The way multinational enterprises conduct themselves during periods of crisis, such as an epidemic, is of key importance in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. A health crisis may alter the short-run incentives of some multinationals, encouraging rapacity towards natural resources. Tommaso Sonno and Davide Zufacchi explain that this is what happened in Liberia during the Ebola epidemic in 2014-15.

The number of multinationals’ subsidiaries in Africa has increased by more than 250% from 2007 to 2018 and, more generally, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa has risen by approximately 400% each decade from 1980 to 2015, according to the World Bank. Consistent with the ‘New Wave of Globalisation’ narrative, multinational enterprises (MNEs) have increased their investments in developing countries since the 80s, where returns from capital investments are high due to capital scarcity. This process has never stopped and only grown.

Whether the activity of MNEs fosters or diminishes economic growth in developing countries remains, however, an open question. Moreover, it is important to understand how their incentives interact with health crises in fragile countries. Our recent research investigates this issue by exploring the relationship between the Ebola epidemic, deforestation and palm oil concessions in Liberia.

The Liberian context

After the end of the country’s second civil war (1999-2003), Liberia turned to its natural resource endowments to stimulate the economy. Two major palm oil concessions in 2009 and 2010 granted a total of 440,000 hectares to foreign MNEs. Before converting the land into plantations, however, MNEs must win the consensus of local communities. In particular, once companies have been granted a given concession from the central government, they need the approval of local villages to gain access to their land and start production. This mechanism was thought to reconcile the MNEs’ interests with the need to protect villages and their population.

From 2010 to 2014, Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL), one of the two leading palm oil MNEs, signed agreements for an area of approximately 300km2, with an average of 6.5km2 cleared for usage per month. In the three months between August and October 2014, this number is said to have escalated to approximately 45km2 per month. Why was this happening? According to the NGO Global Witness, state officials had helped the company secure agreements from communities to sign away their land. Many members of the villages were arrested as they refused to give their approval.

Several NGOs including Global Witness became interested in the problem. They visited the communities, monitored MNEs’ operations and assisted locals in filing complaints to the authorities. Interviews with people living in the areas described how local authorities (often village chiefs) took advantage of people’s illiteracy to convince them to sign Memorandums of Understanding. Yet, when the advent of Ebola redirected NGOs’ efforts towards the epidemic, the villages were left without reliable information on the MNEs’ intentions or protection.

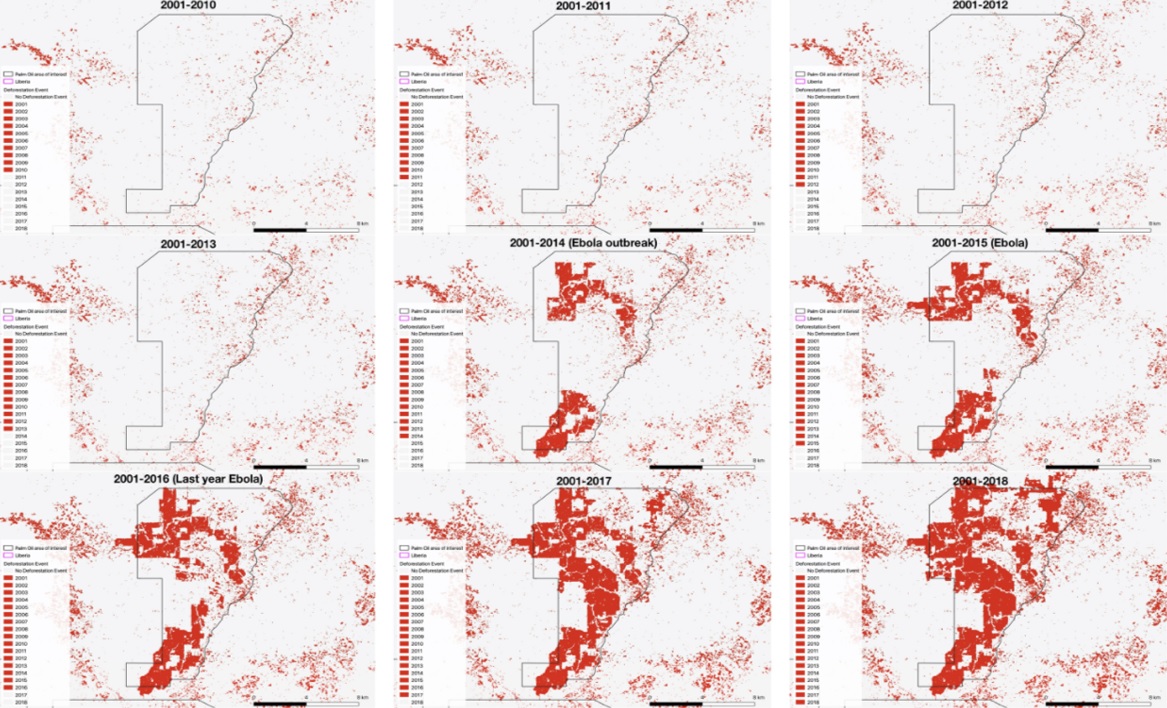

The result of this redirection can be observed in Figure 1, which displays deforestation events for a palm oil area of interest in Liberia. In the first map (top-left), pixels (30 x 30 metres) are red if a deforestation event happened between 2001 and 2010, and one year is added to each following map. As one can see, deforestation events were quite rare within the area of interest up to 2013. In 2014 and 2015, during the Ebola outbreak, there was a sudden leap in deforestation.

Epidemics and rapacity

In order to link the effects of the health crisis with multinationals’ behaviours, we combine the natural experiment provided by the Ebola expansion with a difference-in-discontinuities approach. We compare the percentage of tree coverage in pixels at the concessions’ borders before and after the Ebola outbreak. Our results show a considerable increase in deforestation during the health crisis. Moreover, deforestation has more than doubled (from 3% to 6.5%) in areas where the community is formed by ethnic minorities (defined as groups not represented in central/local government). This evidence reveals that not only MNEs exploited the health crisis, but activities also focussed on the weakest populations, who are not represented in the local or central governments.

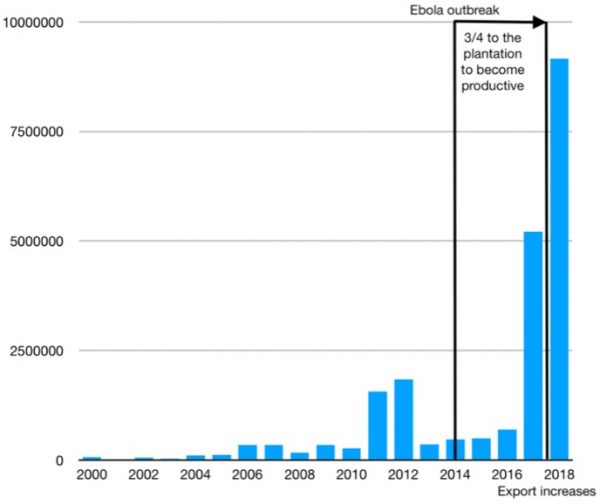

But how did these companies manage to deforest such large areas in so little time? Our analysis provides an answer to this question too: forest fires. The likelihood of a fire event increased by more than 125% in these areas during the health crisis (420% if populated by ethnic minorities). As a result, the percentage of land dedicated to new cultivations increased by 150% during the same period. This rapacity was profitable for palm oil companies, leading to a 1428% increase in the value of Liberian palm oil’s exports (Figure 2). Unfortunately, we cannot say the same for local people or value for the environment.

The power of information

Our work shows how multinational companies may exploit health crises to expand their production, which is usually done at the expense of the local population and environment. Yet, our analysis also provides insights on how to limit these rent-seeking behaviours. The majority of developing countries already have regulations limiting MNEs’ activities, but, because of asymmetric information, their enforcement tends to be weak. Providing the correct information and support to villages may strengthen enforcement, moderating the adverse impact of MNEs’ presence, while preserving the benefits of economic development.

This blog post is based on Epidemics and rapacity of multinational companies, CEP discussion paper No. 1833.

Photo by Pok Rie from Pexels.