A decade ago, Dianne Otto identified the trouble at the heart of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda: the collision between the power of feminist ideas and the danger of cooptation and tokenism. The ‘power’ was not just that of an “imperial and hegemonic” Security Council which might act on behalf of a global women’s movement, but also of feminists themselves using the machinery of state. The ‘danger’ lay in those same institutions, where feminist ideas would likely be curtailed and distorted, the more radical elements jettisoned in favour of a veneer of legitimacy for the superpowers and the perpetuation of structures feminists otherwise criticised.

As we prepare to enter the third decade of WPS (formally inaugurated with the passage of resolution 1325 on 31 October 2000), the trouble persists. With ten Security Council Resolutions, the adoption of National Action Plans by 86 UN member states (as of August 2020), and a growing list of regional and supranational strategies (such as those issued by the EU, ASEAN and NATO), the WPS agenda is today a sprawling and varied policy architecture. It has been built on the work of social movements, civil society organisations, humanitarian agencies and others seeking to advance women’s participation, conflict prevention, protection and gender-sensitive relief and recovery. Importantly, this architecture can also be related to an increasing recognition by some states that a ‘feminist foreign policy’ would be in their national interest. It is not just that the ‘map’ of WPS is larger in the sense of including more states and international organisations. The terrain itself is also more varied, as ‘WPS’ has been applied to other policy domains and the meaning of key WPS terms interrogated by a new generation of scholars and activists.

In editing New Directions in Women, Peace and Security, we hoped to capture this dynamism, along several axes: the integration of new concerns into the agenda; the striking differences in where and how the agenda is implemented and experienced; the range of methods now used to map WPS, from participant ethnography to cross-national rankings; the ongoing dialogue between scholars, activists and practitioners (and the existence of ever more scholar-activist-practitioners), and the many critiques of the agenda’s foundational assumptions and practical limits. We are grateful to Aiko Holvikivi and Sarah Smith for their generous review, and to Toni Haastrup, Jamie Hagen and Nicole George for returning to the topics of their chapters. Other contributors to the collection reflect on their own encounters and scan the horizon of the agenda, addressing such issues as international criminal law, human trafficking, arms control and violent extremism in multiple sites, from foreign ministries to private military corporations and from parenting workshops to peace negotiations.

To take just two examples of the new horizons of the agenda, consider climate change and global health. As the effects of natural resource strain and catastrophic weather events become more common and more severe, displacement will become a reality for many more millions of people. As Briana Mawby and Anna Applebaum argue in their chapter, the gendered effects are likely to be devastating, not least for indigenous and poorer women in the global south. What can a WPS perspective on ‘disasters’ contribute in anticipating and mitigating these harms at a time where many states that champion WPS simultaneously adopt policies of asylum offshoring, remote control, and migrant ‘deterrence’?

With some exceptions, there has been little in the way of dialogue between global health governance and the WPS agenda (for example, it is not among the topics addressed in New Directions). The Covid-19 pandemic has brought many possible connections to the fore, from the gendered dangers of ‘home’ to the opportunity for a global ceasefire. But even before the pandemic, there were calls to ‘secure’ reproductive health through the vehicle of WPS. Just as was the case for activists in the run up to the passage of resolution 1325, the agenda offers openings to change the meaning and practice of security, even in the face of backlash and opportunism.

What can a WPS perspective on ‘disasters’ contribute in anticipating and mitigating these harms at a time where many states that champion WPS simultaneously adopt policies of asylum offshoring, remote control, and migrant ‘deterrence’?

Such horizons suggest that WPS continues to be meaningful in multiple contexts. The power of this agenda, evident in its growing acceptance in policy circles over the last two decades, also entails new intimations of danger. As many others have noted as well, the promise of a gendered peace may be accommodated in policies without challenging or transforming the arena of international peace and security. This is reflected, for instance, in the hierarchical arrangement of the ‘pillars’ of the agenda, with rights subordinated to a narrow reading of security.

Relatedly, formal policymaking is fraught with compromises; there is a fine line between gender mainstreaming and co-opting gender into business-as-usual, for example sustaining wars to protect women. This concern is raised a number of times in the book, including by sam cook and Louise Allen who highlight the need to protect ‘feminist spaces’ in these conversations. The challenge is to be heard by policymakers, but not at the cost of stifling critique or flattening diversity to ease consumption of ‘stories from the field’ and to make these more palatable.

Just as was the case for activists in the run up to the passage of resolution 1325, the agenda offers openings to change the meaning and practice of security, even in the face of backlash and opportunism.

There is an important material dimension to these challenges. In 2015, on the 15th anniversary of resolution 1325, the Global Study cautioned that “the failure to allocate sufficient resources and funds has been perhaps the most serious and persistent obstacle to the implementation” of the WPS agenda. With evermore humanitarian crises requiring international attention, funding for gender programmes continue to be scarce and irregular. In cases where funding is available, peace practitioners have to balance local necessities with donor interests.

A key set of contestations are located in the WPS agenda itself. Within civil society, this is apparent in the position on engagement with militaries or the hierarchies between well-networked experts and those doing everyday peacework in their communities; at the Security Council, this is reflected in the open debates. Some of these contentions go to the heart of international responses to the gendered dimensions of peace and conflict. For instance, advocates in at least some parts of the world remain sceptical of policies associated with the Security Council, in light of its institutional framework and history of selective interventions. Our collective work on WPS needs to inform and happen in conjunction with efforts to reform global institutions on peace and security, and secure sustainable peace.

In our introduction to New Directions, we set out a “critical cartography” of the agenda. The histories of the WPS agenda are histories of territorial struggle, not only over what the WPS agenda is (as discussed in the previous sections) but also over what is included as a “WPS issue” and what is not. We anticipate that the futures of the WPS agenda will be plural, but similarly contested, as a function of the complexity of the agenda. Sometimes, however, systems are defined by complexity. Further, as Anne Marie Goetz has commented, some dimensions of WPS

are next to impossible to quantify, such as the nature of engagement by women’s groups with peace negotiators and the quality of a transitional justice arrangement from a gender equality perspective. Indicators of these conflict-specific processes do exist. … [but] They are not intended to enable comparisons between cases of peace talks or recovery programs; each one is almost too anomalous to make comparative analysis meaningful.

Attempts to capture and even contain complexity brings into being a vision of WPS that has certain characteristics and qualities, shaping a world in which comparisons across diverse contexts can easily be summarised in numerical form. Such complexity is not easily tamed, however, and works actively against the desire to produce a more diverse WPS community, as Aiko and Sarah note.

We anticipate that the futures of the WPS agenda will be plural, but similarly contested, as a function of the complexity of the agenda. Sometimes, however, systems are defined by complexity.

‘Women, peace and security’ is the title of an agenda that can be used to realise women’s rights and to build just and sustainable peace. These are also the categories that we use to think with in the work we do towards peace, security, and gender equality, and we must not assume that any of these words have a singular or shared meaning. These are not, by themselves, liberatory concepts; each can be used in the gendered, racialised, and sexualised exercise of power which perpetuates hierarchies and structures of exclusion.

Answering questions about how to apprehend and understand intersecting dynamics of oppression and inequality, and acknowledging the differences and commonalities of women’s experiences of insecurity and violence across the world, demands the kind of thoughtful and inclusive analysis exemplified by the contributors to this collection. These are not easy questions. WPS advocates and defenders of women’s rights have worked hard to create opportunities for women’s meaningful political participation but we must also ask which women are able to participate, and whether diverse voices and perspectives are included, while simultaneously giving no quarter to those who wish to roll back the progress that has been so hard fought.

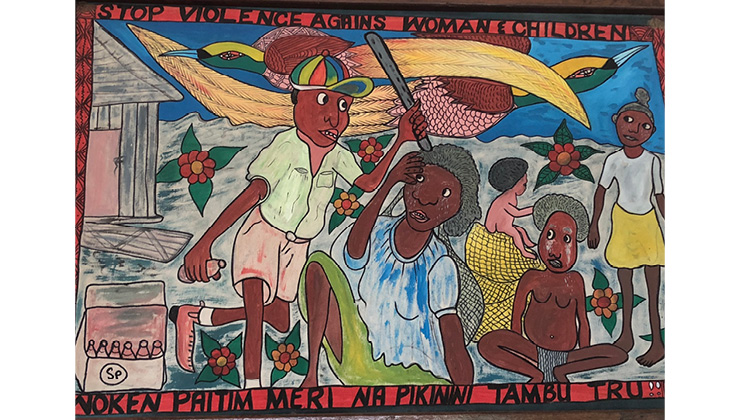

Image credit: Women, Peace and Security: Security Council Open Debate 2019. UN Women (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.