In recent years, China has overtaken the US to become the world’s largest foreign direct investor into Africa. LSE Senior Visiting Fellow Shirley Yu explains the motivations behind the rise of these investments and the extent of similarities between the African continent and twentieth-century China.

This article is part of the China-Africa Initiative series, exploring the deepening economic interconnectedness of Africa and China.

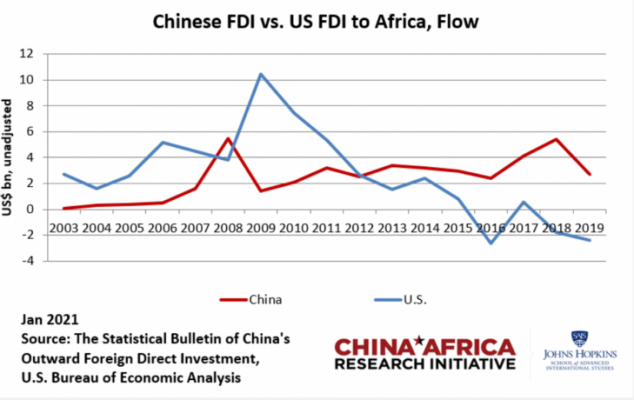

In economic terms, 2013 represented a pivotal shift for Africa, when China overtook the US as the continent’s largest equity investor as measured by foreign direct investment (FDI). After 2017, China continued to replenish the investment capacity into Africa that the US withdrew, motivated by the strategic importance of their compelling economic complementarities and Africa’s potent future as the world’s next engine of economic growth. This pivot may have marked for the continent an irreversible turn.

China, as the largest recipient of global FDI in 2020, and so far in 2021, is fully aware of the power FDI had in transforming its own economy, once the economic gates of the Middle Kingdom opened to the rest of the world in the late twentieth century; today, Africa embodies striking geographical and economic similarities with the China from four decades ago. In 1978, when China began its policy of ‘Reform and Opening-up’, it housed a population of 956 million with a median age of 21.5 years. Africa today is inhabited by 1.3 billion people, with a median age of 19.7 years – a massive, young and low-cost labour force eager to learn and desperate for the pursuit of a better life, now as much as China then.

China has long coastlines on the East and Southern borders, ideal for an export-led economy and, indeed, trade became the first driver of China’s modern rise. Africa has 30,500 km of coastline, cuddled by oceans on both sides. It is endowed with abundant natural resources, rich agriculture with only 25% of the arable land cultivated, and increasingly burgeoning manufacturing industries, which all seek global markets.

FDI inflows contribute significantly to income rises, trade and the invigoration of the industrial economy, but it also plays a crucial role in advancing the soft side of development, such as technologies, labour training and business management knowledge transfer. Africa’s development will surely be better off with FDIs than without.

But given the prominence of Chinese equity investments in Africa, it is important to dispel some myths.

Who are the Chinese equity investors in Africa?

Chinese private companies account for 90% of the total number of Chinese companies investing in Africa, and 70% of the value of Chinese FDI, according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. By the end of 2010, the number of Chinese companies operated in the continent was 1,955, with more than 100 state-owned actors.

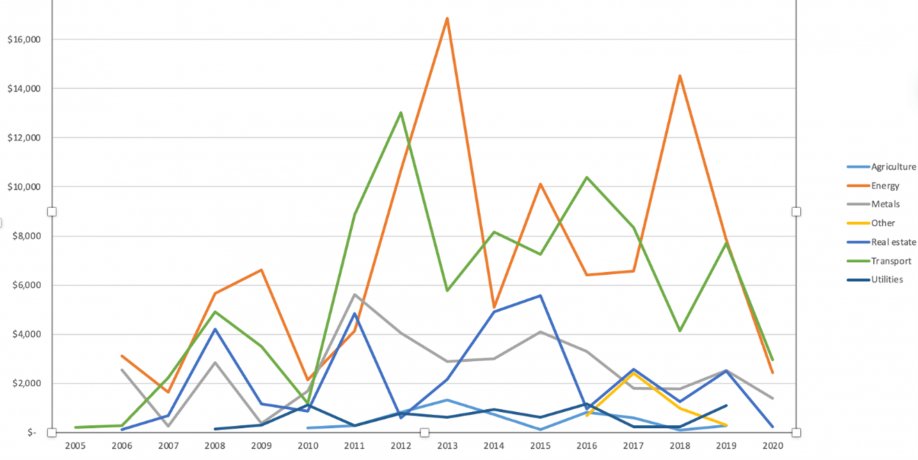

Make no mistake, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are still the largest investors in Africa by value and continue to dominate the energy, transportation and resources sectors due to the strategic nature and long-haul return of these investments. For instance, one third of Africa’s power grid and energy infrastructure has been financed and constructed by state-owned Chinese companies since 2010. China is the most significant foreign contributor through SOEs and state-owned banks to Africa’s energy development.

Yet private Chinese multinationals in Africa are not motivated by the goals of the Chinese state. Rather, they are captivated by Africa’s future, much like Western companies were charmed by China’s 40 years ago. China’s FDI into Africa is more seeking to complement its own development than replicate it elsewhere.

Five reasons why Chinese private FDI is flowing into Africa

Reason 1: China no longer has the labour premium

China is ageing at turbo speed. In 2022, China will become a deeply aged society and, by 2050, the median age is expected to be 51. For comparison, it is expected to be 43 in the US and 47 in the EU. By 2060, one third of Chinese citizens will be older than 65, making China one of the most aged countries in the world.

All this means that China becomes old before China gets rich. When the US, Japan and South Korea hit the 12.6% aged population mark (people aged 60 or above), their average GDP per capita was $24,000. At the same ageing level, China’s GDP per capita was $10,000.

By 2034, Africa’s labour force is forecast to surpass that of China and India combined. By 2050, the African population is expected to be 2.5 billion, while China’s population will decline to below 1 billion. With these figures in mind, Africa’s young labour force is exactly what China’s labour-intensive manufacturers seek today.

Reason 2: China is no longer low-cost

China’s per capita GDP hit $11,000 in 2020, solidly placing it in the upper bound of a high middle-income country and touching the high-income country territory. Consequently, it no longer has the labour cost efficiency essential for middle to low-end global supply chains. By contrast, sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP per capita was $1,596 in 2019.

For this reason, Chinese companies are proactively integrating global productions in demographic regions that resemble China’s scale and capacity, notably in the ASEAN economic union and, increasingly, in Africa. Chinese industrial equipment behemoth SANY Group localised its production in the continent with a 60% African workforce, currently running 12,000 heavy excavators on African soil and including a joint investment with the Kenyan government to build 35,000 housing units in 2019. Considering China’s relatively high labour costs and logistics expenses, it is much more appealing for the company to produce in Africa for Africa.

Reason 3: China has shifted from a large agrarian economy into the world’s largest agricultural importer

Chinese pork inflation hit 112% between 2019-20 and food inflation was persistently in double digits over much of 2020. At the same time, China’s rapid urbanisation has eroded much fertile soil and lured the farming population away from rural areas for city lifestyles, deserting land for salaries. As China’s middle class is expected to balloon from 400 million to 800 million by 2030, China’s structural agricultural insufficiency is not only a potential social destabiliser but a national security threat.

China imports a range of African agricultural products from grains to red wine. As US-China geopolitical tensions intensify, China is increasingly diversifying its agri-imports from the US to other economies. Africa’s agricultural trade with China, and China’s agritech investment in Africa, serves both commercial and strategic purposes.

Reason 4: As China turns itself from the World’s Factory into the world’s consumer market, Africa’s exports to China can only rise by investing in upstream production

Since the 2000s, China’s trade with Africa has multiplied by 20 (breaking $200 billion in 2019) and its FDI into Africa has multiplied by 100 (reached $49.1 billion in 2019). China’s FDI stock in Africa totalled $110 billion in 2019, contributing to over 20% of Africa’s economic growth. Chinese FDIs have scaled up African supply to satisfy the rising middle-class demand.

Reason 5: Africa is a fast-growing consumer market

Africa has a population of 350 million middle class, which is comparable to China’s 400 million. Similarly, Africa’s share of people living in urban areas was 40.7% in 2019, while the same rate of urbanisation in China is about 55%.

A rising middle class in Africa shares similar desires to consumers back home, with demand rising for smart city development, energy, consumption, education, entertainment, finance and health. Savvy Chinese private companies are venturing into all these areas, exporting China’s business models, IP and technology platforms fit for emerging markets.

The limit to China-Africa similarities

It is, however, a mistake to treat Africa as a single frictionless economic body similar to China. Africa is not a single market, but we should strive for its culmination.

Africa’s economy is inherently stymied by intra-continental barriers to trade and blockages to the flow of business, information and logistics from one country to another. Economies of scale, legal system standardisation and a single market are appealing for FDIs, which the commencement of the Africa Continent Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in 2021 brings closer to a reality. The degree to which Africa can truly replicate some of China’s development successes, and reap the benefits of growing FDI, may depend on how the free trade area progresses.

Find out more about the China-Africa Initiative based at the LSE Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa.

We will review China’s role in Africa’s special economic zones and free trade development in the next post in the series. Read the first post here: Three reasons why Africa’s digital future is deeply intertwined with China.

Photo: South Africa – China bilateral meeting, 19 Feb 2017. Crediy: DIRCO. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

“Africa’s economy is inherently stymied by intra-continental barriers to trade and blockages to the flow of business, information and logistics from one country to another. ”

A consequence of the European ‘scramble’ since Roman times and Caesar’s premeditated ‘divide et impera’ strategies, continued through the corporate savagery to extract resources, not least human ‘resources’ as slaves.

Let us hope China continues it’s current enlightened self-interest of balanced inclusivity, and that it does not degenerate as ‘western’ capita£i$m into flat-Earth rapacity under it’s $t€a£th neocolonial apartheid by cultivating client qui$£ing dictators in artificially imposed states.

The “China’s FDI stock in Africa totalled $110 billion in 2019” seem a little too much. The SAIS-CARI advace a figure of 44 in China stock of FDI in 2019. Could you please source or decompose the 110 billion figure?

Thanks for the complex analysis. I learnt the trends and dynamics of FDI, however, recommendations are needed for the African nations FDI negotiation and agreements

I learnt the trends and dynamics of FDI