LSE’s Alice Evans checks her privilege as she recounts some of the not-so-pleasant aspects of her fieldwork.

I shouted fiercely, telling him to back off. Instead he persisted, mirroring my lurches left and right – as if we were playing football together. But it didn’t feel like a game. He was drunk and backing me into a corner. Taunting me. Scared, I darted out into the woods behind, leaping round the thicket, escaping into the safety of the cooking hut – a female domain. Breathing quick and fast, frightened.

There were other unpleasant incidents as well. Both of those times I was wearing a citenge – a long wrap skirt (a symbol of female respectability in Zambia). Both times I shouted back, in Bemba. The acts themselves did not trouble me. What was exhausting was the constant vigilance – especially when amid crowds of unknown, unemployed young men. Maybe it was something about power: trying to assert their domination over a symbol of the West, otherwise outside their grasp.

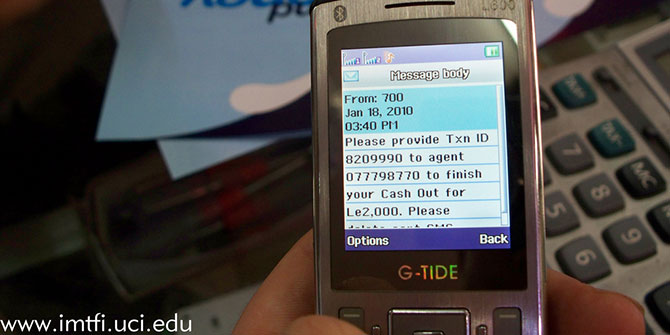

Power was also exercised by those accustomed to having their way, such as the deputy minister (and church elder) who sent the following text: “So will take a bigger room for two people so dont book whn you come”. Sternly, I told him I would need my own room and that it was highly inappropriate for him to say anything like that.

The emotional toll of such disrespect paled in comparison to the stress of travelling. Obstacles included the Congolese border officials who sought to intimidate me, in the hope of making a little extra money to supplement their meagre incomes. They interrogated me first in Bemba and then in French, assuming I spoke neither… There was also the bus that needed to be dug out after toppling over on a dirt track, deep in the Congolese bush.

Oh, and then there was the time I woke up unable to open my eyes. Much as I strained my eyelids, they refused to budge. Cemented together by dried yellow gunk. Easily fixed though. Asked advice from my friend, a senior doctor. Promptly went to the chemist in town, bought eye drops for conjunctivitis. Thank heavens I wasn’t back in the village: two hours walk from the nearest clinic – often poorly stocked.

Indeed, each of these ‘hurdles’ were entirely navigable. The deputy minister thought I might cede to his advances in gratitude for free accommodation – as many others might in a context of over 40% youth unemployment in Zambia. The harasser mentioned in the opening paragraph (a secondary school teacher) was similarly used to getting his way. It was no secret that he had many girlfriends (mostly school girls, whom he bought little treats) and failed to provide for his wife. ‘Not even a citenge to carry her child on her back’ [translated], bemoaned one villager when I relayed the tale.

Money helped a lot – especially when travelling through DR Congo. Moreover, all I needed was cash. Contrast that fortune with difficulty of procuring a UK visa.

I had also lucked out on the birth lottery. While I worked at an institution with the resources to fund overseas fieldwork, my counterparts at the University of Zambia (who are surely better placed to investigate the causes of rural-urban differences in their compatriots’ gender beliefs) juggle short-term consultancies, with little opportunity to pursue their own research agendas.

The above-mentioned occurrences were also rather minor. It is almost self-indulgent to mention them. I escaped to the cooking hut entirely unscathed – quite unlike the young woman seen the previous day, battered by a man she had spurned. That – I learned – was an all too common event in the remote rural village, with no police station.

Additionally, they were extremely isolated instances. They were vastly outnumbered by displays of great kindness and generosity. Concerned about my welfare, fellow bus travellers came to rescue me from the Congolese officials. One man offered £5 (not a minor sum) in exchange for my release. On another occasion, while I stood idly at a quiet junction in the middle of nowhere (fruitlessly fretting over whether I would reach my destination by nightfall) a police officer was speaking to drivers on my behalf.After an hour and a half of waiting, a 4×4 is waved to a halt. My heart leaps. Two commercial farmers (a married couple, with a driver) agree to take me on the six-hour journey. They beckon me over. I bounce over in euphoria. I bought them copious provisions for the journey and found some cardboard boxes to shield my suitcase from the chicken mess in the back. They seemed highly amused to find an overjoyed white lady in the middle of nowhere, fluent in Bemba and asked all sorts of questions. Comfortable vehicle, superb driver, plenty of space, friendly people, but not overly so – unbelievable good fortune. Whipping out my travel pillow and eye mask, I napped like a child at peace.Countless others would always message me, asking if I had arrived safely after long journeys.

Further, the two young men who grabbed and groped me were exceptions to the rule. Despite the anxiety I experienced when navigating the narrow market corridors, squeezing past a certain group of unemployed young men (often inebriated or high on glue), they always treated me with great respect, wishing me well. Similarly, when I called two male parliamentarians – about the offensive text from their colleague – they were outraged.

The methodology sections of my papers won’t include details about sexual assault, hazardous journeys or minor eye infections. But I do think we – as researchers – should talk about them.

Not without checking our privilege, however.

[Oh, and if you’re interested in my research findings then click here. In brief, urban heterogeneity and density seems to increase the likelihood of exposure to a critical mass of women performing socially valued (masculine) roles. This undermines assumptions that women are less competent and less deserving of status. Furthermore, greater proximity to clinics and police in urban areas disrupts biology: enabling women to control their fertility and secure external intervention against gender-based violence. This explains why we see greater support for gender equality in urban (rather than rural) areas. But of course I’ll need another couple of – hopefully less eventful – fieldwork trips to fully test this hypothesis].

LSE’s Alice Evans is a Fellow in LSE’s Department of Geography.

You do paint a very gloomy picture of your ” fieldwork”, despite the attempt at balancing it off in relating some acts of “kindness”. It reads more to me as a narration of the experiences of unpleasantness, than a checking of privilege. Nothing here, at least for me, departs from the cliches of doing fieldwork in ” Africa”. Then again, it is the LSE, one only hopes for more complexity. Well, it is Africa after all, isn’t it?