The Government of India’s recent move to increase maternity leave may have been a well-intentioned policy, but it has created a gap between costs to a company for male and female employees and reinforced traditional gender roles in childcare. Mitali Nikore analyses the weakness of the policy decision and makes recommendations on how it can be improved.

The Government of India’s recent move to increase maternity leave may have been a well-intentioned policy, but it has created a gap between costs to a company for male and female employees and reinforced traditional gender roles in childcare. Mitali Nikore analyses the weakness of the policy decision and makes recommendations on how it can be improved.

The Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Bill 2016 is being widely hailed as a historic step. The Amendment doubles the paid maternity leave entitlement from 12 to 26 weeks for all women in establishments with greater than 10 employees (with certain caveats, e.g. a woman with two or more children will only be entitled to 12 weeks, and the leave for adoption/children born through a surrogate is also reduced). It also mandates that crèche facilities should be provided within a prescribed distance, and women be allowed up to four visits a day to the crèche. The entire cost of these facilities must be borne by the employer. This article briefly discusses the likely impacts of this Amendment, presents an international comparison and then concludes with recommendations.

Impacts of the Amendment

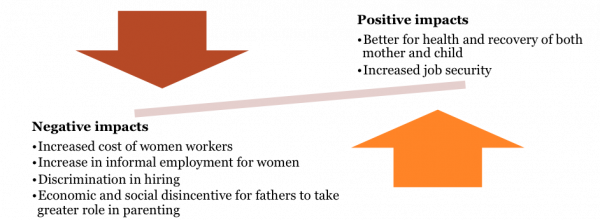

There are clear positive impacts of this policy for women’s health and well-being. Women getting longer paid leave, and consequently greater job security, is a positive development. However, the bill is likely to have certain unintended negative impacts, which could lead to a reduction in demand for female employees, particularly in the organised sector, as well as reverse recent gains which have been made in sharing the workload at home. Each of these are discussed below.

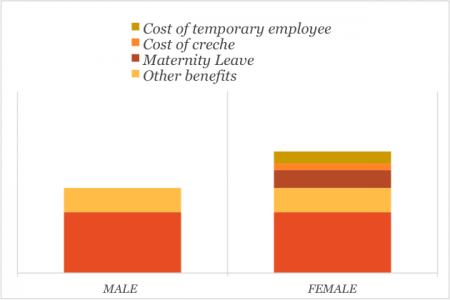

1. Increased cost of women workers => decrease in demand

The Amendment places the entire onus of the increased maternity leave, as well as of the cost of crèches on the employer. Now consider the choice of a prospective employer, especially if male and female candidates possess similar experience and educational qualifications. While the cost of hiring a male candidate would largely be restricted to salary and other statutory benefits, for women the incremental cost to company would now include the 26 weeks of paid maternity leave, cost of creating crèches, as well as the cost of a temporary employee who would need to be hired to fill the gap in the female employee’s absence of nearly six months.

Figure 1: Cost differential between prospective male and female employee

The likely consequences of this decision would mean a reduction in employment opportunities for women in the formal economy, as shown the figure below.

Figure 2:Impact of the increased benefits for women on employment opportunities

2. Maternity leave and crèches => placing the onus of parenthood solely on women

The statutory requirements in the Amendment reinforce the notion that the responsibility of child-care lies solely on women. The language demonstrates that lawmakers are completely alien to the concept of fatherhood, and cannot fathom a situation where 2 or 3 days a week, a child may go to a crèche located in the vicinity of the father’s workplace, and that the father may also want to have the facility of going and checking on his child at the crèche during the day. Therefore, by providing these ‘benefits’ of maternity leave, and crèches only to women, the law effectively places the onus of upbringing squarely on women, glorifying the ‘double-burden’ and ‘effective multitasking’ that they must undertake as men are not compensated for sharing the load at home.

International comparison

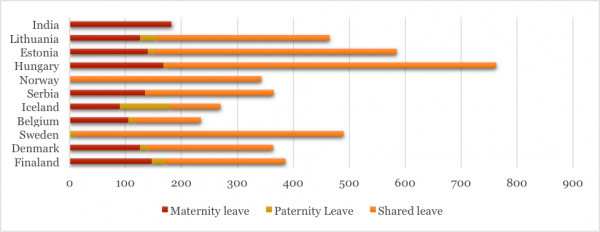

The International Labour Organisation recommends 14 weeks of maternity leave, while the World Health Organisation recommends 24 weeks. A comparison of India’s parental leave regime with the BRICS economies and with selected developed economies is presented in Figs. 3 and 4 below.

Figure 3: Parental leave in BRICS countries (days)

India is the only BRICS economy where there is no paternity or shared parental leave (which can be availed by either parent). Further, in each of the BRICS economies, barring India, the cost of maternity leave is borne by the government, through social security programmes, or rebates in federal or state taxes. Russia stands out as it allows almost 146 weeks of shared parental leave, although this is only partially paid.

A similar result is seen when comparing with selected developed economies identified by the World Economic Forum as having the best parental leave policies. Though India now offers one of the longest maternity leaves even amongst this group, unlike them, it places the cost entirely on the employer, and offers no paternity or parental leave, thereby increasing the cost of female labour to private sector.

Figure 4: Comparison with developed economies – parental leave (days)

Therefore, two key differences stand out when comparing the regulatory regime in India with the BRICS countries, or with developed economies:

Recommendations

While offering increased maternity leave may have been a well-intentioned policy, it has created a gap between costs to a company for male and female employees, as well as reinforced traditional gender roles in childcare. However, the situation can be remedied through any methodology which ensures greater parity in parental leave.

Following the example of Norway and Sweden, the distinction between maternity and paternity leave should be dropped, in the following manner:

- The law should entitle parents to shared leave, which can be split between a couple in the way they choose.

- While the onus of financing could continue to remain on employers, the respective employers of the couple should share the total cost of the parental leave, even if all the leave is availed by one spouse. The total cost should be calculated based on the wife’s annual earnings, as per the present law. For instance, assume that 26 weeks of paid parental leave is offered as per the law, and this is availed entirely by the wife. Then, even in that case, the husband’s company should bear 50% of the total cost of the leave.

In addition, firms should be mandated to create crèche facilities within a specified distance of their offices, and allow both male and female employees to visit their children during the day. The law needs to lead society in recognising that child-care is not the mother’s responsibility alone.

Conclusion

Currently the adverse impacts of the policy decision far outweigh the benefits, as women are likely to find themselves in a weak bargaining position. Increased parity in parental leave is a necessity to prevent women from being disadvantaged, and to ensure that there is a continued movement towards sharing the responsibilities of child-care.

Author’s note: This article has not accounted for the implications on single parents, particularly single fathers, or same-sex couples, as I do not find myself to be qualified to comment on their situation. However, given the reinforcement of gender norms in this law, I would imagine the detrimental impact would be magnified.

Cover image: Children play games at the mobile crèche. Credit: Overseas Development Institute CC BY-NC 2.0

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Mitali Nikore is a New Delhi based economist, focusing on urban infrastructure development and public private partnerships in the transport sector. She completed her Master’s degree in Economics at LSE in 2012, and has advised the United Nations, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and PricewaterhouseCoopers India.

Mitali Nikore is a New Delhi based economist, focusing on urban infrastructure development and public private partnerships in the transport sector. She completed her Master’s degree in Economics at LSE in 2012, and has advised the United Nations, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and PricewaterhouseCoopers India.

We already observe an adverse sex ratio in most organizations. This policy is expected to skew the curve further.

Amazing analysis showing the side effects of the current policy.

Perspectives are an eye opener. Very crisp and diagrammatic presentation of facts makes the article interesting.