Despite totemic early victories the promise of digital activism to bring about social change across Africa has dwindled and today repressive regimes across the continent have embraced technology for their own ends, writes Dare Leke Idowu.

The global growth in the use of the internet and social media applications for social movements drove the belief among dissidents, scholars and cyber enthusiasts about their efficacy for social change. Enthusiasts of these technologies spoke about their potential to foster democratic reforms and social-economic changes by unsettling autocratic regimes through mass mobilisation of dissenters for demonstrations and online protests like clicktivism, hacktivism, and online polls. Techno-optimists spoke about the prospects of the internet and social media applications creating political and economic opportunities, and opening up contemporary modes of expression.

In Africa, such change has become impractical. Political leaders have combined technology and brute force to frustrate online and offline collective actions. Autocratic leaders have embarked on the retroactive use of old laws and formulated new anti-social media laws to punish dissenters. Regimes have also imported technology and expertise to censor the internet and social media platforms. These actions have quelled dissenting posts, frustrated and prevented online mobilisation for physical protest, and tracked protest organisers and funders. Instead of fostering protest, digital technologies are fostering repression.

The Arab Spring and the surge of digital activism in Africa

It all began so differently. The Arab Spring animated the optimism of using digital technologies as non-violent tools for challenging power in Africa. The mass protests began in Tunisia in 2010, after the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit and vegetable seller.

Inspired by the Tunisian revolution, the Egyptian protesters used Twitter, Facebook, and other digital messaging tools to organise popular protests. After 28 days of incessant protest in Cairo’s Tahir Square, Hosni Mubarak was ousted from power after 23 years of repressive rule.

The failed promises of digital activism in Africa

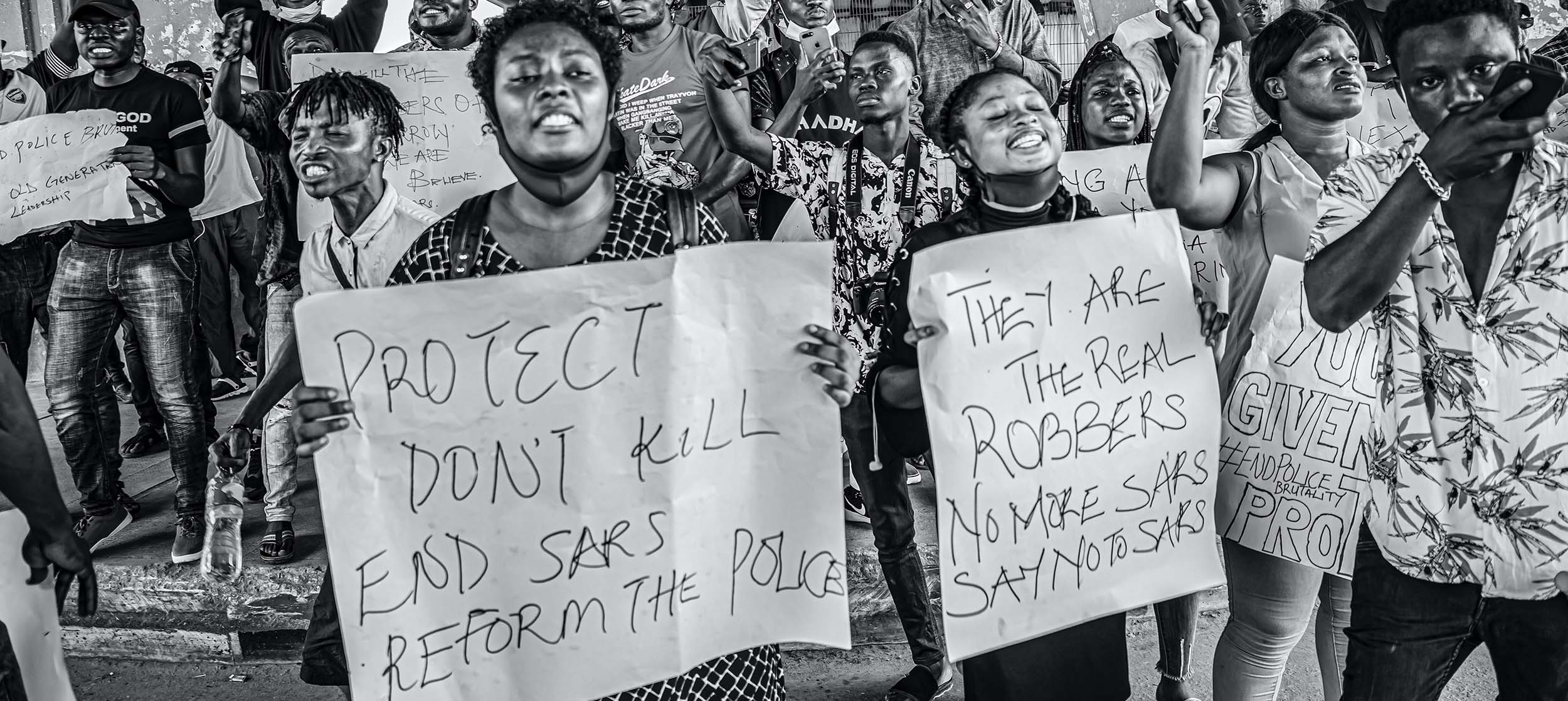

Following the ousting of the Tunisian and Egyptian autocrats, a wave of digital activism quickly spread across Africa. Dissenters and protestors used digital technologies to mobilise and challenge their leaders on issues like economic hardship, political repression, and gender-based violence. Analysis of this digital activism reflects the realities of temporary joy, anguish, and mixed results.

Beyond the ousting of Presidents Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak, change in Tunisia and Egypt was relatively small. Overall, despite the widespread use of new digital technologies, African protestors have only made small gains in the pursuits of political, economic, and institutional reform.

The outcomes of the last decade of digital activism undulate between triumphs, small wins, and relapses into suppression and a more intense constriction of the civic space by African leaders. Although Tunisia embraced reforms amidst high unemployment and socio-economic woes, the government continued to censor the digital space and arrest and detain persons identified as critical voices online. The government revived old laws, introduced new laws to repress the right to free speech, and stifled the civic space with specified penalties for dissidents. Egypt, now governed by the military, regressed deeper into a repressive state that uses digital technologies and state security forces to gag the civic space, constrict political freedoms and violate human rights.

This gap between reality and expectation led many to reflect on the viability of digital technologies to bring about social change in Africa. The governments of Algeria, Zimbabwe, Gabon, and Uganda, have all embarked on periods of blocking internet access and shutting down the internet and social media applications.

In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni blocked access to social media before the 2016 elections and imposed a social media tax to deal with online gossipers and dissenters. Under the guise of protecting people from hate speech and fake news, pro-government parliamentarians introduced bills aimed at consolidating the government’s control of the digital space, but these were eventually defeated.

After Twitter deleted a Tweet by Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, the government banned the use of the social media platform for seven months and arrested the #EndSars protesters.

Although digital activism has remarkable potential for mass mobilisation for collective action, African leaders have themselves used digital technologies and state forces to punish critical voices. What was once regarded as a tool for activism against the state has, in Africa, become a tool through which the state perpetrates repression, censorship, and the shrinking of the civic space.

Digital repression and a gloomy future

African leaders have at different times embraced the idea that Africa’s future lies in embracing digital and emerging technologies to foster development. At the same time, they have demonstrated a strong commitment to banning or censoring citizens’ use of the same technologies.

Following the importation of surveillance technologies and expertise from developed states like China and Russia notable for their poor human rights records, African leaders have become adept at using technologies to perpetrate digital repression using hate speech and fake news as an alibi.

Internet censorship, shutdowns and social media bans now cripple the capability of dissenters to embark on social movements. Africa recorded 19 cases of internet shutdown in 12 countries in 2021 and nine cases in seven countries in 2022. The continent has the record for the longest active internet shutdown -in Tigray, Ethiopia. Since 2015, 30 out of Africa’s 54 countries have imposed restrictions or outright blockage of social media access.

The continued repression of the digital space will frustrate dissenters’ efforts in challenging power and demanding social change in a continent plagued with bad leadership. The initial optimism about the potential of digital activism has, in Africa, met a sad reality.

Photo credit: Hossam el-Hamalawy used with permission CC BY 2.0

What an evocative write-up! African autocratic leaders know that our freedom lies in our speaking out and that is why they continue to stifle us and stop us from protesting on social media. I pray for an Africa that embraces true democracy, civil freedoms and human development.

This is a lovely one !! During the 2020 Beninese municipal election on 17th May 2020 . The president of Benin Republic Patrice Talon ordered for a powerouttage and all telecommunication network were out through the period of the election

This write up really goes into detail about the scope of digital means in the political activities and feedback from public opinion. If Africa can apply and put into practice the true nature of democracy, we will be looking at a positive change in Africa’s affairs

African leaders have increasingly continued to turn access to the internet on and off as they would the light bulb in their living room, all in the name of regulating hate speech and what not. The truth of the matter is that digital activism has become the new voice of the voiceless African who has for so long been burdened under the yoke of corrupt politics and policies and the likes. The future of digital activism is still bleak, but it definitely cannot be business as usual. We must keep demanding more! Thanks for the write up Prof!

Dare Leke Idowu, I agree with the thought process of your writing and the insightful characterization of how digital activism has failed in its promise to deliver social change. On the other hand, digital activism or what is rather called social media activism has delivered common change and aspirations of the masses. Read for example the process of political change in the article writings by Japheth Ondiek and Gedion Onyango on “Social Media and Political Change in Sudan and Ghana”, you will realize how to some extent digital activism plays a vital role in democracy, political mobilization, citizen engagement and acting as watchdog against abuses of power. https://horninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/HORN-Bulletin-Vol-IV-%E2%80%A2-Iss-IV-%E2%80%A2-July-August-2021.pdf. Currently, the drive by digital activism has exposed the corruption rot at the Ministry of Immigration Services in travel passport application and this has forced the government to intervene on behalf of citizens to arrest the cartels who are exchanging services for money. So the arguments entirely depends on the variables against digital activism.