Efficient and effective international governance is to a large extent dependent on the quality of recruitment of human resources into international organisations. A recent study of recruitment and staffing at the African Union Commission mapped staff composition, showing that the organisation is heavily dependent on short-term contracted and lower-ranked personnel. The study demonstrates that informal international practices are deeply embedded in the Commission’s recruitment processes, which has huge implications for staffing, recruitment and performance in international organisations more broadly.

Over the past decade or so, international bureaucracies and international civil servants have come to the forefront of academic interest in international relations and public administration. Studied under the umbrella term of ‘International Public Administration’ (IPA), this scholarship has provided ample evidence to show that international civil servants – even more than public administrators in the national public service – matter. These studies show, for instance, that international administrators have significant impacts on decision- and policy-making in their respective organisations.

A major weakness of this exciting but nascent field is that many of the studies are confined to organisations housed in countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, in particular those with relatively strong executive commissions such as the European Union or international secretariats such as the United Nations organisations, the World Trade Organization and the Bretton Woods system. The blatant neglect of Southern-based international organisations and their bureaucracies, especially those in Africa, is surprising given the centrality of regional economic communities and continental organisations.

This study sought to address this gap in our knowledge by trailblazing into international organisations on the Africa continent. The work focuses on staffing of the African Union Commission (AUC), which was established in 2002 out of the transformation of the Organization of African Unity to the African Union in 2001. In functional terms, the AUC acts as the ‘engine room’ of the pan-African organisation by managing its day-to-day affairs. Its functions highlight the AUC’s central role in contributing to pan-African integration and management of African affairs. Indeed, the AU Commission has developed into a significant actor in both African and global affairs.

The AUC has two-types of staff: elected political leaders and appointed professional international civil servants. The eight elected officials are the Chairperson of the Commission (COC), the Deputy Chairperson of the Commission (DCP) and six Commissioners. Each Commissioner heads one of the six AUC departments. The appointed staff of the AUC are made up of approximately 1,720 (as of May 2020) at the headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and at the representative missions around the world. They are categorised into two groups: the Professional Staff (ranked from P1 to D1) and the General Service Staff (GSS). The General Service Staff people are grouped into GSA and GSB. The GSA people are primarily administrative, clerical, maintenance and paramedical personnel, while the GSB or what the AU Commission calls the Auxiliary Staff are mainly drivers and security personnel.

Based on an online survey of the appointed staff, archival studies and interviews, the study finds that:

- A total of 61% of AUC personnel are on short-term contracts, and 73% of its entire AUC workforce are lower-ranked officials or in the bottom half of the organisational pyramid. Some of these lower-ranked officials are deeply involved in policy/decision-making of the AUC, putting into question the assumption in existing scholarship that decision-makers of international organisations are primarily reliant on top-ranked A-level officials (such as senior management).

- Informality – rather than formal recruitment routines – drives the recruitment of staff. The informal practices shaping AUC recruitment consist of unwritten actions, activities, rules, norms and decision-making structures that have emerged in the African Union system.

One example of unwritten practices in recruitment is the decision by the AUC Chairperson to turn into actual appointing power the usual authority given to heads of administrative bodies to rubber-stamp recommendations of recruitment committees/bodies. As a result, it has become common practice for Chairpersons to flip on its head recommendations of the AUC’s recruitment committee called the Appointment, Promotion and Recruitment Board (APROB) chaired by the Deputy Chairperson of the AUC. For instance, it is not uncommon for the Chairperson to disregard the ranking of the APROB and instead appoint a candidate who is ranked last by APROB in a four-persons ranking system.

Implications for public policy in international organisations

These findings have huge implications for scholarship, public policy and international governance. The finding that the AUC is heavily dependent on short-term contracted staff joins previous studies in drawing attention to the emergence or re-emergence of short-term contracting as the preferred approach to staffing of international organisations; contracted personnel have become an important part of international public governance, as governments aim towards more flexibility in the management of international affairs. The re-appearance of contracting staffing has important implications, including the critical fact that it makes staff in international organisations live in precarious job environments and may compromise international civil servants’ security of tenure.

Short-term contracting may also open the door for member-states to use secondments of government officials to control international bureaucracies and lead to short-lived and erased institutional memories, especially in international organisations that do not have stellar documentation track records. In addition, it may make international public governance less resilient. The International Public Administration and International Organisation literature will do well by studying in a systematic way its impacts, especially that of seconded personnel and consultants, on decision/policy-making processes.

Second, the finding that lower ranked staff of the AU Commission are important in its governance contradicts the assumption in existing scholarship which suggests that decision-makers of international organisations are primarily reliant on top-ranked A-level officials. Scholars interested in international organisation and their administrative staff may lose key insights by focusing mainly on senior ranked officials or neglecting junior staff.

Finally, the discovery that informal international practices are deeply embedded in AUC recruitment processes and influence the overall staff structure is significant. Previous studies have ignored, or rendered peripheral, informal dimensions of recruitment in International Public Administration. The informalisation of staffing is unlikely to be a peculiar AUC phenomenon – but one affecting administrative staffing of international organisations in more general terms. Scholars of these areas should pay close attention to this development in recruitment as previous studies show that organisations that practice merit-based recruitment are significantly less marked by corruption than those that recruit on patronage. Civil servants who are recruited and promoted due to their skills and merits, rather than their social and political connections, tend to embrace values of integrity more than others.

The study gauges the degree of meritocracy in AUC recruitment processes by measuring whether expertise is weighed relatively more than the nationality of recruits and the extent to which the AUC emphasises the technical expertise of candidates compared with other formal qualifications, such as diplomatic background (experiences from other international organisations, embassies, etc.). The mainstreaming of informality in AUC recruitment may impact the independence of the Commission, its sensitivity vis-à-vis external actors, and potentially make it vulnerable to corruption. Such informality, however, can be weighed against the flexibility of hiring new staff.

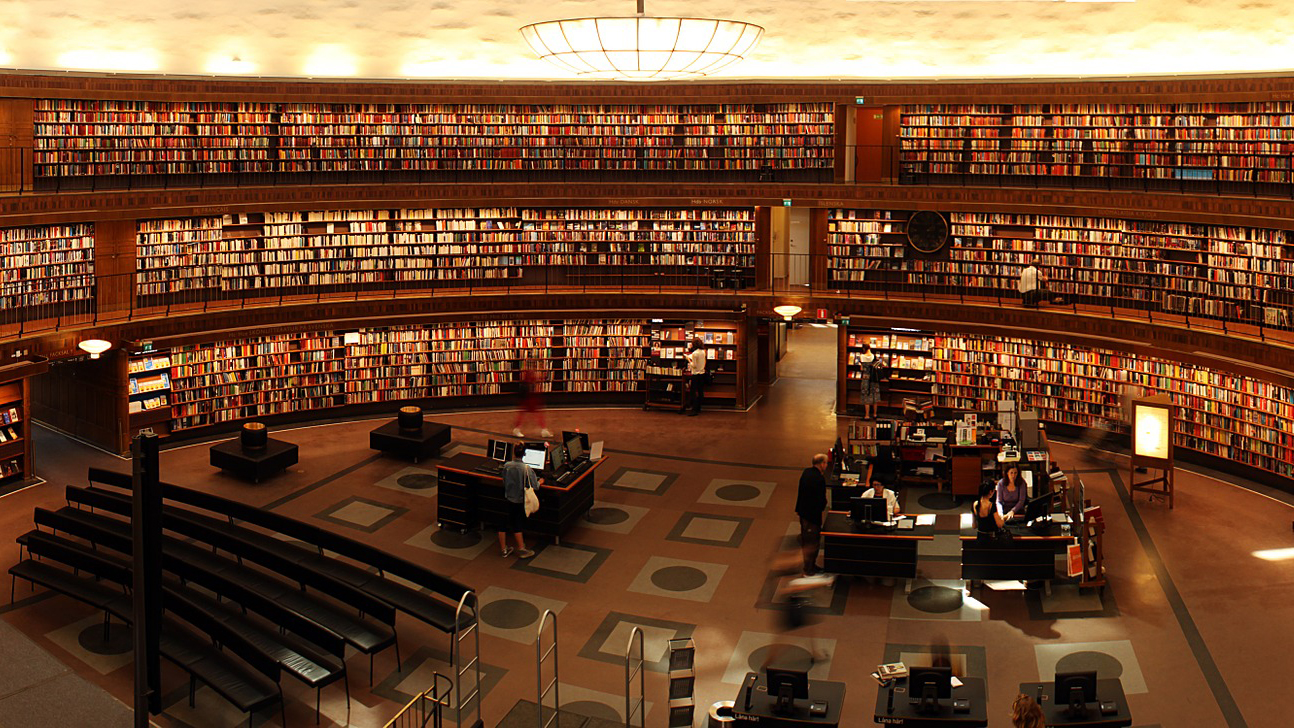

Photo: 17th Ordinary African Union Summit in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea. Credit: Embassy of Equatorial Guinea. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.