Risks from the US debt ceiling are more pronounced this year than they have been at any time since 2011 given heightened political polarisation alongside outstanding fiscal imbalances. Dennis Shen writes that even a potential last-minute avoidance of a technical default would still see the US economy sustain otherwise avoidable financial costs.

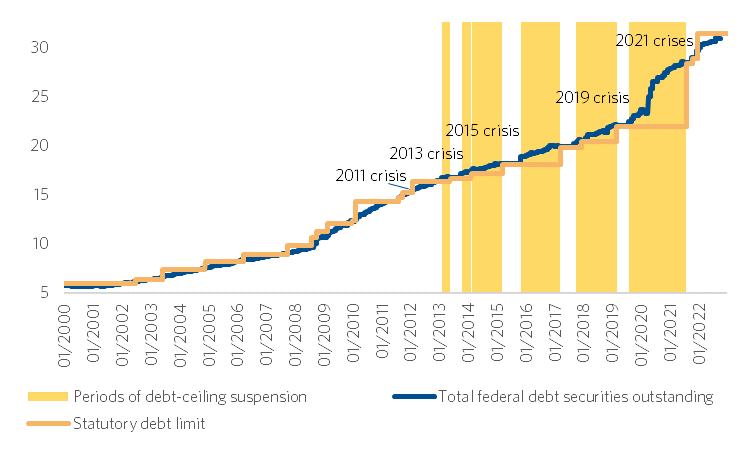

The US Treasury reached its debt limit of $31.4 trillion (Figure 1) on 19 January, prompting the Department to adopt extraordinary measures, such as deferring federal pension investments.

Figure 1 – Federal debt, $ trillion

Source: Congressional Budget Office, US Department of Treasury, Congressional Research Service, Scope Ratings

Unlike what some coverage of the debt-ceiling crisis consistently appears to argue, the United States has missed payments on its federal debt before. The most recent example of technical default (and the only example of the post-World War II era) was in 1979, which saw the US Treasury delay payments to investors redeeming Treasury bills at the same time Jimmy Carter’s administration was in a stand-off with Congress over the debt limit. So, commentators and analysts should not automatically assume debt-limit stalemates are inevitably resolved in the nick of time and without consequence.

Debt-ceiling crises are most perilous when a Democrat President faces a divided Congress

Debt-ceiling crises are most perilous when a Democratic President faces a divided Congress such as we have today. Political brinkmanship for securing political advantage can heighten during such times of divided government ahead of elections.

The federal government will most likely raise or suspend the debt ceiling at the 11th hour after agreement around some form of spending-curtailment programme later this year. Nevertheless, the risk around this debt-ceiling crisis is the highest it has been in a decade. Temporary non-repayment of the US’ debt could come via an ‘accidental’ default event following a miscalculation of the consequences of brinkmanship and the duration of political processes.

Debt-ceiling crises create otherwise avoidable financial costs

Each debt-ceiling crisis brings otherwise avoidable financial-market uncertainties, reduces the attractiveness of the United States as a destination for capital, and hikes operational expenses for markets.

According to the Government Accountability Office, delays in raising the debt ceiling back in 2011 hiked funding rates, elevating borrowing costs by $1.3 billion during the fiscal year. The Bipartisan Policy Center estimated that the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis, over a lengthier 10-year phase, raised borrowing costs by an aggregate $18.9 billion.

Photo by Emilio Takas on Unsplash

Some estimates suggest the unparalleled reputation of US treasuries as the leading global safe asset cuts the borrowing rate of the federal government by around 25 basis points (0.25 percent). Even if 10 basis points of this were permanently foregone because of a severe debt crisis, this may translate to lost interest savings for the general government of roughly $10 billion this year and $109 billion cumulatively over a five-year period.

The current US debt-ceiling crisis is also taking place as the status of the US as the issuer of the global reserve currency is slowly diminishing. The US dollar accounted for above 70 percent of global allocated reserves in the early 2000s. This figure had declined to below 60 percent by last year. This goes beyond short-run repercussions of debt-ceiling crises for the economy: the IMF expects moderation of economic growth to 1.4 percent in 2023 and 1.0 percent in 2024, after 2.1 percent last year.

A more severe debt crisis could further depress such macroeconomic projections. Goldman Sachs estimates damage to the economy of around $225 billion per month or 10 percent of annualised GDP if the Treasury were to stop other payments to ensure it continues to pay interest on debt this year.

Mitigating factors of debt crises and even of a technical-default scenario

Nevertheless, other factors could lessen the ultimate cost of debt-ceiling crises so long as a default is side-stepped. A halt in Treasury issuing bonds during debt-limit crises curtails treasury yields. Although debt-ceiling crises may raise borrowing costs long run, global safe-haven flows during peaks of such crises ironically drive inflows to treasuries in the short run, even if this undermines Federal Reserve objectives of quantitative tightening.

Even under an adverse scenario of a technical default, the US would presumably receive significant special treatment. When sovereign governments default, this is usually because of a severe lack of capacity to pay because of structural liquidity and/or solvency limitations. However, in the case of the United States, the capacity, and the willingness, to pay exist. The problem is a problematic political process and governance challenges.

The fact any default event for the United States would probably be temporary and would present minimal nominal losses for investors in the long run means the repercussions of default would likely prove much more benign than that experienced by other countries concerning effects for market access, borrowing rates, and financial stability. A ‘real default’ of the United States under a traditional sense of the term – involving much more substantive credit losses – remains highly unlikely.

Resolution of this debt-ceiling crisis anything but easy

But resolving this present impasse will prove anything but easy. The House (of Representatives) Rules Committee controls whether legislation around the debt ceiling goes to a vote. A single House Republican lawmaker can start the process for the House Speaker’s removal due to an agreement he co-signed earlier in the year. This might delay resolution of the crisis even after a suspension or raising of the debt ceiling holds a technical majority in the House.

Concepts like Treasury minting a collectible trillion-dollar platinum coin and depositing this at the Federal Reserve for cash and/or a proposal to invoke the 14th amendment of the Constitution are unlikely to be considered seriously except under worst-case scenarios. A seldom-used parliamentary manoeuvre known as a “discharge petition” to force a vote on raising the debt ceiling might be overly long and complicated for narrow spaces of time available in severe crisis.

No debt crisis in the US other than that of its own making

There is no debt crisis in the United States other than one of its own making. General government debt stood around 124 percent of GDP in 2022. But governments of Japan, Greece and Italy have even more elevated debt ratios.

Looking at the situation through a constructive lens, there are some scenarios under which this present crisis might support fiscal reform. That is if the crisis triggers reflection around budgetary prudence or it brings about reform or abolition of the debt ceiling. For instance, a bipartisan proposal from the House Problem Solvers Caucus seeks to set the debt limit at a fixed percentage of GDP.

Nevertheless, the history of debt-ceiling crises would not support the argument that such episodes having generally strengthened the quality of US fiscal policy.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3JUg1VD