LSE’s Atta Addo calls Africa’s Peacemakers: Nobel Laureates of African Descent an illuminating and well-researched volume which, despite a lack of a strong central concept, should be read by all those interested in Nobel Peace Prize winners of African descent.

Adekeye Adebajo, Executive Director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, South Africa, and author of works such as The Curse of Berlin: Africa After the Cold War and Building Peace in West Africa, has assembled an impressive list of fourteen expert African and African-American contributors — a mix of scholars and practitioners—to write for this illuminating and well-researched volume. The book, dedicated to the memory of perhaps Africa’s most esteemed Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (18 July 1918- 5 December 2013), is a collection of abridged biographical essays on the thirteen African and African-American winners of the Nobel Peace Prize. The collection is an attempt to, in the words of Adebajo, “draw lessons for peacemaking, civil rights, socio-economic justice, environmental protection, nuclear disarmament and women’s rights” against a backdrop of what eminent Kenyan scholar, Ali Mazrui has called Pax Africana (an African-owned peace) (p.4).

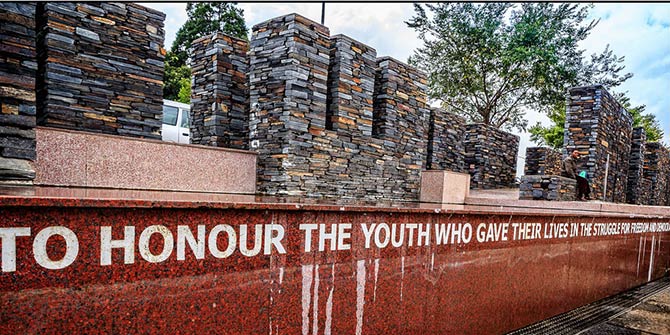

The thirteen winners whose stories are told have championed nonviolence and human rights and fought oppression in various spheres and contexts. They include, in chronological order of winning: Ralph Bunche (1950) for having arranged a cease-fire between Israelis and Arabs during the war which followed the creation of the state of Israel in 1948; Albert John Luthuli (1960) who won as leader of the African National Congress (ANC) for its non-violent resistance again apartheid; Martin Luther King Jr. (1964) for combatting racial inequality through nonviolence; Anwar Sadat (1977), joint winner with Menachem Begin of Israel for their contributions to peace in the Middle East; Desmond Tutu (1984) for his role as a unifying force in black South Africa’s non-violent struggle for liberation; Nelson Mandela and Frederik Willem de Klerk (1993) for their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundation for a new democratic South Africa; Kofi Annan (joint winner with UN, 2001) for his work for a better organized and more peaceful world; Wangari Maathai (2004) for her contribution to sustainable development that embraces democracy, human rights and women’s rights; Mohammed El Baradei (2005), joint winner with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for efforts in support of nuclear disarmament and world peace; Barack Hussein Obama (2009) for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples; Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Neyma Gbowee (2011) for their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.

The book’s fifteen chapters are organised into six parts with two introductory chapters—the first connects the themes and presents the thirteen winners, and the second frames the collection in the context of Barack Obama’s award and its relation to the other winners of African descent and most importantly to Mahatma Ghandi, a beacon in the global nonviolence movement who astonishingly was never awarded the Prize due to political reasons. Part two assesses the three African-American laureates: Ralph Bunche, Martin Luther King Jr. and Barack Obama and articulates their comparative perspectives on war and peace. In part three, the anti-apartheid efforts of four South Africans, Albert Luthuli, Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, are outlined and evaluated. Part four discusses the contributions of the Egyptian winners, Anwar Sadat and Mohamed El-Baradei while part five discusses the work of Kenyan environmentalist, Wangari Maathai and Ghanaian former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan. The final chapter features the stories of two Liberian women winners, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Leymah Gbowee who fought for women’s and civil rights.

Despite the book’s laudable attempt to interweave disparate biographical narratives into related themes such as the struggle for peace, justice and freedom, as well as intriguing comparisons that are not immediately obvious, a possible drawback remains the lack of a strong central thesis to carry the narratives through. As such, it is unclear why the stories of these thirteen Nobel Peace Price winners—taken together—should matter to the reader, especially against a premise of their connection to Africa. To be fair, the problematisation of Africa’s connection to the Nobel Peace Prize or to world peace and human rights generally is not an easy task, and the book makes a good effort, but nonetheless, struggles. It is clear from the outset that the discussion is not simply about black race and the Nobel Peace Prize as one might wrongly deduce from the title, given that not all the laureates discussed are racially black. This creates a grave issue to be resolved, namely, how Africa and African descent are imagined by the authors. Eminent Kenyan historian, Ali Mazrui, takes up this discussion in his submission on Barack Obama (Chapter 2) and makes the following claim:

[…] let us now deal with the distinction between ‘Africans of the blood’ and ‘Africans of the soil’, Africans of the blood belong to the black race; Africans of the soil belong to the African continent, but are not necessarily of the black race […] Most Egyptians are not immigrants, and are therefore Africans of the soil by adoption. Ghanaians and Nigerians are, in reality, both Africans of the blood (as black people) and Africans of the soil (as children of Africa). On the other hand, diaspora black people, such as Barack Obama and Toni Morrison, are Africans of the blood (racially black), but are no longer Africans of the soil […] (p.47)

While Mazrui’s distinctions above may be convenient for summarily categorising personalities with strikingly dissimilar backgrounds, and for justifying the Africa nexus that is so central to the book, it evades the bigger question of how Africa per se, however imagined, is substantively implicated in the pursuit of peace and human rights generally, and the Nobel Peace Prize specifically, either on some deeper empirical or conceptual level. The result is that while the book wilfully resists becoming a hagiography of these unquestionably accomplished personalities (p.10), it struggles to be much more else even though it is sometimes critical – for example, questioning the award of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf despite her ambiguous role in the Liberian civil war between 1989-1997, and criticising the joint award of Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk as well as the failure by the Nobel Committee to ever award Mahatma Ghandi due to political clout of Britain. Consequently, one might be tempted to read the volume as a whole as an apologetic—a sort of justificatory enterprise, albeit not a self-conscious one—for a largely uncontested thesis that people of African descent have also contributed to world peace and human rights and have been recognized by no less than the Nobel Prize (in the trope of black magazine narratives with titles like ‘The Top Ten African/Black X You Have Never Heard of’, where X may be something positive Africans/Blacks are somehow presumed to seldom accomplish).

For its inconsideration of a unifying conceptual or theoretical concern, the stories cannot be considered as case studies per se. Hence, it is unclear how the book achieves its objectives of drawing lessons for peacemaking, civil rights, socio-economic justice, environmental protection, nuclear disarmament and women’s rights. Nonetheless, this book is to be read widely by all those interested in the Nobel Peace Prize winners of African descent, either for its own sake or for better appreciating the varying shades of anti-violence struggles against oppression, injustice and human rights violations that these eminent people have championed.

Africa’s Peacemakers: Nobel Laureates of African Decent

Edited by Adekeye Adebajo

Zed Books Ltd, 2014, 330pp., £14.99, ISBN 978-1-780332-943-7