Deforestation has grown significantly during Jair Bolsonaro’s term by cutting funding, monitoring capacity, and enforcement rights from Brazil’s environmental agencies. But is his presidency the only one to be held accountable? Consumers, traders, and financiers have also profited from this, as Mairon G. Bastos Lima (Stockholm Environment Institute) and Karen da Costa (University of Gothenburg) analysed.

Leia este post em português

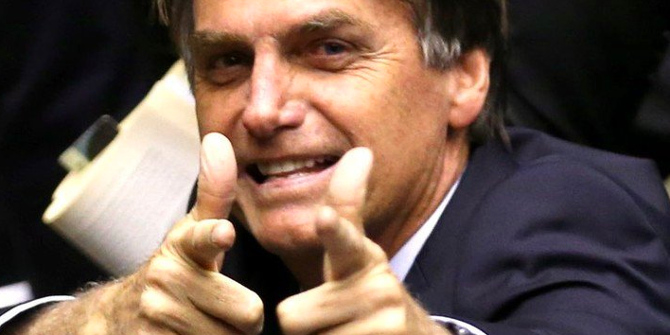

As Brazilians head to the polls in October 2022, there is the chance to either oust or re-elect President Jair Bolsonaro, a divisive figure that some have likened to a ‘tropical Trump’. Critics claim he is much worse. Whichever the outcome, there are important lessons the international community might draw from the past four years of the Bolsonaro administration in these times of climate breakdown. Not the least because global markets have connived and partaken in the plunder, even as the world allegedly unites in pursuing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

In a recent article, we analysed how the Bolsonaro administration has dealt with environmental sustainability. Brazil had reduced Amazon deforestation by 70% between 2004 and 2014, but yet again, it has spiked, reaching high levels not seen in more than 20 years. Indigenous peoples and other traditional communities have endured the most from what may seem like a hands-off policy. Since 2018, the year before Bolsonaro took office, invasions of Indigenous territories have tripled, usually for illegal logging or wildcat gold mining.

However, such an appearance of disregard may be misleading. We draw from ‘good governance’ literature as well as legal scholarship on nonfeasance (failure to perform an action required by law), misfeasance (improper performance), and malfeasance (intentionally harmful actions) to advance a differentiation between non-governance, misgovernance and malgovernance (see Figure 1), and to argue that what the Bolsonaro administration has done does not amount to non-governance or simple omission.

We examined two cases in detail: rising Amazon deforestation and how the government addressed an oil spill on Brazil’s Northeast coast in 2019. This was a serious environmental disaster, with thousands of tons of crude oil of unclear origin creating the largest petroleum accident in the country’s history. It was also the most severe environmental disaster in tropical coastal regions, killing countless marine wildlife and affecting millions who directly or indirectly depend on fishing. The causes of the disaster have remained disputed, and no one has answered for it.

Ricardo Salles, then environment minister, suggested on social media that Greenpeace could be to blame, saying it had a ship in international waters near that region at the time. The Federal government shut down the executive and support committees created in 2013 as part of the Contingency Plan for Oil Pollution Incidents to reduce public spending, and the cleaning up of the shore fell to individual volunteers exposing themselves to contaminants and to sub-national governments, whose actions were hindered by poor coordination and resource-sharing by federal agencies. We argue that was a clear case of misgovernance as a delayed and disorganised response amplified the disaster’s impacts.

Purposeful environmental destruction

We find that Amazon deforestation is a distinct matter. There, environmental destruction is purposeful, motivated by sheer economic interests and disregard for conservation or traditional populations. Through extensive document analysis, we reviewed tens of decisions, executive orders, and decrees whereby the Bolsonaro administration has cut funding, monitoring capacity, and enforcement rights from Brazil’s environmental agencies.

Although land-grabbing, agribusiness and mining interests had already been advancing over the Amazon, and its deforestation had been growing since 2014, it all became much worse under Bolsonaro. In a cabinet meeting in April 2020, later made public by Brazil’s Supreme Court, the environment minister overtly proposed using the opportunity that Covid-19 had diverted media attention to clear up environmental restrictions, away from public scrutiny.

That offers what could be a textbook case of malgovernance, which is at heart an ethical and political problem rather than a technical or merely managerial one. It has to do with actions that deliberately work against established goals and norms of an issue area. As such, on an international level, it cannot be addressed through standard forms of assistance such as aid or capacity building.

Brazilians will vote, but the international community is also empowered to deal with such cases, thanks to economic interdependencies.

Amazon deforestation is primarily driven by exploitative economic interests from sectors such as mining and agriculture, which receive foreign financing and depend at least in part on export markets. In other words, despite the professed Sustainable Development Goals, consumers, traders, and financiers have been complicit in Bolsonaro’s doings. Those players have not only failed to sanction environmental malgovernance in Brazil but also profited from it.

In such cases, noting it is not an issue of neglect, but of an economic agenda, the literature is clear that shifting incentive structures through conditionality – building on those international interdependencies – can successfully shift cost-benefit calculations. Political reform, whereby holders of state power engage with other stakeholders, does not happen if such powerholders continue to benefit unencumbered in international economic relations.

Our analysis draws lessons from the literature on South Africa’s apartheid regime to argue that, ultimately, it is only by empowering domestic adversarial coalitions that international actors can achieve sustained change. Therefore, it is about ceasing to condone Bolsonaro’s actions and supporting bottom-up change within Brazil. For malgovernance cannot be addressed by consorting with its perpetrators but only by tapping off their political and economic resources while making them more accountable to the societies they govern.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Storage yard with piles of wood logs legally extracted from an area of Brazilian Amazon rainforest / Tarcisio Schnaider (Shutterstock)