Katarzyna Kubin says on Bahru Zewde’s recently re-published book: The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement c. 1960-1974 gives a detailed account of the Ethiopian student movement, emphasising its role in the 1974 revolution.

The esteemed Ethiopian historian, Bahru Zewde’s most recent volume, The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement c. 1960-1974 (Addis Ababa University Press, 2014), has been newly released in paperback (James Currey, 2017). The book was much anticipated by scholars interested in this crucial period of Ethiopian history, which led up to the ousting of Emperor Haile Selassie I. The book gives a detailed account of the Ethiopian student movement with the aim of both clarifying its evolution and emphasising its role in the 1974 revolution. It neatly follows Zewde’s previous Pioneers of Change in Ethiopia (2002), which focuses on the first half of the 20th century and spotlights the work and lives of public intellectuals committed to reforming the Ethiopian monarchy.

The Quest for Socialist Utopia is based on archival material, including student publications, official documents (from the university, police, government), and newspapers, as well as accounts from individuals who were involved in the movement during the 15 year period covered by the book. The study charts the development of the student movement from its beginnings when students’ activities were entrenched in Selassie’s newly established higher education institutions, through a period of growth and radicalisation in the 1960s when student groups, events and publications became platforms for increasingly overt opposition to the stifling imperial order. Zewde’s study also traces the progressive development of differences around discourse, focus and tactics within the movement as it neared its climax as a significant political force in the 1974 revolution, which eventually contributed to its dissolution.

The analysis is firmly grounded in the social and political dynamics inside Ethiopia, but also addresses the significant role of the student diaspora outside the country and systematically takes into account the broader geopolitical situation of the Cold War. Throughout the analysis, Zewde is self-conscious in his use of labels such as local and “Western”; conservative and modern; domestic and foreign. The effort to destabilise binaries that often structure comparable historical studies contributes to Zewde’s convincing depiction of the radicalisation of the movement “as a process rather than as a sudden development” (p. 135). Zewde positions his study in contrast to other scholars, notably Messay Kebede, whose Radicalism and Cultural Dislocation in Ethiopia, 1960-1974 (2008) presents Marxism-Leninism as an external influence that was key to radicalising the movement, a view that Zewde considers misrepresents the movement as ideologically driven rather than grounded in local social realities.

The thematic organisation of the book supports the nuanced perspective that Zewde endeavours to give on the subject. The first chapter “Youth in Revolt” places the history of the Ethiopian student movement in a global context by highlighting temporal and thematic similarities in student activism around the world, a point further emphasised in both the introduction and the conclusion to the book. Chapter 2 “The Political and Cultural Context” sets out how the central figure of Haile Selassie I, though initially consolidating support, ultimately sets the framework for opposition in its various political and cultural expressions. Chapter 3 “In the Beginning” outlines the formation of an institutional framework for the student movement (e.g. unions, publications) with attention to the place and role of Ethiopian students active abroad. Chapter 4 “The Process of Radicalization,” arguably the heart of the book, considers a range of factors, “both internal and external” to Ethiopia, that helped root the movement in local social issues (e.g. civic rights, freedom of expression, poverty) and thus to crystalise its anti-feudal, anti-American and anti-imperialist positions. Zewde considers, among others, the failed coup in 1960, the “Land to the Tiller” demonstrations (1964-65), the presence of an interaction with students from other regions of Africa within the university, the increasingly repressive responses from the university administration and the government to student activities. Chapter 5 “Prelude to Revolution” discusses the spread of opposition activism from the students to the general population. The final two chapters of the book – Chapter 6 “Championing the Cause of the Marginalized” and Chapter 7 “Fusion and Fission” – highlight the diversity within the student movement. The former focuses on the precarious situation of women in the movement; the latter on differing strategies for building strength and momentum, with particular attention to the debate over focusing on class or ethnic identity in mobilisation efforts.

Although meticulously and steadfastly evidence-based, Zewde’s depiction of the student movement sounds romanticised at times. In his review of the book, Kebede notes Zewde’s tendency to highlight “youth altruism” in a way that can obscure the “structural causes” of the movement’s radicalisation (e.g. unemployment, government repression, lack of social mobility).[1] Moreover, the broad-stroke references to student activism around the world at times come off as fragmented and superficial, and also go some way to undoing the efforts to contextualise this period of Ethiopian history in the dynamics and events of the Cold War specifically. The emphasis on inserting the Ethiopian student movement into a general global context also draws attention away from this period as especially significant for radicalization across soon-to-be-postcolonial Africa (and Asia) in particular. Even small shifts in emphasis and orientation could have accounted for these issues without undermining Zewde’s important efforts at nuance as a response to the problems he identifies in other studies of this period in Ethiopian history. The preference for a thematic over a strictly chronological analysis distinguishes this study as it highlights important aspects of the history, such as the place of women in the movement. A more decisively thematic approach could have made other relevant issues similarly prominent (e.g. a Pan-African perspective; the interconnections between Ethiopian students abroad and inside the country).

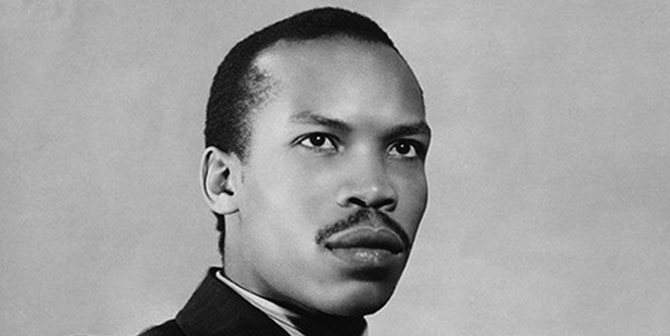

The Quest for Socialist Utopia is an important contribution to scholarship in a range of fields: contemporary Ethiopian and African history, Cold War history, as well as intellectual history, the history of student movements and anti-colonial movements. The densely crafted account can be overwhelming for beginners who may find themselves losing sight of the broader historical arc of events. At the same time, such a rich and nuanced treatment of the topic is possible thanks to the author’s own involvement in the events he documents (e.g. the reproductions of documentary photographs from the author’s personal collection memorably illustrate the narrative). The personalisation of the historical narrative by Bahru Zewde – Emeritus Professor at Addis Ababa University, Fellow of the African Academy of Sciences, and Vice President of the Association of African Historians – makes this exceptional work stand out also for how it bring history to life.

The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement c. 1960-1974 by Bahru Zewde. Published by James Currey, an imprint of Boydell and Brewer Ltd. 2017. (originally published by Addis Ababa University Press, 2014).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Katarzyna Kubin is a PhD candidate at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, based at the Centre for Cultural, Literary and Postcolonial Studies (CCLPS). She is also co-founder and current Executive Board member of the Foundation for Social Diversity, a non-government organisation based in Warsaw, Poland, that deals with issues of migration, equality and social diversity.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog, the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa or the London School of Economics and Political Science.