The importance of youth mental health is being increasingly recognised as a key determinant of population health outcomes. As the dominant social protection tool across the Africa, could cash transfer programmes act as a tool to improve mental health among this demographic?

This is the first blog of the CHANCES-6 series from the LSE Global Health Initiative.

Mental health conditions are the leading contributor to the global disease burden for young people, with the onset of an individual’s first mental disorder occurring before the age of 25 for more than half (62.5%) of the population. The knock-on effects of not addressing mental health challenges at a young age can lead to problems later in life, including poor health and socio-economic outcomes, such as a lower likelihood of completing education and finding employment.

The challenges in addressing mental illness in Africa

African governments often focus resources on combatting communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. These are seen as more urgent priorities that directly relate to one’s physical health, rather than mental illnesses that are often perceived to be a “white man’s disease” or a problem for high-income countries. This is despite evidence showing that every $1 invested in school-based interventions that address anxiety, depression and suicide returns over $65 in low and middle-income countries over an 80-year period.

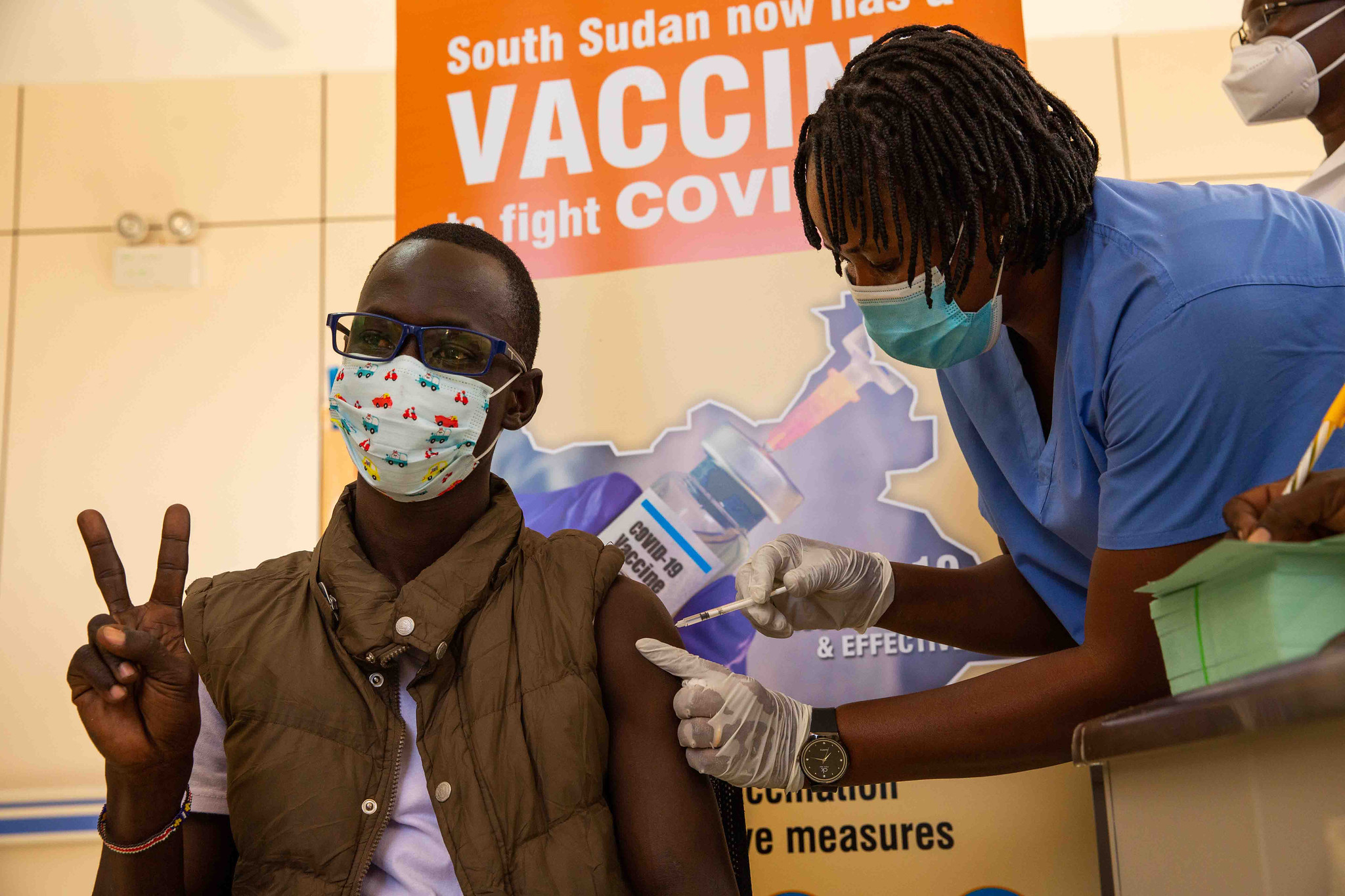

Most African governments allocate less than 1% of their health budgets towards improving mental health, and there is often no budget specifically allocated to mental health for children and adolescents. This has resulted in the global average of nine mental health professionals per 100,000 people – ten times higher than the African average, resulting in treatment gaps for mental health disorders thought to be as high as 90%. The COVID-19 pandemic has only added pressure to health and social care systems already working at capacity, with the increase in youth mental health problems viewed as another pandemic in the making.

There can be little bandwidth among those who are poor to pay attention to symptoms of poor mental health in oneself or others, despite a greater prevalence of mental health conditions in households living in poverty. Mental disorders, at times, are the product of poor social and economic environments, where there are higher levels of violence and crime. Many African languages do not have a word for depression, which can make it difficult for individuals to articulate feelings related to their mental well-being.

Stigma and discrimination with respect to mental health and poverty are still widespread across the globe, and this continues to be a difficult obstacle to overcome in Africa, where mental illness is often attributed to “demon spirits”. A large-scale study of popular attitudes towards people with mental illness in Nigeria found stigma to be widespread, with most people indicating that they would not tolerate basic social interactions with someone with a mental illness. Shame and stigma experienced by those in poverty can further lead to social exclusion and a lack of agency, causing a vicious downward spiral of worsening mental health and entrenched poverty.

With a vast array of barriers impeding the tackling of mental health challenges on the continent, universal social interventions have been posited as a means to prevent the onset of mental illness.

The Chances-6 research programme and youth mental health

CHANCES-6, led by the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre at LSE, is a large research programme covering six low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Latin America. It seeks to explore the relationships between poverty, mental health and future life chances of economically deprived young people.

Cash transfers, both conditional and unconditional, are a well-evidenced and effective social protection tool that provide recipients the means to improve their livelihoods. To date, most of the benefits of these programmes have been traced to reducing food insecurity and restoring dignity to families and communities struggling to break free of the poverty cycle. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted on cash transfer programmes, which included studies from Uganda, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi and South Africa, suggested that cash transfers are associated with small positive effects on mental health in the majority (85%) of studies. The meta-analysis found no effect on depressive symptoms among children and young people.

Research focused on receipt of South Africa’s child support grant, the largest social protection programme in Africa, found no improvements in the psychological well-being of adolescents and young adults. The grant, which provides unconditional cash transfers to children living in households below a poverty threshold, also did not appear to improve education or employment outcomes, indicating limited efficacy in addressing the social determinants of young people’s mental health.

Where might the key levers and opportunities be?

Lost human capital from mental health conditions is estimated to cost over $17bn in sub-Saharan Africa every year. However, a number of place-based approaches tailored to local contexts have been effective in tackling the onset of mental illness across the continent.

In Kenya, the Shamiri Institute has developed a youth-led and oriented grassroots model to deliver mental health interventions. Randomised controlled trials have shown such a model to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety. The Friendship Bench approach in Zimbabwe trains health workers to recognise mental illness using a locally validated assessment tool and offer evidence-based problem-solving therapy in primary care settings. Given the increased community ownership of cash transfer programmes across the continent, localised models could combine community-led mental health interventions.

There has been an explosion of growth in digital connectivity across the globe. As of 2020, 28% of the sub-Saharan African population was connected to the mobile internet, more than double the rate in 2014, with young people making up a significant proportion. Improved coverage could provide another avenue to facilitate delivery of cash transfer programmes in a way that allows them to be combined with digital mental health interventions. Indeed, global investment in mobile mental health interventions is expected to hit $500m in 2022. Last year, Panda launched a mobile application for mental health support in South Africa which gives users access to online resources to help them manage their mental health. Their provision also includes one-to-one support with a registered professional. However, no formal evaluation of this exists to date.

Facilitators of cash transfer programmes would be well placed to leverage innovation in this space to impact mental health positively as a universal social protection measure. Going forward, place-based innovation alongside increasing access to digital connectivity could provide meaningful levers to design and implement effective mental health interventions, using the cash transfer programme model.

This post was first published on the Global Health at LSE blog.

Photo by Ketut Subiyanto.