Effective political organising is crucial to the success of opposition parties under authoritarian regimes, yet little has been researched about what organising actually looks like on the ground. Fieldwork following the Chadema opposition in Tanzania reveals different practices, in different places, highlighting the importance of innovation among local activists and party leaders.

Many academics agree: to thrive, political oppositions in Africa must organise. Yet their research often reveals little about what such organising involves or how it is done.

Organising is seen as the royal road to opposition victory, especially against authoritarian regimes. When governments choke-off media access, chains of party activists can form alternative channels which carry opposition messages. When security forces crack down on the opposition, organisational structures can absorb the blows.

Nonetheless, understandings of organising remain trapped at the level of metaphors: either construction (party-‘building’) or finance (‘investing’ in party structures). What we know in detail comes from studies of historic trail-blazers like Zimbabwe. These cases are illuminating, but also idiosyncratic. That idiosyncrasy invites the question: does what worked there work elsewhere?

To throw new light on this old subject, I spent much of a year with activists from an opposition party that organised more than almost any other: Chadema in Tanzania. I changed the focus of research. Instead of asking what caused Chadema to organise, I asked: where did it organise, and how (and through whom) did it organise in those places?

I learned that for Chadema, organising was communicative. Both national leaders and local activists described to me organising that was about establishing branches where none had been before, and fortifying branches that already existed. Doing so meant convincing citizens to become party activists who would form and run the branch. This meant that organising involved many of the same communicative and persuasive challenges that election campaigning involved. From the practices that I heard about and observed first-hand, I documented and distilled three modes of party-building. Each enabled Chadema to organise in different places.

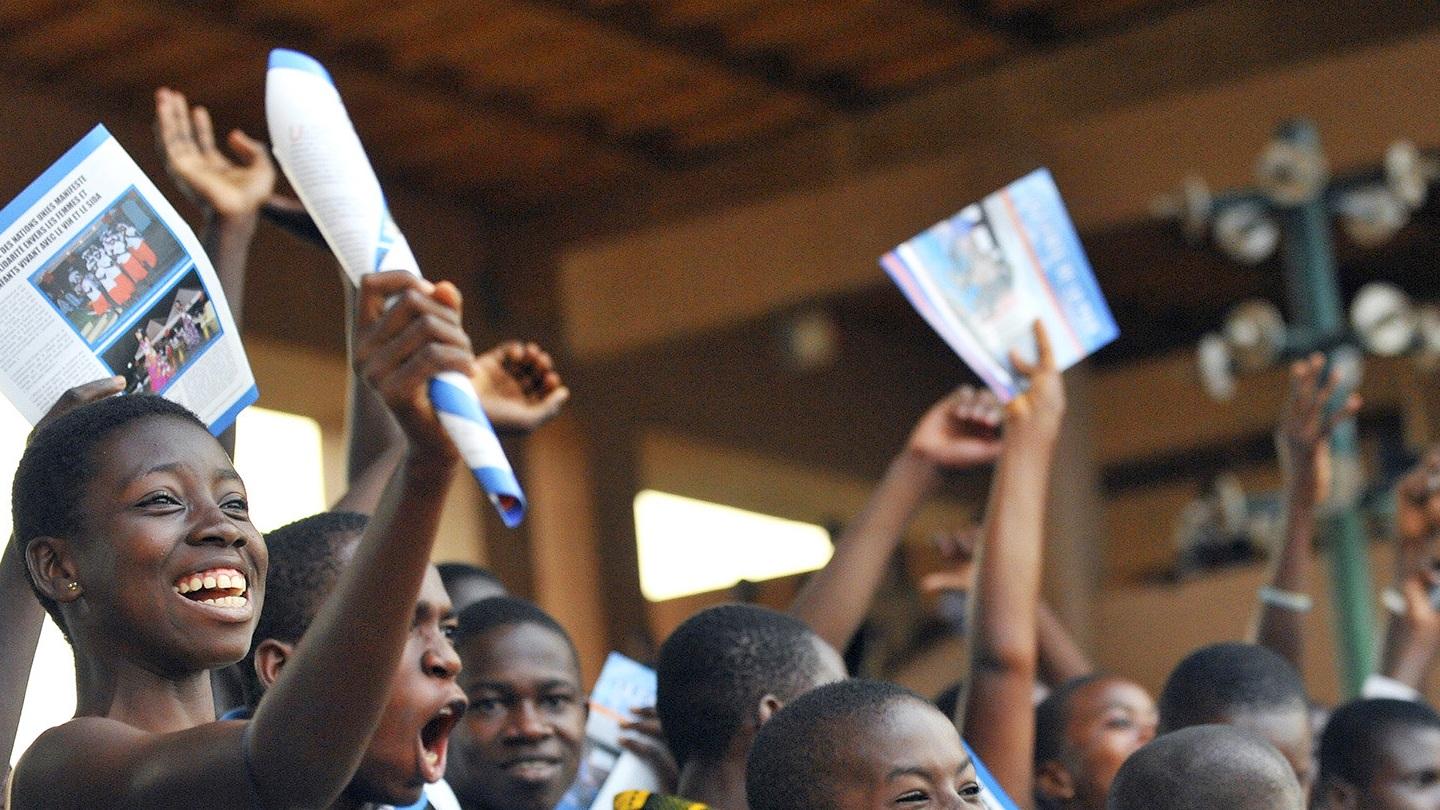

The first is leader tours. Chadema’s leaders held schedules of out-of-campaign-season mass rallies in two ‘operations’: Operation Sangara (2007-9) and the Movement for Change (2011-13). At these meetings, they recruited members. Follow-up teams trained them to establish and grow branches. Chadema’s household name leaders and savvy rally production drew big crowds and won Chadema members, but they also had drawbacks. The national leadership could only be in so many places at once. Only the converted tended to show-up. When the unconverted did show, Chadema had limited means to persuade them in single-shot and, instead, one-way platform speeches were delivered to converted and unconverted alike.

The second is organising by branch members. I saw local meetings, neighbourhood discussions and house-to-house canvasing which were strong where leader tours were weak. Ultimately, leader tours were most effective where citizen opinion was already receptive to Chadema’s message. They played best in cities, towns and regional strongholds, and that is where Chadema’s leaders concentrated. Messages delivered by branch activists could cut through to the unconvinced, but they were immobile. They only operated in or near areas where Chadema was already organised.

Consequently, a geographic pattern emerged. Chadema organised in areas where people were receptive to its messages and where it was already organised, and outwards from both, like wine-drops on cloth. They concentrated these methods least, and made the least progress, in areas where citizens were initially unreceptive to their message.

Chadema’s organising in the Central Zone

There is one area of Tanzania that was emblematic of this sort of hostile environment for Chadema organising, which the party called ‘the Central Zone’. This area, composed of three regions in the middle of Tanzania (Singida, Dodoma, Morogoro), was among the poorest and most rural in Tanzania. At its centre was Dodoma city, the planned political capital and a symbolic heart of the regime’s political strength.

The Operation Sangara and Movement for Change leader-tours never reached the Central Zone. In most of it, Chadema made limited organisational progress by 2015, but with exceptions. In and near the Central Zone, several pockets of Chadema organisational strength emerged. Among them was Singida Magharibi constituency, later Ikungi constituency. It was won in 2010 and again in 2015 by Tundu Lissu, who went on to become a leading face of the opposition to President John Pombe Magufuli. He survived an assassination attempt in 2017 and ran as Chadema’s presidential candidate in 2020. This is his story, as much as anyone’s.

I spent time with Chadema activists in several of these pockets in and around the Central Zone. I concluded that Chadema broke through into these areas because it employed a third mode of organising there: party-building by lone organisers.

In the absence of party leaders and nearby branches, motley groups of activists, often led by those aspiring parliamentary candidates, took on the mantle of Chadema organising. Lissu had clear advice for such lone organisers: ‘how do you beat them? Start early.’ Many did. They invested weeks or months of their time holding out-of-campaign-season rallies, but not the mega-rallies like those held by party leaders, and not confined to cities and district towns. Instead, month after month, they went to village after village, again and again.

At these meetings, often attended by handfuls of local residents, these lone activists and residents conversed. Lissu explained that at such meetings he ‘argued my case in front of the people’. An activist relayed the message of another such Chadema organiser and parliamentary candidate: ‘we need to change the mind-sets of people first and then slowly we shall be instilling the spirit of change as we go along.’ These meetings, in their organisers’ eyes, were sites of persuasion which mixed dialogue and speech-giving. Their modest size made this persuasion more personalised than that at mega-rallies. It was interactive, it was tailored to the individuals to whom it was addressed, and it was carried out iteratively in meeting after meeting. These methods enabled lone activists to operate where party branches and leaders alike could not: in environments hostile to opposition organising, often working beyond the party’s organisational frontier.

Applying the mosaic of organisational tactics

Altogether, behind metaphors of party-‘building and ‘investment’ in party structures lie a wealth of different practices with different strengths and weaknesses. Chadema arranged these practices in a national patchwork, deploying one mode alone in some areas, and deploying them in layers in others. The outcome was a shifting geographic mosaic of Chadema organisational strength.

Like other trail-blazers before it, much about the case of Chadema is idiosyncratic. The practices that crystallised in three modes here may be reflected in other times and places, or they may be rearranged into different forms. It is for others to explore and share the who’s, how’s and where’s of organising elsewhere.

Of course, Chadema’s story did not end when my field research did in 2015. Their organisational gains were stymied, and probably eroded, by the authoritarian turn which gathered momentum in 2015. It is no accident that one of the first planks of the authoritarian programme to be introduced was a ban on out-of-campaign season rallies by all save sitting-MPs. The regime wanted to stop Chadema organising in its tracks. It may well be succeeding. Authoritarian measures were ramped up in 2020 in an ostensible attempt to break the spirit of the opposition for good.

That authoritarian turn so associated with President Magufuli continues to this day under his successor President Samia Suluhu Hassan. The rolling suppression of Chadema’s activities pays testament to this legacy. So does the ongoing trial of Chadema’s Chairman, Freeman Mbowe. Many of the activists who I spoke to in 2015 have gone underground or fled abroad.

Nonetheless, if Chadema’s past teaches us anything, it is its ability, and the ability of the opposition at large, to continually innovate. This year, Chadema’s Operation Haki activist Maria Tsehai pioneered online forum #MariaSpaces and Chadema Digital, which illustrate that creative spirit. Who knows what else will be practiced in the future.

Photo: State Visit of President Samia Suluhu Hassan of United Republic of Tanzania. Credit: Paul Kagame. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.