While experience can be an important part of being an effective politician, the average age of a US senator is 62; for the House it is 58. In new work, Matthew R. Haydon and James M. Curry look at why it matters if Congress is older than the rest of the country. Examining over 13,000 Congressional bills, they find that older lawmakers tend to introduce more bills that benefit older Americans, but get less media coverage, such as those concerning continuing education, elder abuse, and nursing home regulation. They warn that the attention given to these policies may potentially be at the cost of addressing issues with more importance to younger Americans.

While experience can be an important part of being an effective politician, the average age of a US senator is 62; for the House it is 58. In new work, Matthew R. Haydon and James M. Curry look at why it matters if Congress is older than the rest of the country. Examining over 13,000 Congressional bills, they find that older lawmakers tend to introduce more bills that benefit older Americans, but get less media coverage, such as those concerning continuing education, elder abuse, and nursing home regulation. They warn that the attention given to these policies may potentially be at the cost of addressing issues with more importance to younger Americans.

Everyone knows elected members of Congress are generally older than most other Americans, but it may surprise some to hear just how old. In 2015, the average senator was 62 with 40 percent of Senators aged 65 or older. The average House member was 58, with 26 percent at least 65. By comparison, 19 percent of Americans eligible to run for Congress are 65 or older, and while roughly one-third of the over-25 US population is under 40, in recent years less than 5 percent of our lawmakers have been.

Does it matter that Congress is older than the rest of the country? Observers often note a bias toward older Americans in the policies Congress enacts and supports, but attribute this to high levels of political participation among older Americans. Yet, as we argue in a new paper, that members of Congress are older may also contribute to Congress’s attentiveness to issues of importance to older Americans. Scholars have acknowledged that lawmakers’ identities influence their behavior.

The gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, and sexual orientation of lawmakers affects their attentiveness to issues, and their approach to the job. We argue that age matters, too.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

Looking at all bills introduced by members of Congress between 2005 and 2008 (the 109th and 110th congresses), we identified those that might be considered “senior issue” bills—those addressing policies or issues of particular importance to senior Americans. Out of over 13,000 bills introduced during this period, we identified 463 such bills. We then measured each lawmaker’s age at the start of each Congress, and the likely influence of senior citizens in each member’s district. (This latter factor is measured using an index combining the percent of each member’s district population over 65, and the average total monthly Social Security benefits distributed in each district). These two measures—a lawmaker’s age and his or her district’s senior power index—allow us to compare the relative influence of a lawmaker’s age and his or her senior constituents.

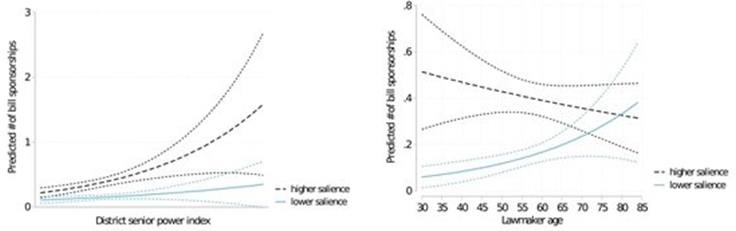

We find that both matter, but for different types of bills. Among highly important bills—those addressing issues receiving an above-the-median amount of attention in the New York Times—a member’s constituency matters the most. Lawmakers from districts with more “senior power” among their constituents introduce more highly-salient senior issue bills, such as bills addressing high profile policies, like Medicare. In contrast, lawmakers’ ages more strongly influence their propensities to introduce legislation addressing less-salient senior issues—federal policies affecting seniors, but that receive less media coverage—such as continuing education, elder abuse, and nursing home regulation.

Figure 1 – Predicting the number of higher- and lower-salience “senior issue” bills sponsored by members of Congress

We believe these findings to be intuitive. Lawmakers should be most motivated by constituent pressure on highly-salient issues. On these issues, engaged and mobilized seniors can spur members of Congress to be responsive. In contrast, on less salient senior issues constituent pressure is often muted, but older lawmakers will still be attentive because of a closer personal connection. This can explain patterns of issue positions taken by members of Congress that otherwise make little sense, such as octogenarian Senator Orrin Hatch’s (R-UT) leadership on and support for medical marijuana research, while remaining fairly conservative on other issues related to drug use.

So, it does matter that Congress is older than the country at-large. Since older members of Congress are more attentive to issues of importance to older Americans, the presence of a large number of seniors in the halls of Congress means it is collectively more attentive than it might otherwise be. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Seniors are a vulnerable population facing serious challenges, especially health-related. But the attention paid to those issues may come at the cost of attention paid to issues of importance to younger Americans. Whether it would be better for Congress to be more age-representative of the country at-large, we cannot say. But it would be different.

- A version of this article first appeared at LegBranch and is based on the paper, ‘Lawmaker Age, Issue Salience, and Senior Representation in Congress’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2t0ipkV

About the authors

Matthew R. Haydon – University of Utah

Matthew R. Haydon is a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah.

James M Curry – University of Utah

James M Curry – University of Utah

James M Curry is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Utah, and co-director of the Utah Chapter of the Scholars Strategy Network.