Public disclosure policies are designed to raise tax compliance where alternative enforcement capacity is limited. But they can also have negative consequences by showcasing the true extent of tax compliance, writes Priya Manwaring and Tanner Regan.

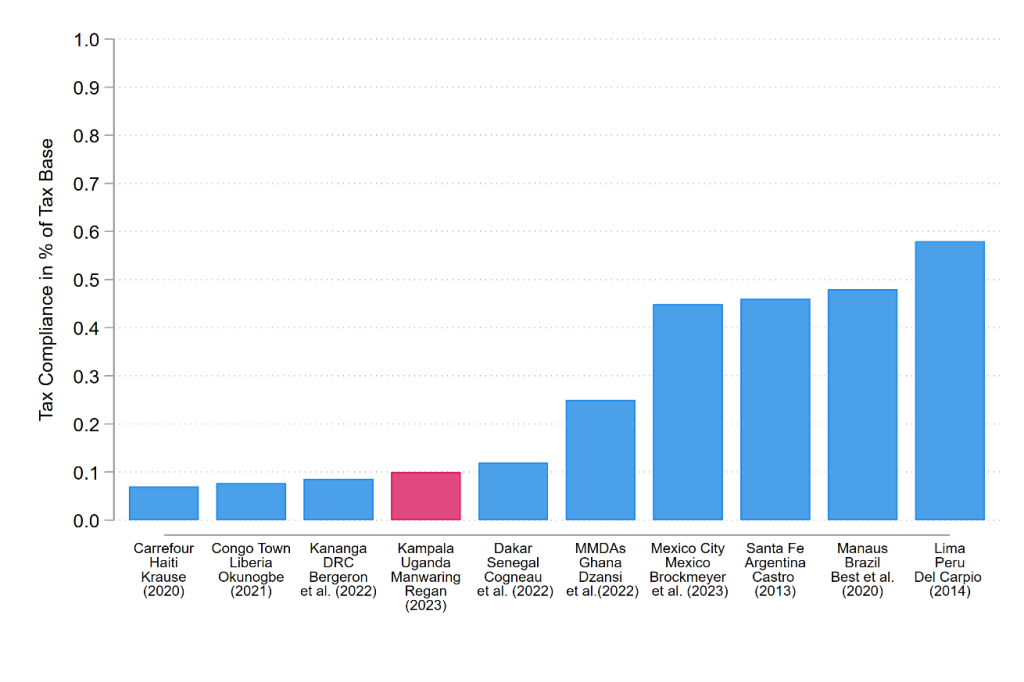

In 2021, property taxes accounted for roughly half of the city government of Kampala’s revenue. But the share of properties paying their annual liability – the compliance rate – has been stuck at roughly 10 per cent for the last 4 years. This is a common challenge for cities in low-income countries as the graph below shows.

Figure 1. Property tax compliance rates across countries

Raising compliance rates is difficult for local governments with limited enforcement capacity. Because of this, many governments are looking to policies that leverage the social aspects of “tax morale” to raise compliance. For instance, if citizens are ashamed of being known as someone who doesn’t pay their taxes, then the government can leverage this by publicising individuals’ tax payments in order to raise compliance. Or, if taxpayers are more motivated to pay taxes when they know that others pay as well, then the government may be able to raise compliance by publicly advertising compliers. These types of public disclosure policies are, according to the OECD, the fourth most used instrument of tax debt enforcement worldwide.

Despite their appeal, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of public disclosure policies at raising tax compliance in low-income countries.

Public disclosure policies and tax compliance

When it comes to publicly reporting tax delinquents, the direct effects are positive. Taxpayers are more likely to comply when they are warned that they will be disclosed as delinquents. But the side effects are negative. Taxpayers are less likely to comply when they receive reports of delinquents. This second fact demonstrates an important unintended consequence of public disclosure policies: that the dissemination of tax delinquency may lower morale more generally.

Surprisingly, the direct effects of recognising compliers are also negative. Taxpayers are less likely to comply when they will be honoured as compliers. It seems that taxpayers neither want to be reported as delinquents nor recognised as compliers.

The results suggest that taxpayers incur a “privacy cost” when being revealed as tax eligible, but no additional “shame cost” from being revealed as non-compliant. There may be a number of factors contributing to this privacy cost, including kin taxes, where extended family and friends solicit the owner for financial favours, and concerns for personal privacy or security.

Another surprising result is that the knock-on effects of recognising compliers are also negative. Taxpayers are less likely to comply when they receive lists of compliant taxpayers. Receiving lists of either delinquents or compliers lowers the respondent’s belief that others in the city tend to pay theirs. This may be because they do not recognise the list of compliers they receive and infer that fewer people are paying their rates than they initially thought. This in turn demotivates – taxpayers are less likely to pay their taxes when they believe that more taxpayers are delinquent.

These results together provide a policy-relevant basis for understanding the effects of public disclosure on tax payments in low-capacity, low-compliance settings. The effect of public recognition in this context is negative. For public disclosure of delinquency, the positive direct effect could outweigh the negative knock-on effect. But public disclosure seems ineffective when compared to a simple reminder message that tells taxpayers the actions that government can take against delinquents: we find that this type of message is at least as effective as the threat of public reporting, without its negative knock-on effects.

This article is based on CEP Discussion Paper 1937 ‘Public disclosure and tax compliance: evidence from Uganda’

Photo credit: Michell Zappa used with permission CC BY-SA 2.0