In January 2023, the United States government announced new enforcement measures at their borders to limit the entry of Cuban, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans into the country. Manuel Orozco argued in a recent report that those changes can reduce some but not all migration. It is very likely that people will keep trying to cross the border to overcome the severely harsh conditions in their home countries.

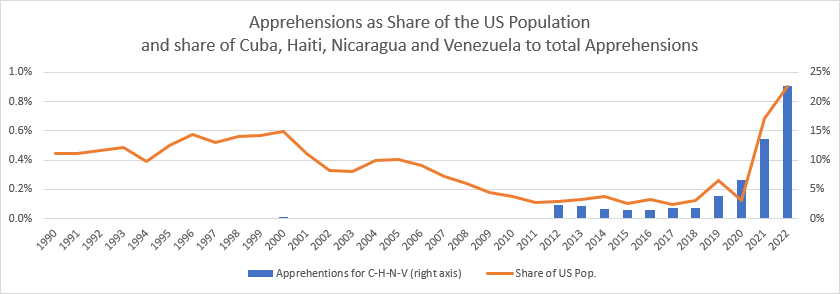

President Joe Biden’s recent border enforcement action is a partial solution to the real migration problem to better serve national security values and interests. The decision to limit the entry of Cuban, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans is an effective contradiction with US interests unless is not accompanied by more proactive foreign policy. It is unquestionable that a remarkably high inflow of migrants has shown unprecedented numbers equal to 1% of the US population. Also unquestionable is that such an increase is coming from the worst politically performing countries in the region: those countries the administration is targeting are almost 25% of all apprehensions in 2022 when in 2000 they were 0.3%.

The increase overlaps with the dramatic and worsening political conditions in those places: jailing, assassinations, censorship, fear, and corruption rule these countries. The United States needs a proportional foreign policy response to accompany these border enforcement actions; otherwise, people will continue to migrate. US policy in these countries must be proactive and as decisive as the values that protect democracy; that policy should be a strong reminder to citizens from these countries that they are not alone.

An inconsistent approach to reality

The change introduced may reduce some but not all migration. First, the measure may be marketing migration to those whose intention to migrate was not as strong as those with an urgent need to leave. Typically, half of those with an intention to migrate do not have a relative or someone known in the United States. The pool of US sponsors has grown small as those without legal status has increased in the past five years. Hence people petitioning may be smaller than calculated. Take Nicaragua as an example: according to official figures, there were less than 300,000 Nicaraguans in the United States in 2018, and about half of them had legal status, many of which with years in the US. As of the end of 2022, there were twice as many Nicaraguans in the US but in irregular status. Thus, those who may take advantage of the measure may not experience the urge to migrate. Our recent research shows that 16% of migrants in the US are legally admitted (citizens or legal permanent residents) and have a relative in Nicaragua with an intention to migrate, and another 20% are Nicaraguans legally admitted who know someone not related with an intention to migrate.

Second, the measure requiring having a US sponsor is problematic because it does not recognise that in most countries, the choice of coming to the United States is not because they know someone with legal status but because they feel safer in this country. People escaping worsening human rights violations are seeking safe haven first and foremost. This measure may dissuade some people from not taking the risk of being stopped and returned, but others may choose to do it knowing that there is a certainty of persecution back in their home country or that conditions will not improve. Citizens from the Northern Triangle continued to migrate despite the fact that Title 42 has been applied to nearly two-thirds of them: they have continued the trek because they see no future back home.

Apprehensions of Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan migrants in the US / Manuel Orozco

Apprehensions of Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan migrants in the US / Manuel Orozco

A proactive, consistent and comprehensive foreign policy response: the Nicaraguan case

Migration is a symptom of severely harsh conditions, and success should be measured by addressing violations of agreements and human rights and the effects on US interests. This approach can be accompanied and expanded with a more proactive, consistent US foreign policy than from last year with an effective commitment of resources proportional to US interests that can mitigate further political disaster and reduce migration. If the Biden-Harris Administration has made clear that “renewing democracy in the United States and around the world is essential to meeting the unprecedented challenges of our time,” then working proactively and consistently on these countries is an utmost urgency.

There should be two goals for the Administration; one is to restore confidence to citizens from these countries, emphasising that democracy is the only form of government and that they are not alone in this quest. The other is to figure out with these countries that a peaceful and negotiated solution is better for everyone than continued impunity, repression and economic downturn.

The US must take on leadership in promoting democracy (denouncing human rights abuses, defending civic engagement), and continuing the proportional and precise pressure (with sanctions, economic tools, and fight against censorship and disinformation). The country must take on multilateral partnerships, inclusive of the diaspora) to level the playing field towards political reforms and offer economic cooperation accompanied by political accommodation with civic forces.

The US policy on Nicaragua seems more complicated due to Daniel Ortega’s refusal to engage with the international community. But President Biden has the mandate of the Renacer Act, a formidable roadmap on how to deal with the dictatorship that is highly underused. It is important for the US government to focus its energies on strengthening a civic, democratic group that is both in exile and in Nicaragua but in a highly threatened environment. US policy should involve direct support to these groups, as well as provide tools to fight disinformation and censorship, so Nicaraguans are aware of their situation of the magnitude of kleptocracy. The US must open backchannels of engagement with dissident forces within the circle of power. These groups realised early on that Ortega’s route will take Nicaragua to a worse-off scenario than Venezuela, to ultimately reach a negotiated transition. Instead, they want to be instrumental but need assurances that they can be part of that political change.

Daniel Ortega has accused the US of instigating a coup, has used derogatory and racist terms against senior foreign policy officials, and implied that migration is a response to sanctions. However, the Biden administration has been a passive player while Ortega has violated the Central America Free Trade Agreement and the Democratic Charter, insulted US diplomats, expelled other representatives, used censorship and disinformation to campaign against the country, and signed military alliances with Russia. Compliance with Renacer Act is an urgent step given by Congress to act on conditions in Nicaragua.

Three caveats: sanctions, diasporas, and the OAS engagement

These differentiated steps need to consider leveraging sanctions, the diaspora and the Organization of American States engagement. Some think that sanctions serve a political behaviour modification role, but they are only a measure of accountability. The use of international sanctions is becoming widespread as an alternative method of accountability for those who violate human rights, commit international financial crimes, and avoid being held accountable in the judicial system. Sanctions should not be eliminated, but they should be aligned with precision, purpose, and proportional response to transgression in a non-cooperative environment.

Diaspora engagement is crucial to all these nations. The number of migrants arriving in the US from these countries amounts to nearly four million people. More than two million have arrived in the past five years and are the most concerned with what is going on in their homeland. The diaspora in each country has organised to mobilise resources to help their families through remittances but also to push US Congress to increase pressure on these governments. Including the diaspora in a dialogue over the political transition and rebuilding their homelands is an important step to foster dialogue as well as economic recovery.

Finally, the new US ambassador to the Organization of American States should include a regional approach in foreign policy leadership to rally support from the region’s partners and to promote political transitions that end political instability. It is important that the administration revives the normative elements of the OAS democratic charter in order to “stand together in defending against threats from autocracies.”

It is important to not give the impression that US policy to the region is avoiding upholding US interests vis-à-vis these dictatorships. Cuba, for example, has been repressing its population and using migration through Nicaragua to the US as part of an escape valve to deal with its failing economy. Similarly, other countries in Central America have learned from the Ortega regime and are liberally attacking the US and criminalising democracy. The US cannot politically and morally afford to have four Nicaraguas in the region. Instead, US leadership can restore faith in democracy.

- This blog post first appeared at the LSE Latin America and Caribbean blog.

- Banner image: Migrants wait at the border of the United States / David Peinado Romero (Shutterstock)

- Please read our comments policy before commenting

- Note: The post gives the views of its authors, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3IYZlKA