Faith organisations can be a vital ally for governments in public health policy. But they need to understand how these groups understand disease to utilise this opportunity, write Emma Wild-Wood and Yossa Way.

Faith communities provide support and resilience for large sections of society and so working with them during a health crisis is vital. Yet faith leaders in north-eastern Congo said that they were overlooked by government organisations during the Covid-19 pandemic. Understanding the range of perceptions of disease and health within faith communities is a first step towards better collaboration.

International humanitarian groups increasingly recognise the social capital of faith communities in Africa. However, they often approach faith communities in a reductionist and instrumentalist manner, rather than attempting to understand them from within. This western approach is replicated by governments and ministries of health across Africa. Frameworks developed to address Covid-19 rarely mentioned faith communities and the few that did usually limited their role to community mobilisation.

Faith communities have diverse histories, beliefs, and practices. They have different relationships to the state and different attitudes towards health. Identifying this diversity is crucial. In D.R. Congo, Christianity is the largest religious group, with a minority of Muslims and indigenous religious adherents. The Roman Catholic Church is the largest church with a significant health delivery infrastructure supported by its humanitarian organisation Caritas Congo. It took a prominent role in the public health response to Covid-19. Some Protestant and Pentecostal Churches also supported the government’s public health measures, while other Pentecostal and independent churches placed an emphasis on faith healing.

Faith healers often believe that medical practices can cure some diseases but not all. Christian faith healers diagnose illness emanating from ancestors, spirits, and witchcraft. They are likely to exorcise ancestors and spirits to achieve wellness for the sick. Indigenous religious healers are likely to identify illness and misfortune arising from the neglect of ancestors or spirits, sometimes caused by social discord and prescribe certain practices and herbs as remedies.

Members of faith communities held different views about the diagnosis of Covid-19 and best response to it. They fell into four broad categories:

Covid-19 is a ‘natural’ disease, caused by the transmission of a virus. It requires prayer, biomedical and public health approaches to overcome it.

Covid-19 is a supernatural disease, caused by the devil, malign spirits or God. It requires only spiritual intervention through prayer, faith-healing practices, and exorcism to overcome it.

Covid-19 is a fabricated disease. It is fictitious, in which case it can be ignored, or it is man-made, in which case either public health measures or faith healing may be good responses.

Covid-19’s existence or nature is unclear, respondents were confused by the information available and unsure how to respond.

Whether Covid-19 was perceived as having a primary ‘spiritual’ or a ‘natural’ cause or was ‘fabricated’ influenced the level of compliance to public health measures introduced by the government from March 2020. The extent to which people were ‘unsure’ about Covid-19 influenced how regular or consistent they were in their actions in response to the disease. The number of recorded cases of Covid-19 also changed perceptions. When cases of COVID-19 were low, many speculated that the disease did not exist or considered it was a western disease. They were less likely to alter their behaviour significantly. When cases began to rise, particularly with the advent of the delta variant from June 2021, pragmatic responses to protection against the disease superseded speculation about the nature of the disease.

Members of faith communities have some similarities in their understanding of Covid-19. They all considered that evoking the spiritual or supernatural in some way was essential for well-being in the face of disease. There was a shared expectations of the therapeutic power of prayer to combat disease and to fortify the faithful in the face of adversity.

In Ituri and Nord-Kivu regions of DR Congo, there was a wide-spread preference for in-person, collective religious events which meant that the closure of churches caused distress among all groups. In most cases, there was dismay at government instructions that appeared to overlook the appeal to powerful spiritual beings in the face of disease. The dislike of public measures was often magnified by the inability of the state to bring peace to a region of conflict and criticism about the handling of the Ebola outbreak 2019-2020.

The understanding that Covid-19 was a natural disease was likely to encourage faith communities to comply with public health advice from the provincial governors’ offices. For them, prayer remained important alongside public health measures as a way of tackling the disease. They could countenance building closure as a temporary measure and considered that prayer in households, small groups or via the radio was ethically considerate and equally effective that in religious buildings.

The view that Covid-19 is a supernatural disease and only required a spiritual response was more likely to come from members of Independent Churches, Pentecostal Churches and indigenous religious communities, but it was certainly not limited to them. They were likely to consider the government public health advice as misguided or negligent because it prevented the very activities that would address the problem. The banning of collective worship prevented corporate faith healing or exorcism of evil spirits. Thus, in their view, a mechanism for combating Covid-19 was prohibited by a government who failed to understand the spiritual origins of the disease.

Faith communities offer individual and community resilience in Congo through spiritual beliefs and practices and through the mutual care of members. Faith leaders disliked the apparent subordination of faith to the imperatives of health care.

The plurality of views about Covid-19 expressed in faith communities raises important questions for public health interventions. This is particularly the case for those communities whose beliefs and practices contradict the health measures implemented to reduce disease. The differences are important because they may influence future civic engagement and relationship to governance.

Recognising the reasons why these communities are trusted by their members and provide them with societal resilience in the face of multiple challenges will help facilitate a more responsive approach during the outbreak of diseases in the future.

The Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK [RA5023] funded the research.

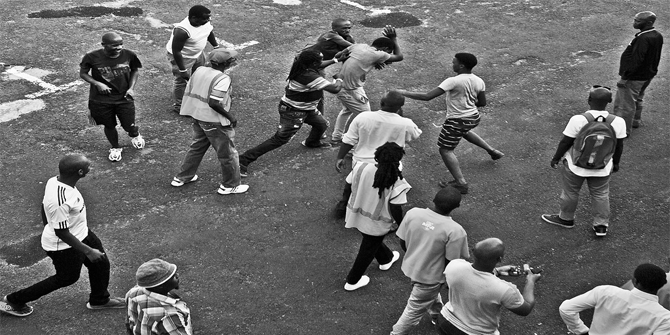

Photo credits: Main image Kevin Walsh used with permission CC BY 2.0 and Yossa Way used with permission.

Thank you Emma and Yossa, I thoroughly enjoyed your article. I have been researching the role of religious leaders in health since 2014. Here are some of my recent publications. I am also working on the book on relationship of health NGOs and religious leaders in Tanzania.

1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953621009825

2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36228080/

I would love to hear your thoughts.

As always, Yossa and Emma, Your article was very interesting to me. Since 2014, I have been investigating religious authorities’ impact on health. Some of my most recent articles are shown below. I’m also writing a book about the interaction between health NGOs and Tanzania’s religious authorities.

Be careful, this game can be addictive.