Cecil Rhodes’ policy reforms disenfranchised up to 15,000 mostly black and mixed-race voters in South Africa. This voter suppression created an unequal political environment that favoured white men 50 years before apartheid, write Daniel de Kadt and Joachim Wehner.

On 9 April 2015, a movement of student activists at the University of Cape Town called ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ won a decisive victory with the removal of a statue of Cecil John Rhodes from their campus. This spurred a renewed examination of Rhodes’ legacy in South Africa and beyond. Oriel College at the University of Oxford has faced calls to remove a statue of its former student and benefactor but has so far resisted. The Rhodes Trust, home of the Rhodes Scholarship programme, has undergone a period of retrospection about its founder.

One of Rhodes’ less-understood legacies was his use of ostensibly legal voter suppression techniques to disenfranchise black and coloured voters whose right to vote was legally protected by the Cape Constitution. From 1854 all men, regardless of race, who were aged 21 or older were eligible to vote if they occupied property of a certain value or met a minimum salary restriction.

Voter suppression techniques are now widely used in modern democracies by opportunistic politicians seeking to disenfranchise certain segments of the electorate. Rhodes was an ‘early adopter’ of these tools.

Acts of destruction

Following the eastward expansion of the colony from Cape Town into the modern-day Eastern Cape raised the prospect of the growing number of black voters influencing increasingly competitive electoral races. Rhodes, as Prime Minister, was responsible for drafting and passing the 1892 Cape Franchise and Ballot Act. The new law increased the value of the property of the occupancy qualification and introduced a literacy test. In 1894 he conceived the Glen Grey Act which devised a spatially targeted pattern of landholding for the black population that excluded certain types of property from the occupancy qualification regardless of its value.

The 1892 Act leveraged the racial realities of the Cape’s economy to create racial disenfranchisement. Because black and coloured people were systematically paid less than white people, they rarely qualified based on salary and instead had to rely on the occupancy qualification to gain the franchise. By raising the occupancy qualification (and introducing a literacy test), black and coloured voters were more likely to be denied the vote.

The 1894 act, which Rhodes viewed as a “native act for Africa”, leveraged the spatial geography of different race groups and was applied only to specified districts with a high concentration of black people. This became the backbone of the 1913 Land Act, and the various efforts to create and codify the Bantustans, which were areas set aside specifically for black people to live in.

These acts were deliberately intended to suppress specifically black voters. Socioeconomic and spatial levers became common tools for successive Cape and South African governments until the apartheid government finally extinguished voting rights for all but white people in the mid-1950s. Despite the importance of the 1892 and 1894 laws in South Africa’s history, little is known about their precise impact on the electorate.

The 1903 voter roll from the Cape of Good Hope comprises 135,457 individuals who were registered to vote that year. This was the first time that every voter’s official ‘race distinction’ was also recorded, which enabled the colonial government to monitor the influence of black voters. The 1903 roll also provides information on who was already registered in 1891, prior to the reforms initiated by Rhodes. This allows the number of voters of colour who could have been on the 1903 roll without voter suppression to be calculated.

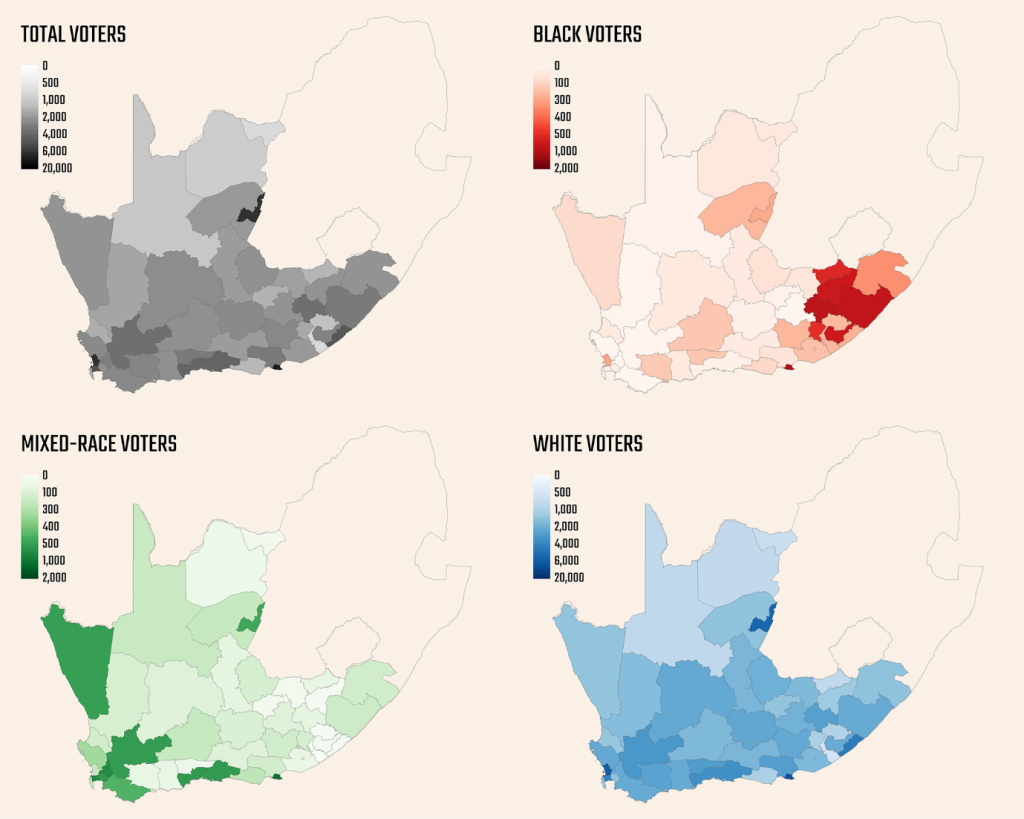

Chart 1 shows the distribution of voters across the 46 electoral divisions in 1903. Rhodes’ franchise reforms increased political inequality between population groups in favour of white men. The magnitude of these effects is striking. Between 10,000 and 15,000 mostly black and mixed-race voters were disenfranchised between 1891 and 1903. Without suppression, the number of voters of colour would have been 50 to 75 per cent higher.

The 1892 Act accounted for the majority of disenfranchisement over this period because it affected the entirety of the Cape. By contrast, the 1894 Act, which was geographically targeted at the modern-day Eastern Cape, was extraordinarily effective at disenfranchising voters, but its effects were more narrowly focused.

Far-reaching impact

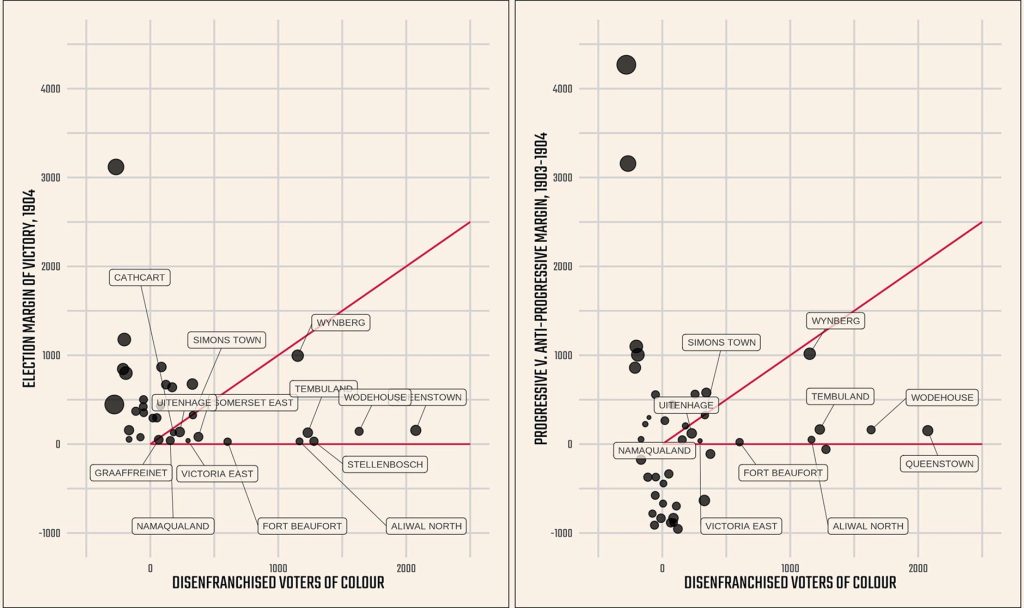

The broader impact of these reforms on South Africa’s political history is hard to overstate. In the 1904 election (for which the 1903 roll was prepared) the number of disenfranchised voters of colour could have been pivotal in 42 per cent of the electoral races that year (see Chart 2). By altering the electorate, these laws potentially changed the outcome of the 1904 election and strengthened nationalist parties. More broadly, the reforms laid the groundwork for the formal establishment of the whites-only franchise over the course of the 20th century.

At the same time, the laws contributed to growing political activism among people of colour. The early experience of political participation and targeted disenfranchisement contributed to black political mobilisation in a unified South Africa. The struggle over the right to vote in this period triggered a response that shaped the history and politics of modern South Africa.

This blog post draws on the authors’ full analysis ‘The Tools of Voter Suppression: Racial Disenfranchisement in the Cape of Good Hope’, which is available open access here. This work was only possible with collaboration from the Laboratory for the Economics of Africa’s Past (LEAP). The entire 1903 voter roll of the Cape of Good Hope has been digitalised and will be available via the LSE Library.