Ethiopia’s garment industry has seen rapid expansion in recent years, with tens of thousands of women migrants moving to urban areas looking for work and freedom from family structures. Often facing structural barriers in their new homes, these migrants are looking to social networks and self-help groups as alternatives to welfare.

In Ethiopia’s efforts to accelerate economic development, has gender equality and the welfare and rights of women migrant workers been compromised? The expansion of garment manufacturing has been an essential component in the country’s strategy to attract foreign investment, but women’s status as migrants who work in this sector makes it difficult for them to attain full citizenship. This status limits their capacity to access services or gain equitable ‘rights to the city’.

Whether women can participate in civil society determines their ability to challenge societal norms and power relations to which they are subjugated. Other challenges such as inflationary urban living costs, limited housing and poor infrastructure, which are in part a result of Ethiopia’s social and economic policies, have compounded the hardships of day-to-day life, despite women earning comparatively higher wages than in rural areas.

My research investigates how these migrant women workers use associations and networks in Hawassa to cope with the challenges of a new urban life, and questions their ability to claim citizenship and full and equal rights in a city with an ever increasing proportion of women. This is especially pressing given the country-specific challenges of transferring rural identification papers to urban areas, and the consequent effects on living and working conditions; in Ethiopia, society is arranged into a formal structure, around a village sized unit known as a Kebele, inside which structure citizens are granted identification papers that enable them to access local welfare services and participate in wider society.

The Hawassa Industrial Park

Hawassa is the capital of the most ethnically diverse region in Ethiopia, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). The city plays an important role in Ethiopia’s recent drive to industrialise though a focus on labour intensive garment manufacturing, which attracts foreign global value chains by offering low energy prices, low worker costs and tax breaks. Over 17,000 young women from predominately rural areas and a variety of ethnicities have, from 2017, migrated to work at the Hawassa Industrial Park (HIP), employing around 120,000 mainly women workers at potential full capacity. They face long shifts, low salaries given living costs between 800 to 2000 BIRR a month (US$27–68) and new challenges in an unfamiliar urban context, which are exacerbated by their status and dislocation from familial networks.

Dislocation from the confines of traditional rural family life to an urban life, free from patriarchal dominance, could be an emancipatory experience for women with new freedoms and choices. A more gender equitable city could be created should women be able to claim full rights as citizens, be empowered and able to participate fully in society.

However, this context presents particular challenges that weigh heavily on new urban residents. The city has a history of tension between the majority Sidamo population and other ethnicities, exemplified by outbreaks of violence around the Sidamo Fichee-Chambalaalla festival in July 2018. During this period many non-Sidamo women felt vulnerable, unwelcome and were unable to access freely the city due to the threat of ethnically motivated attacks.

As is their constitutional right, the Sidamo population have been pressing for a referendum on the formation of an independent Sidamo state. In 2019, as expected, the festival was marked by more violence as the deadline for a federal decision on the referendum drew near. This was in the context of countrywide ethnic tensions were exacerbated by two high profile political assassinations in June 2019, leading to a two-week long internet shut down.

Thanks to the support from academics in Addis Ababa and Hawassa I was able to organise four semi structured focus group discussions and two oral history interviews in Amharic and Sidamo languages, held at the University of Hawassa. To reflect the ethnic make up of the city, half of the 37 women respondents were Sidamo and half a variety of other ethnicities, the majority of whom had moved to the city from surrounding rural areas. Most non-Sidamo workers lived in slums to the north of the city, with Sidamo women generally living in southern peripheral slum areas. The discussions gained detailed insights into the challenges that the women faced in their daily lives.

All respondents faced difficulties in accessing decent housing and most were forced into sharing in groups of four or five people to a room. Conditions were almost always poor with inadequate water and sanitation facilities, limited local infrastructure (transport, health services) and a lack of security or policing. Ethnic tensions have meant that women from ethnic groups other than the Sidamo felt particularly vulnerable and unwelcome in the city.

Housing costs were high and rising due to significant demand and a limited supply compounded by land shortages and rife land speculation. The combination of the women’s locational disadvantage, the lack of transport infrastructure and long shift work meant that most struggled to engage in other activities or form relationships outside work or travel regularly to the city. The research also highlighted difficulties that arose in transferring women’s rural identification papers to the city, which excluded women from the urban Kebele structure, thus limiting their access to services and ability to participate in civil society.

Ethnic and religious associations in the Sidamo area provided valuable practical and emotional support to residents. Intra-household associations were also a common means for women to pool salaries and resources, with loan provision and protection in the event of sickness and an equitable division of household responsibilities.

Some women had begun to enjoy a greater sense of independence in the city, and three women had grasped the opportunity to pursue further education. This in turn expanded their networks and sense of belonging.

To deal with new urban hardships and compensate for the lack of welfare provision, women have had to rely on self-help groups within the household and gain support from neighbourhood ethnic and church networks. While female only households offer benefits over those of traditional families, including the removal of the threat of domestic violence, financial freedom and enhanced mobility, Hawassa has presented new threats and challenges. These challenges have constrained many of these women’s abilities to access welfare and services, navigate the city and fully participate in civil society.

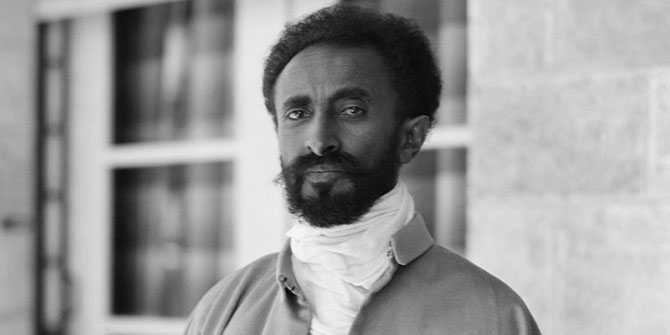

Main photo: Huajian shoe factory in the Eastern Industrial Zone in Ethiopia. Credit: UNIDO (CC BY-ND 2.0).

Its an interesting issue, how i can get

a full version of the study ? Please, use my e mail address.

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to you for this inspiring article. Every word you write touches my heart and soul. I hope you will continue to share your thoughts and experiences.

What a meaningful and humane article. Thank you for sharing with us. Now let’s try to play the game with me.