After being supressed by colonial powers, Indigenous Knowledge is making a comeback. It is being promoted by development organisations and Western governments alike, particularly in the field of environmental stewardship. But to understanding its rebirth it is vital to understand its history, writes Ambe Njoh.

Indigenous knowledge, or IK as it is now fondly called, is making a comeback. IK has become a favourite buzzword in international development circles. Leading aid donors are vying for position in a race to incorporate IK in their development projects and programmes.

The World Bank now has an Indigenous Knowledge Program. Not to be outdone, the United States’ White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the White House Council on Environmental Quality have just jointly issued government-wide guidance on IK. It implores Federal agencies working in non-Western settings to recognise and include IK in their research, policy, and decision-making agendas. This marks a remarkable revival for IK in international development thinking.

With IK’s revival has come calls for its incorporation in formal education programmes. However, success in this regard is unlikely without a good understanding of how IK lost its allure in the first place. In Africa, it was one of the major casualties of European colonialism. In their bid to assimilate and acculturate Africans, European colonial authorities instructed them to abandon their cultural and traditional practices: “the Europeanisation of Africa” as Chinua Achebe memorably wrote in Things Fall Apart.

The irony is that Westerners are now instructing Africans to re-embrace the same ways of life and know-how they once disparaged, vilified, and condemned. Such a proposition is bound to encounter challenges, especially in a country such as Cameroon which came under the colonial orbit of multiple European powers. In the face of global climate change, at the forefront of these challenges is how to incorporate IK in environmental education (EE).

Indigenous knowledge and formal education in Cameroon

Cameroon was colonised by Germany from 1884 until the end of World War I in 1918. Thereafter, the territory was divided into two unequal parts of 4/5th and 1/5th and placed under the respective colonial control of France and Britain.

To the extent that indigenous languages can be viewed as a vehicle for transmitting IK, one can argue that some colonial powers were paradoxically more tolerant of IK than others. This depended mainly, although not exclusively, on how they prioritised the need to assimilate Africans. Von Puttkammer, the pioneer German Governor General of colonial Cameroon decreed German as the sole language of instruction throughout the territory in 1897.

The years following Germany’s abrupt exit as a colonial power from Cameroon witnessed ebbs and flows in efforts to incorporate IK in formal education. French colonial authorities shared the view of their German predecessors by prioritising the need to assimilate Africans. This dovetailed neatly into their mission to civilise ‘cultural others’ (la mission civilisatrice). They adopted the German colonial education policy and mandated French as the sole language of instruction in schools.

In British colonial Cameroon, the story was different. Education was conducted on a dual-track system—one rural and the other urban. Native languages were permitted in rural areas (although not in science courses). This continued until the end of the colonial era in Cameroon in 1960/61. Upon gaining independence, the indigenous leadership, like their colonial predecessors, forbade the use of indigenous language as a tool of instruction throughout the country. French was mandated as the exclusive language of instruction in Francophone Cameroon, while English was assigned the same designation in Anglophone Cameroon.

Indigenous knowledge and environmentalism in Cameroon

There is no shortage of indigenous knowledge in Africa. It resides in many sources within any given country including its historical, economic, social, political, ecological, cultural, and technological contexts. Any meaningful effort to incorporate IK in environmental education must utilise these sources.

Traditionally, Africans used oral history to pass knowledge about nature from one generation to the next. Through frequent storytelling, they taught children about their community, its mores, beliefs, and behaviours. They did this during late-evening hours under the moonlight or around fireplaces. The storytellers were usually family elders, who became griots: experts profoundly knowledgeable on African tradition, culture and history.

There were folktales and myths that held that the Earth, including bodies of water, hills and mountains were the home of ancestral spirits. There were also folktales that told of ancestral spirits causing agricultural and human fertility as well as protecting the living from illnesses and other dangers. If nothing else, this gave people reason to be good environmental stewards. Within this frame of thinking, doing otherwise would provoke the wrath of ancestral spirits.

Many African folktales conveyed lessons on environmental stewardship. A common folktale in Anglophone West Africa tells of Mammy Water, the water goddess causing anyone who defecates or dumps in a river or other body of water to drown. Such folktales were meant to discourage people from excreting or dumping in rivers, streams and lakes. Folktales about locusts, droughts, floods, and other devastating natural disasters are also commonplace. Some of these are tales about how communities managed to survive these disasters and became more resilient.

A well-known folktale about disaster survival and resilience is culled from ancient Egypt and mentioned in the Bible (see Genesis 41: 25-36). The tale tells of how Egyptians of the Bronze Age managed to avoid starvation during seven years of droughts thanks to the foresight of their king, who had arranged to save much food during seasons of bountiful harvests. Knowledge of these facts is not only of historical importance. It can constitute valuable input for contemporary disaster mitigation and relief initiatives.

In the name of modernisation and the pursuit of economic growth, the colonial and post-colonial governments in Cameroon have aggressively promoted cash crop farming and commensurate mono-cropping techniques. In doing so, they effectively discourage mixed-crop farming that is indigenous to the country. African IK holds that planting different types of crops, for instance, maize and beans, on the same plot of land increases soil fertility and combats weeds. This tends to increase crop yield. IK also contains information on how to produce insecticides from plant derivatives.

A meticulous comparison of so-called modern farming methods and traditional alternatives provides an opportunity to showcase the advantages of IK over Western knowledge. To be sure, mono-cropping may guarantee higher yields over shorter durations. However, in contrast to mixed-crop farming, it causes the rapid depletion of soil nutrients, soil weakness, and overall soil damage especially because it requires the use of fertilisers.

Incorporating IK into environmental education may involve as little as drawing students’ attention to environmental activities around them. It may require no more than showing students of environmentalism how African norms, folktales, and beliefs relate to what they are taught in class.

Alternatively, it may be more encompassing, including IK as part of the environmental education curriculum and mandating specific activities to be covered. In this case, it can be prescriptive in specifying exactly what activity has to be done. The activity may include taking students on field trips to peasant farming villages. It may also entail inviting local farmers to come and talk about their activities to students in formal environmental studies classes.

However it is done, it is clear that IK will once again play an important role in environmental education.

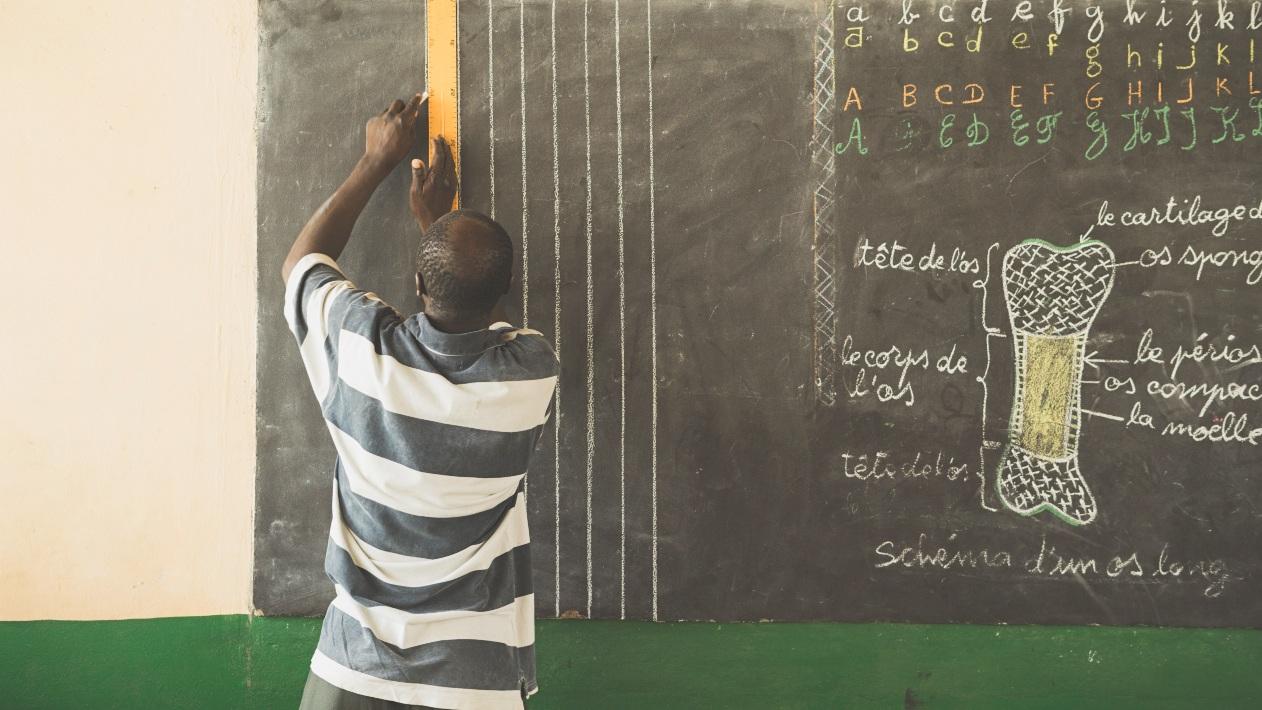

Photo credit: Global Partnership for Education used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

As usual, excellent article prof. I didn’t expect anything less. I thoroughly enjoyed how you shed light on the way our oral myths ensured sustainable environmental practices. Worthy of note is the fact that mono-cropping is focused on cash crops whose price is determined by the buyers to our detriment.

Prof, you quote Achebe’s “Europeanisation of Africa” as a significant catalyst to the demise of IK. I agree with you, given that you develop your argument along the lines of the French colonial policy of assimilation in francophone Africa (voir Paris et mourir) and the Belgian (actually Leopold II) policy of paternalism. However, how did the British colonial policy of indirect rule contribute to the demise of IK? In lusophone Africa, coercive labor, tax exactions, racial discrimination, authoritarian politics, and economic exploitation were the fundamental pillars of Portuguese colonialism in Africa. How would these have eroded IK?

It would be interesting to read from you on cultural appropriation in the future. As usual, thanks immensely for sharing from your fountain of knowledge.

Beautifully crafted, succinct and mind-blowing. Thanks for this beautiful write-up.

Prof. This is thought provoking and I hope it gets the necessary attention from our policy makers.

Thanks, Prof Ambe, for this powerful intellectual and cultural contribution in highlighting and advancing the reemergence of critical indigenous, Afrocentric or what I like to call non-traditional knowledge and development once interrupted by a ruthless colonial experience in Africa. Even with its shortcomings, Africa is bouncing back. You are doing your part in combating the steady drumbeat of negative stereotypes of the continent. Despite the developmental African faux pas by the corrupt and incompetent political class which is a carryover from the colonial era, we are experiencing a reemerging Africa. I am excited and looking forward to the enlightenment from you blog. It was so fitting to hear the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently say, Africa is ‘a source of hope’ for the world, highlighting some of her recent achievements despite the deeply unfair global systems.

Brilliant views. A return to the old is now encouraged after decades of making others feel like idiots.