There is a need to take stock of current global developments in the field of disarmament, reflect on the successful strategies that have been pursued and identify additional entry points to advance disarmament through international law. Louise Arimatsu and Keina Yoshida look at what a feminist approach to disarmament would look like, and how international law can be more effectively harnessed to further disarmament goals and peace, with commentary from the recent Women, Peace and Security (LSE) and Graduate Institute in Geneva co-hosted workshop.

The workshop “Women and Disarmament” marked a year since the UN Secretary General launched his disarmament agenda entitled “Securing Our Common Future”. Taking this as a backdrop, the workshop sought to foreground women’s activism around disarmament which has a long and rich history. This activism can be seen in activities from around the world including in the context of the UK in Greenham Common and by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). More recently, the ICAN project – which was inclusive and intersectional in its strategy and approach – won the Nobel Peace Prize for their campaign to ban nuclear weapons, which culminated in the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Women’s Activism and Disarmament

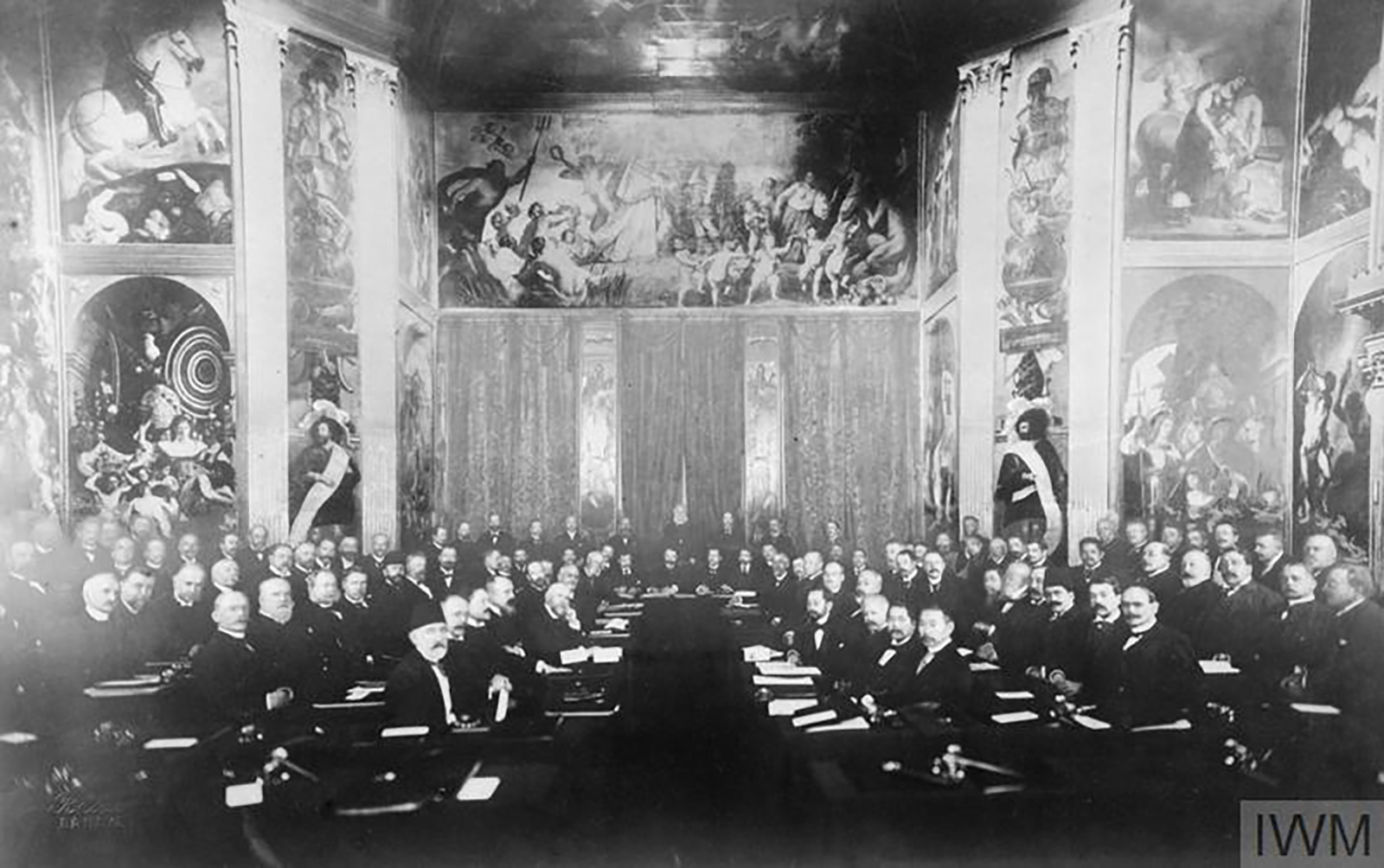

For over a century, women have played an active role in campaigning for disarmament including, most notably, through the work of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) which was established in 1915 amidst war. Committed to peace and undeterred by their exclusion from the public realm, the women who organised to advocate for peace and disarmament had to adopt creative strategies to be heard in the male-dominated world of inter-State politics. The story of disarmament itself has quite a short pedigree. The Hague Peace Conference of 1899 marked the first attempt by States to advance disarmament – or more specifically, arms limitation – through an international forum. No woman was among the 100 or so delegates who attended the conference.

Delegates to the first International Peace Conference, which was called by the Tsar of Russia to discuss world disarmament, The Hague, May – June 1899. Copyright: © IWM (HU 67224)

Although disarmament was designated a core objective of the League of Nations applicable to all Member States, in practice, it was a requirement imposed on the defeated States, a fact that was heavily criticised by WILPF throughout the inter-war years. It was during this period that the women of WILPF began to develop the conceptual foundations necessary to advance the core aims of conflict prevention and peace.

The adoption by WILPF of three parallel strategic objectives – universal and total disarmament (UTD); the dismantling of the private arms trade; and the prohibition of specific weapons systems – corresponded to prevailing views of the day, including among States. Members of the League were united in the belief that the pre-WWI arms race had created insecurity making war inevitable. This rationale was the basis for Article 8 of the Covenant of the League of Nations which held that the “maintenance of peace requires the reduction of national armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety” and the 1932 Disarmament Conference was an attempt to realise this ambition.

Committed to peace and undeterred by their exclusion from the public realm, the women who organised to advocate for peace and disarmament had to adopt creative strategies to be heard in the male-dominated world of inter-State politics

Women activists lost no time preparing for the conference. In 1931, the Disarmament Committee of the Women’s International Organizations comprising 14 women’s organisations (representing 56 states) dedicated to pacificism, was established. A petition with 12 million signatures supporting disarmament was delivered to the delegates, demonstrations organised, speeches made and books and newspaper articles published. Some of the strategies developed during those early years remain relevant today. Women peace activists have continued to build global partnerships; raise public awareness; produce expert analyses on disarmament; lobby governments; and organise non-violent direct action.

A WILPF member publicising the 1932 World Disarmament conference. LSE Library.

Challenges

Over the years, women’s activism has delivered some successes and historical records indicate that women have often been at the forefront of the disarmament debates.

That said, the escalation of the global arms race, the development and piloting of new weapons systems, and mounting pressure on existing treaty regimes raises questions over women’s activism and the future of feminist disarmament strategies. Paradoxically, one structural hurdle may reside in the UN Charter system itself which arguably takes a different approach to disarmament founded on the rationale that the inter-war arms race was a manifestation (or consequence) of the insecurity between states.

This is captured by the two core Charter principles: the prohibition on the use of force and respect for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all states. As typified by President Reagan’s remark “Nations do not mistrust each other because they are armed; they are armed because they mistrust each other”. This rationale shifts attention to addressing the security concerns of states and arguably functions to close down conversations around disarmament per se. A second hurdle concerns the ambiguity over the content and scope of what is meant by disarmament.

Women peace activists have continued to build global partnerships; raise public awareness; produce expert analyses on disarmament; lobby governments; and organise non-violent direct action

As feminist scholars, in collaboration with women activists, confront these conceptual challenges and seek through law and policy to give substance to the ambiguities that beset the disarmament discourse, it is worth recalling the words of Gertrud Baer, who, pondering on the lack of progress on disarmament in 1924 asked, “Did men say, ‘After you, sir’ as to disarmament?” and if so, “Let us women say, ‘Follow me’”.

This blog is based on a workshop co-hosted with the Graduate Institute in Geneva. It was written with the support of an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant and a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494).

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.