Despite laws to ban its spread, disinformation is a huge problem in Kenya and threatens to destabilise the country’s democracy, writes Lilian Olivia.

Understanding the difference between disinformation and misinformation can be quite daunting. The crux of the matter is that disinformation refers to the intentional spread of false information while misinformation relates to circulating misleading, false or inaccurate information without any intention to deceive. Under Sections 22 and 23 of Kenya’s Computer Misuse and Cyber Crimes Act, the publication of false information deliberately is a crime punishable under the law. Yet that has failed to stop its spread. The 2022 General Election was, unfortunately, swarming with disinformation. Scepticism, suspicion and fear engulfed opposing sides of the political divide driving them to desperate measures.

Digital platforms are avenues for freedom of expression, public participation and democratic governance debates. However, in the wrong hands, these platforms can amplify disinformation and misinformation. This begs the question: Should freedom of expression be considered a double-edged sword? Tensions are high in any general election and weak content moderation can transform social media platforms into hotbeds of hate speech and disinformation. In the 2017 General Elections, disinformation was common on Facebook through Cambridge Analytica and Harris Media content. In 2022, the number of internet users has grown to 23.35 million due to increased exposure to smart phones and social media and the amount of disinformation was greater than ever before.

During the campaign period between May and July 2022, fake polls, fake news and videos, were disseminated on TikTok and Twitter. Algorithms were abused to amplify the disinformation. ‘Deep fakes’ were the norm for targeting the less informed citizens. A report by Mozilla explains how TikTok moved from being just a Dancing App to a Political Mercenary App during the campaign. Unfortunately, TikTok has weak content moderation policies, and this paved way for gruesome inciteful videos depicting hate speech and propaganda. For instance, a video containing a manipulated image of one of the political candidates as its thumbnail was posted on TikTok. The political candidate had a shirt that was covered in blood, and he held a knife to his own neck with a caption alleging that he was a murderer. This video garnered over 505,000 views on the platform.

Prior to voting day on 9 August 2022, there were false claims of wild animals on the loose in certain regions. Additionally, other false claims included information about candidates having already won the election and claims of military deployment in the capital Nairobi, among other areas. People also shared untrue information that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) had mistakenly added votes to the tally of one of the presidential candidates. Surprisingly, the IEBC provided an open and accessible public portal from which anyone could download results from all polling stations in Kenya. Little did the commission know that it was opening the floodgates of disinformation. The chairman of the commission, Wafula Chebukati, averred that there were numerous attempts to download Form 34C which is used to announce the winner of the presidential election. The East African Data Handlers conducted a separate forensic analysis on the IEBC’s six data transmission servers. The report showed that several unauthorized individuals gained access to the system and tried to manipulate the results. This illustrates the extent in which people were willing to engage in disinformation.

Different media stations aired different results due to their slow pace in tallying the provisional presidential results. Voters decided to watch news from their favourite media outlets that projected their preferred candidate as leading. Bloggers and Influencers for hire were deployed to sell narratives that suit their political side as IEBC was still tallying the results. Verification and tallying of votes took longer than expected, and with each passing day, social media platforms were swamped with disinformation about the results. Mistrust in the election process was common due to manipulated photos and videos. In one such video shared by Azimio la Umoja-One Kenya Coalition leader Raila Odinga’s camp, subtitles are manipulated to depict Kenya Kwanza Coalition leader William Ruto speaking in his local dialect threatening people who were not from Kalenjin tribes in the North Rift region. William Ruto was, however, saying the exact opposite in the original video. He was reassuring the other communities that they are safe living in the region and should go about their business.

According to a survey by Reuters Institute, at least 75% of Kenyan news consumers cannot distinguish between real and fake news online. To curb the spread of disinformation, Twitter introduced a feature to fact check any tweets that involved tabulation of results. However, there were inconsistencies in flagging tweets as not all tweets with disinformation were highlighted. Innovative ways of limiting the spread of disinformation were developed by various civil society organisations, media stations and social media influencers. For example, social media influencers used satirical comedy to disarm viewers through humour, prompt them to consider different points of view and strengthen their critical thinking skills when it comes to the news and information they consume. Civil society organisations opined that pulling down videos was not enough. They advocated for more pay for content moderators in Kenya to give them greater incentive to filter the mammoth amount of information shared during the election period.

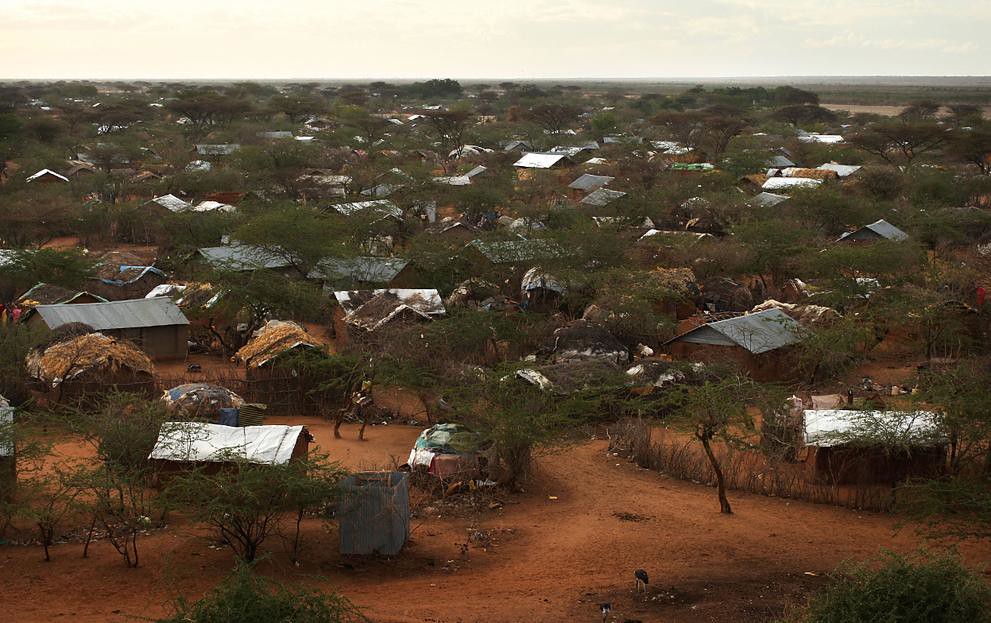

Disinformation could have sent Kenya back to the old path of post-election violence witnessed in 2007-2008. Whenever political campaigns take over, detecting fake from real proves futile for the citizens. False information is a big deal in Kenya because it has previously led to bloodshed and displacement of people. In 2017, through several dark videos and websites, Harris Media attempted to paint Raila Odinga as a monster who would destroy Kenya if he became president. Many of those videos received millions of views on YouTube and Facebook because the platforms were paid to distribute them. Some of that content is still online in 2022. Harris Media injected a new campaign tactic into Kenya’s electoral landscape — one that its political scene has had trouble shaking off ever since.

With the antagonistic nature of the election period marred with disinformation and misinformation, it was commendable that Kenyan citizens were able to rise above the fray and there was not an escalation to violence. Curbing disinformation is complicated and requires all hands-on deck approach. A multi-sectoral approach that involves having fact-checkers, content moderators, civil society organisations, governments, media stations and the citizens all brought on board.

Photo credit: Rawpixel Ltd used under CC BY 2.0