Doctor Ahmed Vandi describes the panic during Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak in 2014/15, recounting from experience the stigmatisation, confusion and dilemmas that came with working alongside medical colleagues, patients and survivors.

This post is part of Njala Writes, a blog series resulting from a writing workshop hosted at Njala University, Sierra Leone in June 2019, in collaboration with the LSE Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa.

By its nature, the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in Sierra Leone created a lot of panic and fear among people in their communities. The high mortality from the disease brought a lot of social problems.

When my final year student handed me his dissertation in July 2015, back from the field, I didn’t know my life would forever be affected by that exchange. He had spent three months on an internship at the Kambia government hospital in the Northern Province of Sierra Leone. He was infected from a patient he assisted with a doctor in theatre. The doctor became infected and later died in Freetown.

This particular student travelled back to Bo to meet with his department. Two days after receiving his books, one of the relatives made contact to inform me that our student was developing a fever and, over the past few nights, was observed to be weak. The Kambia Hospital administration was immediately contacted, and I was told that he left the hospital without informing the authorities. He was suspected of being in contact with one of the confirmed Ebola cases.

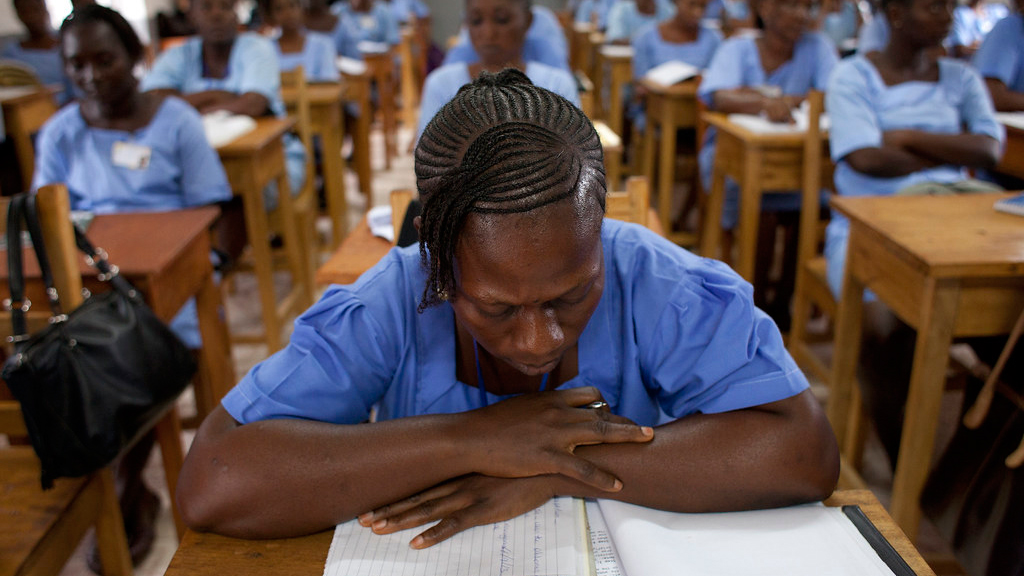

Students and lectures/teachers in the health training institutions were especially vulnerable to the infection. Some students contracted the virus in their learning activities or practices, and later died. Others survived while some people narrowly escaped the infection. Such survivor stories and experiences about the Ebola epidemic must be revealed to elucidate clearly the extent of infections and people seriously affected.

In Bo, this student was staying with relatives in an overcrowded location. He was later contacted by phone for further information about his contact history. He explained to me, ‘Mr Vandi, to be very honest with you, I assisted one of the doctors to do a procedure at the theatre and I have been experiencing some challenges with my health since then’. It became evident he had come in contact with a case of Ebola at Kambia Hospital.

In order to protect the family members he was staying with, I immediately requested he keep away from them, putting in place measures for the ambulance service to take him to the triage at the Bo government hospital. At first he vehemently refused the ambulance transfer, but people’s growing suspicions of his status convinced him to be taken. ‘I will be ready to walk to the triage instead of entering into an ambulance, so you just come and lead me through!’ The following morning, after a discussion with his landlord, I sent everyone including bystanders away from the scene. He walked behind me while we made our way to the hospital with an agreeable distance between us, reaching the triage after a two hour walk.

My own dilemma and confusion about the EVD infection started after closely following up the laboratory investigation into the student at the hospital. Thirty-six hours later, his result was sent back to the holding centre and the results were positive.

My initial contact with the student was now worrying. I contemplated either keeping away from my family members and close friends and/or going to the triage to determine my Ebola status. At this time in Sierra Leone, there was a fear of being stigmatised by being associated with EVD patients or survivors. This view, held by the community, was informed by the number of people with suspected cases taken to the hospital who never returned to their houses, without a solid understanding of how the disease was contracted.

I tried isolating myself for the recommended three week period. I only found myself relaxed after this period.

Two weeks later, I had a call from the Ebola Treatment Centre workers who informed me that the student had been discharged. He sent me a message, grateful for helping save his life. He later brought me his discharge ticket and Survivor Certificate. We ended up having a long conversation in which he vividly explained his experience. I told him how I was seriously affected by the incident myself, but of course without a certificate. There is a sense in which we are both survivors.

Photo: UNMEER/Martine Perret