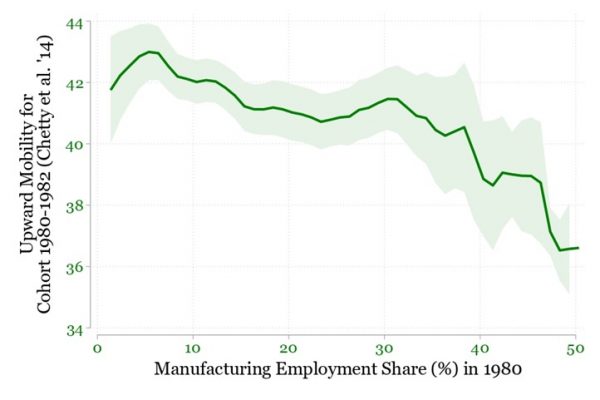

The last half-century has seen sustained deindustrialization and a general shift toward the service sector in the US. At the same time, there has been a significant variation in the rate of structural transformation across places in the US. Manufacturing employment share remains high in most cities in Rust Belt, while San Jose, El Paso and Plano, Texas have transformed into IT service sector hubs. The interesting question then is how these different rates of structural transformation actually translate into differences in upward mobility. Figure 1 shows the gradient between the rates of intergenerational income mobility and employment shares in the manufacturing sector for US cities. The main takeaway is that workers born in manufacturing cities in 1980-82 were less likely to achieve higher positions in the income distribution in the future. This observation is a prompt to look more closely at how the structure of economy across geography and time can influence patterns of intergenerational income mobility in different cities.

Figure 1 – Manufacturing Employment Share and Intergenerational Mobility in US Cities

Source: Takeda, 2022

How declining labor mobility affects income mobility

When one thinks about the term “Rust Belt”, which has been applied to many declining cities in the US, it is clear that there is an interaction between past economic activity and current income mobility. But, in these cities, why do workers miss out opportunities to move to productive locations, limiting their ability to increase their income? This leads our attention to two types of frictions – spatial frictions in location choices and inter-generational persistence in industry choices. First, in the US, people have been less mobile across geography. The internal migration rate in the US has fallen for more than three decades. This declining “geographical labor mobility” predicts less possibility of climbing up the location ladder. Second, differences in the composition of employment across cities can influence industry choices of workers over generations. Workers and their children in Detroit search for automobile industry jobs and are less likely to migrate to different cities since other cities have been losing such jobs as part of their structural transformation. On the other hand, workers and their children in Silicon Valley search for IT industry jobs and are more likely to migrate to cities where the number of such jobs is rising.

Photo by Javier Allegue Barros on Unsplash

Samples from the American Community Survey in 2011-15 show that the proportion of the cohort working in a particular industry is large when the industry’s employment share was large in their origin place. This tells us that an individual’s choice of industry is affected by the degree of structural transformation in the local economy. The combination of these two frictions – in migration and industry choice – can explain why citizens from different cities have different outcomes and why some remain mired in the Rust Belt with limited prospects.

How the decline in manufacturing has affected workers’ upward mobility

I examine this mechanism and, develop a framework to understand it and apply it to the experience of the US metropolitan areas during 1980-2010. The combination of the model and data illustrates how past exposure to different industries influences worker outcomes today, which creates the variation of intergenerational income mobility across cities. What would the geographic pattern of upward mobility be if structural transformation is slower than in the real world? My quantification shows that technological progress in the manufacturing sector accounted for around a seven percent decline in upward mobility for workers in the labor market in 2010 on average across cities. Beyond such aggregate effect, the spatial disparity in upward mobility would become small. Intuitively, slow structural transformation in such a counterfactual world helps workers from cities fall behind in the US because workers from the Rust Belt working in manufacturing jobs would have more opportunities for their jobs in the future.

What policy implications can we derive from the results? One potential answer to this is education in the local economy which can break the persistence in job choices over generations. My work shows that removing such exposure effects from where workers come from means that workers are more likely to go to productive locations and industries, with benefits for intergenerational income mobility. On average, introducing more education means that the degree of intergenerational income mobility increases by around four percent, and workers from cities suffering from structural transformation would benefit more.

My work helps explain how the structure of the spatial economy – through migration and local labor market exposures – shapes individual outcomes. There are several avenues for future research. Among others, the interaction between locations and the rapidly changing international market is perhaps the most interesting to look at. Globalization and in particular the US relationship with China is very much in the spotlight in terms of understanding why some cities in the US have prospered whilst others have declined. My findings can be extended to think about such backlash of globalization in terms of upward mobility.

We are at the first step to understanding how the US as a whole and not just a few cities within it can regain its place as a “land of opportunity”. This is fundamental to designing policies to equalize opportunities across locations within countries, something which is very much at the top of the policy agenda as the world gradually moves out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- This article is based on CEP Discussion Paper 1893, ‘The Geography of Structural Transformation: Effects on Inequality and Mobility’.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3l1xD7M