Ollie Cook is in LSE’s International History department and in a previous post, he wrote about his plans to be part of the first crew to row down the Zambezi. He’s back from a successful trip with Row Zambezi which raised funds and awareness for the charity, Village Water.

On 14 August we rowed past the Livingstone Boat Club to the sound of the local marimba band, an escort from a press boat and the local jet boat, finishing a 1,000km row down the Zambezi from Chavuma on the Angolan border to Victoria Falls. It was the first time anyone had rowed the Upper Zambezi, during which we dodged hippos, skirted the borders of four countries, raced crocodiles, were entertained by the Lozi king (Litunga) in Barotseland, and enjoyed the immense hospitality of the Zambian people.

Scottish explorer David Livingstone’s famous quote “I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it is forward” was given new meaning when we pushed off in Chavuma on 27 July to row 1,000km backwards. We began the Row Zambezi expedition less than 2km from the Angola border with the blessing of the local District Commissioner and some rather bewildered villagers.

We had our first encounter with a crocodile on the second stage of our journey from Chinyingi mission to Lukulu. After rowing to one side of the river to avoid a pod of hippos we caught sight of the local “Kwena” (Lozi for crocodile).

We stopped to have a good look at him and he suddenly swung his body out of his midday sunbath and slid into the Zambezi. The immediate realisation that he was somewhere in the dark water around us was not lost on any of us. I particularly felt for the Zambian rower in my boat who was wearing a life jacket because he couldn’t swim. He went into overdrive and didn’t stop rowing until we were 20km away from that first sighting.

The Zambezi is truly magnificent. It moves quietly as one immense handsome force pushing itself effortlessly through the Zambian bush. Apart from the groan of the hippos and the flashes of brilliant blue and gold of the pygmy kingfishers, the bush gives no clues that such a beautiful river lies within it.

The next stage of our row was the Barotse floodplain, home to the Lozi Kingdom. The Barotse is a huge floodplain and during the rainy season the Zambezi sometimes swells up to 25km wide.

On the first day of the Barotse, Row Zambezi had its closest encounter with a hippo. The engine on the support boat had developed an annoying habit of suddenly stopping and refusing to start as if it sensed danger ahead. It would only start again with some gentle reassurances and not so gentle pulls on the starter cord.

In the middle of the river the engine stuttered and died. While we were attempting to bring the engine back to life, we floated to one side of the river. It was then that someone noticed a trace of bubbles two meters from the boat. It seemed as if a submarine was slowly emerging from the Zambezi, water gushing off its dark head. Rather, it was a hippo that surfaced. We frantically tried to jerk the engine back to life with the hippo eyeing us suspiciously. After what felt like a lifetime, the engine kicked and we took off leaving our inquisitive encounter in a flood of water.

The fleeting greeting with the hippo on the first day of the mini expedition was the only anxious moment during the Barotse. Camping on the sandy banks of the Zambezi every evening, eating Ministry of Defence (MoD) issue ration packs and supplementing them with bream and tiger fish bought from the locals were some of my favorite moments of the expedition.

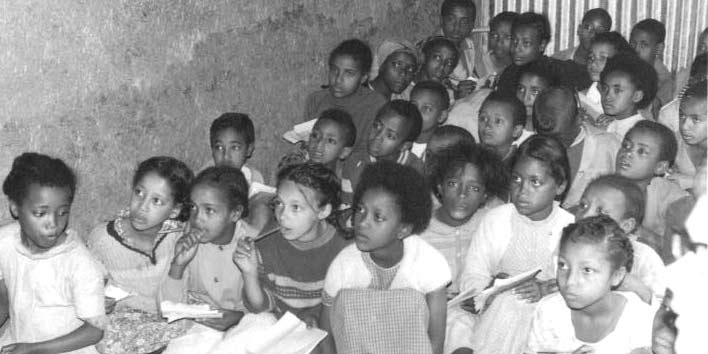

We were totally taken by surprise by the extent to which the Zambezi is used by local Zambians. During the day we were greeted by running children with entire villages coming out to see us. All through the night fishermen balancing on their mokoros would entice fish to the surface using lanterns while beating the water to ward off crocodiles. The Zambezi is truly a highway for the local communities. We were also surprised to hear music from distant villages every night we were in the Barotse. Our Zambian guide was keen to point out that “every night is party night in Zambia”.

The Litunga (king) Lubosi II of Barotseland and head of the Lozi tribe had heard about the expedition and wanted to meet us. His palace is situated five miles outside Mongu, the capital of the Western Province. Set in a walled hamlet of colonial-era buildings, the immense reverence the Lozi hold for their Litunga was immediately evident. While waiting for the king, we watched while a member of the Acuta (the Council of Elders of the Lozi tribe) painstakingly crawled up to the Litunga’s Lubona (throne), placed a box of tissues by its side and retreated clapping and bowing his head towards the chair. During the meeting we were shown the two huge drums that are carried as part of the infamous Ku omboka festival.

The Ku omboka means “coming out of the water” and is an annual festival that marks the beginning of the rainy season. It marks the movement of the Lozi tribe from the floodplain of the Barotse to higher ground. The Litunga traditionally has two capitals, his summer one on the banks of the Zambezi near Lyalui and one during the peak of the rainy season in Mongu.

We were invited to the ku kambama which means to “climb to a higher level”. This referred to the great honour of being in the presence of the Litunga. We presented our gifts, which included some Ormonde Jayne perfume (for the king and his wife) and the latest google maps of the Barotse floodplain.

The Litunga addressed us in person instead of speaking through someone else, which, according to the Zambians among us, was incredibly rare. He said that he was privileged to host us on our expedition, and expressed his admiration that through rowing we were able to enjoy the river without spoiling it. He talked about his love of water sports and even hinted that if there was another rowing expedition he may be tempted to get involved!

He then posed for photos which shocked the Lozi Council of Elders, and spoke personally to each one of us. After telling him that I was a student at LSE he told me he had studied at UCL (he called it studying at Russell Square) and that he had attended some public lectures at LSE!

While in the Mongu area, we also visited the headquarters of Village Water, the charity for whom Row Zambezi is raising money and awareness. We also saw their latest project in Lukolo village where work has started on a water well. It was fantastic to see first hand the transformation Village Water is delivering to this remote community.

The final stage of the expedition from Senanga, on the southern tip of the Barotse, to Victoria Falls would take us past the border of three countries, see us skirt four major game reserves as we contended with the tenacity of the Zambezi rapids, including Sioma Falls.

The heart of the rapids spanned almost 300 metres, and was dotted by a plethora of channels. We had heard that the belly of the rapids contained a number of standing waves. It was quite frankly unrowable.

We decided to float the boats through the channels then take them out and carry them 1.5km around the rapids. The water was initially so shallow it barely covered our feet, we therefore had four rowers float each boat over the rocks before the opening of the channel.

As we approached the channel, the depth of the water suddenly dropped and the speed of the water picked up greatly as the water was squeezed through the narrow passage. The lead boat got swept into the channel with the rowers desperately clinging on. The sky abruptly disappeared as the overhanging trees and bushes enveloped us.

With only an eerie green light coming through the canopy, the boats got stuck on roots and branches blocking the channel. Out came the machetes and knifes as we hacked our way through the Zambezi. Tilly hats on, it looked like something out of a Vietnam movie as we swam the boats through the channels grinning from ear to ear.

We made it out the other side, covered in tiny leeches and with one of the support boats ripped, but we felt like we had finally tasted what it may have been like for Livingstone 150 years ago, leading an expedition without the maps and equipment that we were relying on.

We finished the row on 14 August, my Dad’s fiftieth birthday, arriving to a beautiful reception at the Livingstone Boat Club. The expedition finished almost as quickly as it had started. It had been 20 days since we left Lusaka and it was suddenly over. We had made it, 1,000km from the border with Angola to within sighe of the mighty columns of steam rising from the Mosi-oa-Tunya.

I stayed in Zambia for two weeks longer than the rest of the expedition to do some research for my dissertation on David Livingstone and the role of the Victorian media. I visited the Livingstone Museum in Livingstone town and met the director, a very nice quiet man called Vincent Katanekwa.

Although the Museum’s resident historian, Dr Friday Mufuzi, was away, he allowed me to access their David Livingstone archives. The first thing I pulled out was a letter Livingstone had written to his nephew Neil, dated 20 July 1863.

Here I was actually touching a real letter, a bluish grey piece of paper that David Livingstone had written on the shores of Lake Nyasa. I don’t know if Vincent knew I was only a second year undergraduate but I wasn’t going to enlighten him!

Vincent left me to look through the folders containing Livingstone’s correspondence and various other documents, such as Livingstone’s first sketches and measurements of Victoria Falls. I was aware that I was handling an incredible collection of material, but over time the documents had become jumbled and some were clearly deteriorating.

I spent the rest of my time at the Museum working with a kind and gently-spoken researcher called Kingsley. We made a note of all the material, who Livingstone was writing to and the date and year he wrote it and organised it as such. We weren’t able to finish but hopefully it is in some order which might make the process of digitalising it easier one day.

I had a truly amazing time in the five weeks I spent in Zambia. There had been some rather edgy moments, including the encounter with the hippo in the Barotse and the swim through the Kasanga rapids. There had also been some moments that had taken my breath away. Camping on the banks of the Zambezi, watching the sun go down to the groan of hippos, with the rich golden glow of the river reflecting the sinking sun while we sipped a cheeky beer or two that we had sneaked into our ‘emergency rations’. Not to mention meeting the Litunga of the Lozi tribe, seeing the work of Village Water and helping at the Livingstone Museum. But above all it was the kindness and warm-heartedness of the Zambian people, who time and again went out of their way to help us, that I will most keenly remember.