In the mid-1990s nearly half of U.S. states adopted “three strikes” laws, which impose lengthy sentences after a third serious conviction, as part of a “tough on crime” policy approach. Many states, however, began to reform or modify these laws in the 2000s. In new research, Matthew Cravens and Andrew Karch find that states that use their three strikes laws regularly were less likely to reform them if they had more extensive prison privatization and organized prison officer unions. In addition, those states with a higher proportion of African-American residents were also less likely to modify their laws. While fiscal pressures and political ideology also influenced reform, the results suggest that stakeholders seeking to maintain an incarceration-heavy status quo had an outsized influence.

Between 1993 and 1995, twenty-four states adopted “Three Strikes and You’re Out” laws. The laws impose lengthy sentences on individuals convicted of a third serious crime, most commonly a mandatory life sentence without parole. Three Strikes laws epitomize the “tough on crime” approach that dominated criminal justice policy in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. During that time most new sentencing laws, like Three Strikes laws, reduced judicial discretion and imposed stricter penalties for several types of offenses.

In recent years, however, critics from across the political spectrum have questioned the wisdom of the “tough on crime” approach and lobbied for criminal justice reform. Three Strikes laws have been one of their targets. Several states have revisited their statutes, either sharply reducing the sentences for habitual offenders or giving judges more leeway during the sentencing process. Significant reforms have occurred in states like Indiana and South Carolina, while diverse states like Arkansas, Maryland, and North Dakota have left their laws intact. In our new research, we find that these reforms tended to occur when states that regularly used their three strikes laws had lower levels of prison privatization, lacked prison officer unionization, and had a smaller African-American population.

Developments in California, home of the defining battle over Three Strikes laws, illustrate the shifting politics of criminal justice policy. The state’s original law was adopted in 1994, a year after the kidnapping and murder of 12-year-old Polly Klaas by a convicted child molester with two previous kidnapping convictions sparked public outrage. Over the next 18 years, the law withstood several reform attempts. Finally, in 2012, California voters endorsed Proposition 36, which modified one of the most controversial aspects of the law by allowing life sentences to be imposed only after third “strike” convictions for serious or violent crimes. Two years later, California further altered its approach to sentencing by reclassifying several low-level drug offenses from felonies to misdemeanors.

The adoption and modification of Three Strikes laws offer powerful insights into current policymaking trends. By comparing the political forces that led to the rapid diffusion of the laws in the 1990s to those which facilitated or hindered their reform in the early 2000s, it is possible to identify how politics of criminal justice policy have changed over time. This sort of comparison offers several valuable lessons for those who wish to reform—or stop efforts to reform—state sentencing laws.

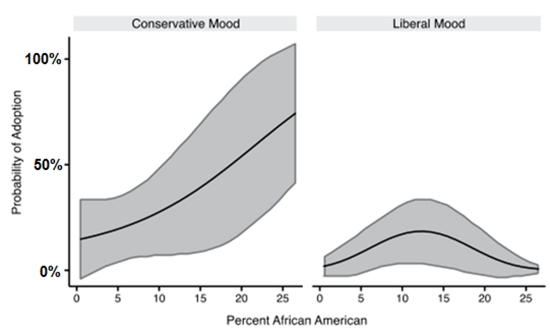

Three Strikes laws were motivated, in part, by harrowing stories of repeat offenders who committed violent crimes. However, states with high violent crime rates were no more or less likely than their peers to adopt the laws. The most powerful predictors of adoption were ideological and demographic factors. States with more conservative political leanings were significantly more likely to enact Three Strikes laws, especially as their proportion of African-American residents increased. This relationship is depicted visually in Figure 1. In addition, adoption was more likely to occur in states with a prison officers union. For example, the California prison officer union provided financial support for the signature drive that placed a Three Strikes measure on the ballot in 1994.

Figure 1 – Predicted probability of Three Strikes adoption

Notes: Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals.

In contrast, the modification of Three Strikes laws can be traced to a different set of factors. For instance, states were more likely to modify their laws if their neighbors had already done so. It is sometimes claimed that the recessions of the early and late 2000s motivated sentencing reform and, indeed, Three Strikes reform was more likely to occur in states in worse fiscal health. Ideology remained somewhat important, as conservative states were less likely to reform their policies, yet its impact was less pronounced than it had been during the wave of adoptions that occurred in the 1990s. The declining influence of ideology has occurred as some conservative groups have begun to push lawmakers to roll back strict sentencing policies.

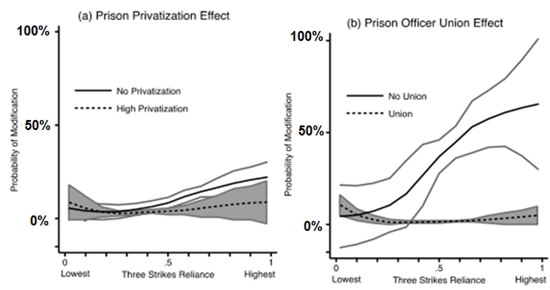

Three Strikes laws were used sparingly if at all in some states, while in other states they extended the sentences of thousands of offenders. This variability profoundly affected the prospects for reform, in part by affecting the mobilization of stakeholder groups. Private prison companies and prison officer unions have a strong financial interest in the adoption, expansion, and preservation of “tough on crime” policies like Three Strikes laws. Reform was especially unlikely to occur in states with high levels of prison privatization that relied heavily on the laws and in high-reliance states with prison officer unions. Figure 2 depicts these relationships visually. Affected stakeholders mobilized to preserve the status quo when and where they stood to gain the most from doing so.

Figure 2 – Predicted probability of Three Strikes modification

Notes: Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals. “Reliance” represents the number incarcerated under a state’s Three Strikes law.

Racial politics also affected Three Strikes reform, and its impact was felt especially strongly in states that used the laws regularly. Modification was less likely to occur in states that were more reliant on them and that had relatively high proportions of African-American residents.

In sum, the long-term trajectory of Three Strikes laws offers a window into the shifting politics of criminal justice policy and a hint of what might occur in the future. While some have speculated that recent reforms may be a temporary response to the fiscal pressures states faced during a recession, budgetary concerns are merely one of several important predictors of reform. In an era of heightened partisan polarization in the United States, sentencing reform is unusual because ideological divisions seem to be less important than they once were. The main obstacle to reform might not be the partisan divide. Instead, reform advocates may struggle to overcome the resistance of organizations that benefit financially from the imposition of incarceration-heavy policies.

If these stakeholders alter their positions or strategies, then comprehensive policy change might become a reality.

This article is based on “Rapid Diffusion and Policy Reform: The Adoption and Modification of Three Strikes Laws” in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Ken Teegardin (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1MB6rBW

_________________________________

Matthew Cravens – Dartmouth College

Matthew Cravens – Dartmouth College

Matthew Cravens is a Visiting Assistant Professor, Postdoctoral Fellow, and Manager of the Policy Research Shop at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center at Dartmouth College. His research addresses voter turnout, including how voting habits are formed and maintained, public policy, and the relationships between policies and public opinion.

_

Andrew Karch – University of Minnesota

Andrew Karch – University of Minnesota

Andrew Karch is Arleen C. Carlson Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. His research centers on the political determinants of public policy choices in the contemporary United States, with a particular focus on federalism and state politics. His most recent book, Early Start: Preschool Politics in the United States, was named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title of 2013. He is also the author of Democratic Laboratories: Policy Diffusion among the American States.

Thank you for the article. Prison corporations have high cell/bed quotas built into their contracts. We build ’em, and they fill ’em. For-profits are upside down. When they fail their jobs of rehabilitation and released prisoners commit new crime with new victims and are returned to prison, the for-profit, prison corporations increase their business and bottom lines. ‘A business model that is practically bankrupting states and wasting salvageable lives.