When the Italian Fascists invaded Ethiopia in the 1930s, they attempted to undermine Ethiopian nationhood by portraying Ethiopia as a colonial state. This rhetoric damages Ethiopian unity and has had violent consequences right up to the present day, writes Birhanu Bitew.

Ethiopia is famous for defeating colonial powers on the battlefield. Its unity, however, is and has been endangered by narratives brought into the centre of national politics by the Italians, who invaded the country in 1935. These narratives place a heavy emphasis on ethnicity, and in particular the differences between the many ethnicities that live in modern-day Ethiopia.

These narratives have played a major role in ethnicising Ethiopian politics and the subsequent Amhara genocide.

Since Abiy Ahmed became Prime Minister of Ethiopia in March 2018, being ethnic Amhara has become a death sentence in many parts of the country. People are constantly killed, evicted, and forced to lead miserable lives for no reason than their Amhara identity. Though the extent of killing and evictions of Amhara escalated after Abiy came to power, it began during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia between 1936 and 1941.

Fascist rhetoric

After being decisively defeated by Emperor Menelik II’s army at Adwa in 1896, the Italians returned to Ethiopia in October 1935 under Benito Mussolini’s leadership. Fascists foment ethnic discord to undermine collective resistance. Knowing that Ethiopian unity defeated them at Adwa, they deconstructed Ethiopian nationhood. The Italians claimed that the state was a mere collection of discrete ethnic groups dominated by Amhara colonial rule. In contrast to Ethiopians’ own notion of mystical unity under the crown of the Emperor, this colonial narrative divided the Ethiopian people into two groups: oppressor and oppressed. The Amhara were singled out as oppressors, while other ethnic groups were regarded as oppressed.

The Fascists targeted the Amhara because the Ethiopian royal family was descended from this ethnic group. The Italian colonisers introduced the discourse of Amhara colonialism into Ethiopian political vocabulary. They claimed Menelik’s territorial expansion in the late nineteenth century was a process of establishing Amhara ethnic domination over other ethnic groups.

What is important about focusing on Menelik’s territorial expansion for the Fascists is that it was through this process that the different peoples of southern Ethiopia incorporated into the centre. Before this expansion, Ethiopia was divided into semi-autonomous principalities due to the decline of the central government, and its subsequent failure to administer all of Ethiopia’s territory. Emperor Menelik undertook the task of reuniting these fragmented territories through both coercion and peaceful means.

This process coincided with the heyday of the European wars of colonisation against other African societies, the so-called “Scramble for Africa”. According to the Fascists, Amhara colonised the diverse peoples of Ethiopia with military and economic support from Europeans. The Fascists argued that non-Amhara populations were then economically exploited and culturally marginalised by the Amhara. They rationalised their presence in Ethiopia by claiming to be liberators freeing the oppressed ethnic groups from the tyranny of Amhara rule. In reality, they deliberately conflated the concept of colonialism with the internal process of state formation to divide and rule the people of Ethiopia.

The politics of today

Despite the eventual defeat of the Italian Fascist invasion, the narratives undermining Ethiopian nationalism remained. In the 1960s, radicalised Ethiopian students embraced the colonial interpretation of Menelik’s territorial expansion. The radicalisation of students was driven by a Leninist understanding of nationality which became popular in Ethiopia during the 1960s. Lenin believed that mankind can achieve the inevitable merging of nations only by passing through the transition period of complete liberation of the oppressed nations.

Students began to view Ethiopia as a ‘prison house of nations, nationalities and peoples’. Walelign Mekonnen – one of the prominent student activists – attacked Ethiopian nationalism, arguing that Ethiopia is not really one nation. Instead, Mekonnen argued, Ethiopia is made of dozens of nationalities with their own languages, ways of dressing, history, social organisation and territorial lands. Borrowing narratives from the Italian colonisers, he concluded that Ethiopian nationalism was propagated by the Amhara ruling class and was a ‘mask’ used by them to oppress other ethnic groups.

Constructing the image of the Amhara as an enemy to inspire political mobilisation, radicalised students established ethnonationalist groups in the 1970s to liberate the designated oppressed ethnic groups from Amhara colonialism. They devised a political strategy that portrayed Amhara as the enemy of the entire non-Amhara population. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) declared that the aim of its struggle was anti-Amhara national oppression, claiming that all forms of injustice in Ethiopia stem from the alleged Amhara ruling system. The overall objective of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) was the realisation of national self-determination for the Oromo people and their liberation from oppression and exploitation perpetrated by the Amhara people.

These ethnonationalist fronts seized power in 1991 by defeating the Derg regime, a Military-Marxist government that had ruled the country for seventeen years. They continued to employ the image of Amhara as the enemy of other ethnic groups to mobilise non-Amhara populations in their own interest even after assuming power. Their rhetoric reduced Amhara to subhuman creatures by excluding them from moral realms and made them suitable for various forms of degrading treatment, such as kidnap, torture, and eviction from their homes.

Government officials spread anti-Amhara propaganda by leveraging their influence over the media and direct access to the public. The culmination of the continuous vilification of Amhara was the instigation of genocide against them. Beginning during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, the scale of the Amhara genocide increased at an alarming rate after ethnonationalist groups seized power in 1991, reaching a crescendo after Abiy assumed office in 2018.

Words have consequences

Hate speech has the capacity to downgrade humans to a sub-human creatures so that genocidal violence is justified by perpetrators. Citing some of the death tolls and evictions of Amhara is valuable to demonstrate the intensity of the problem, but it is difficult to find precise data due to the covert nature of the atrocities.

During the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, between 600,000 and 800,000 Amharas were chased out from various parts of the country. Human Rights Watch reports that around 320,000 Amharas were killed and evicted from Arba Gugu, a tiny province in the Oromia region between 1991 to 2001. The TPLF youth wing known as Samri slaughtered about 1563 Amharas between 6 and 10 November 2020. The Oromo Liberation Army, a breakaway armed wing of the OLF, killed 54 Amharas in Wollega of the Oromia region in an attack instigated on 1 November 2020.

Even as this piece was being written, Amhara have been killed, evicted, and forced to live a miserable life in Wollega. An intervention, be it political or otherwise, is required to stop this persistent inhumane action.

The narratives of Amhara colonialisation unleashed by Italian Fascists on Ethiopia for their own ends have done lasting damage that has long outlived their own attempted colonisation.

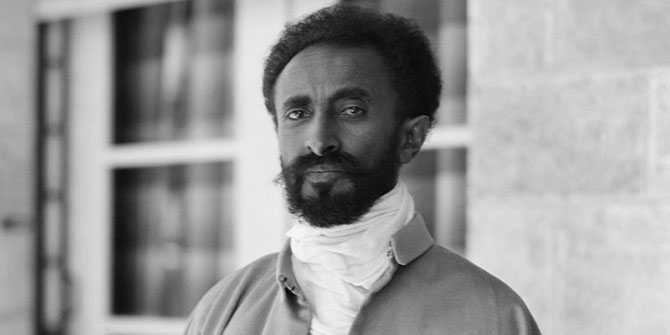

Photo credit: Ninara used with permission CC BY 2.0

This is really interesting article to read, and is indeed new perspective on the subject area. I personally believe that, Ethiopian history and oral tradition needs to be refined and deeply researched to come in to common understanding among nations and reveal the truth behind the driving forces of interethnic conflicts and hate speeches.

Interested, the article reflects the decades-long massacres and enforced disappearances of the Amhara people. Given the ongoing nature of the violence, the actual number is expected to be higher. If you are an Amhara, whether you are a child or an elderly person, able-bodied or disabled, a man or a woman, you will be killed.

This summarizes the hidden and lasting effect of colonialism,

I found it very fascinating dear Bire. Keep up the good work.

Interesting article. There need to be more dialogue in the issue.

Amazing insight, putting the fact to public

Well articulated. Timely,sound and alarming. Keep it up!

This is a good piece of text;it is also impotant you add on decolonizing process for resolving the isue.

Inferiority is a very dangerous disease!! The wonderful and proud patriotic amhara people have founded and defended our beloved ancient Ethiopia 🇪🇹 for millennia!! Without patriotic and brave peoples like the great amharas, our Ethiopia 🇪🇹 would have been colonized just like other African countries! To be inferior and subject to another human being is something I can’t accept at all!!! In summary, every Ethiopian must unite and work together for a united democratic Ethiopia 🇪🇹!!!

Keep up the good work, but Dear Brie please share in detail Amhara peoples are under genocides intentionally

Keep up your good work and documentation of amhara genocide.

I enjoyed this piece very much. Please keep publishing, raising awareness about the Amhara’s predicament.

keep up the good work. As academician a lot is expected from scholars in the area to share the genocide of Amhara innocent people for the international community.

Interesting article . Thanks for your Contribution brother Birhanu.

This is really an interesting article which clearly show how Amhara’s are under the risk of ongoing Genocide. Universities which do researches on Genocide didn’t see #AmharasGenocide or they are not interesting to focus on this issue, Amhara Genocide in Ethiopia. You gave us a wonderful insight. Thanks Man!

Very interesting piece, on a topic that is not very commonly discussed (even in Italy). Lasting consequences of colonial policies should be a key factor in discussing current political situations.

It is also important to keep the balance in order to avoid becoming a nationalist on the other side, becoming what we are criticizing. Hence, it would be interesting to explore how and why the narrative worked so well, lasting for several generations. Most probably, there was a basis of truth about Amhara’s colonialism/imperialism. What other colonial powers (possibly European) supported its regime? How and why?

My dear brother,just l am proud of you.The paper is so amazing and it implies the current core issue about our Amhara people. I hope you will reach on your specific goal.

I am proud of your script may God bless

Very insightful article, thank you for sharing! Despite resisting colonization, Ethiopia is still be afflicted by European colonialism to this day it seems. The Amhara people have been subject to ethnic cleansing for too long. I hope and pray there will be an end to this unjust cruelty. I’m saddened by what is happening but i’m even more proud of those brave Amharas that are defending their people with their lives. May God bless them. Thank you again.

Impresive writing! Bire, keep writing more.

Well articulated and well researched article. Rally great work!